- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

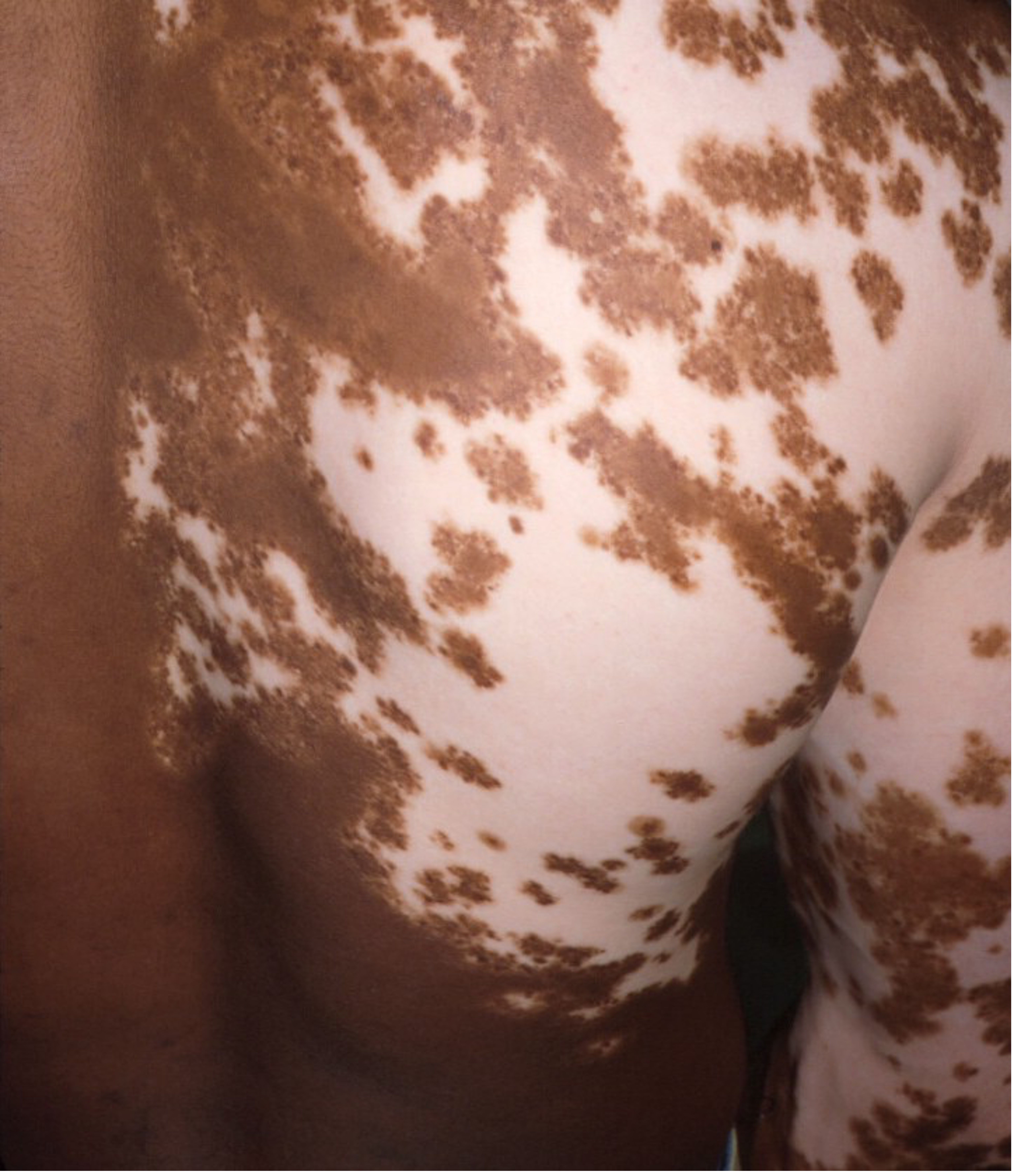

A Case of Vitiligo in an 11-Year-Old Male

Author(s):

A case study reviewed an 11-year-old male for loss of pigmentation of the right side of his back and right arm.

Case:

You are asked to evaluate an 11-year-old male for loss of pigment on the right side of his back and right arm. He is an otherwise healthy young boy, with no personal history of dermatologic disease, though he does have an uncle with vitiligo.

Case image

Diagnosis and Pathogenesis: Vitiligo.

Vitiligo is an autoimmune dermatologic disease in which epidermal melanocytes lose their function causing depigmentation of the skin, presenting as well-demarcated white macules and patches on the body.1 The condition is estimated to impact 1% of the population world-wide. The exact pathogenesis is unknown, though it was hypothesized that a combination of genetic, immunological, neurogenic, and environmental factors are at play. It is often associated with other autoimmune diseases. The condition often arises in childhood, making early detection and intervention essential. Traditionally, vitiligo initially presents on the hands, forearms, feet, and face, often in a perioral or periocular distribution.1 The disease course is rather unpredictable, but tends to continue to spread centrifugally, ultimately involving more of the total body surface area.

Psychosocial impact:

Though an asymptomatic condition, vitiligo is often considered disfiguring, making it a source of extreme psychosocial stress for patients, especially pediatric patients and their parents.2 The disease is also more obvious in patients with skin of color, making these patients more susceptible to the distressing nature of the disease. Vitiligo can be socially and culturally stigmatizing therefore impacting the quality of life for patients of all ages and skin tones.2 Depression, stress, and low self-esteem are commonly encountered comorbidities among vitiligo patients.Psychological therapies and support may be necessary adjunctive therapies in the management and treatment of psychosocially distressing skin conditions like vitiligo.2,3

Traditional and new treatment options:

Treatment of vitiligo is difficult given that the disease course is often unpredictable and has variable responses to treatment. Thus, treatment typically requires multiple modalities to elicit a response and should be individualized to meet the needs of each patient. The two major goals of treatment are to halt active disease and induce repigmentation.4 Traditionally, topical steroids, oral steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phototherapy with narrow-band UVB are considered the first-line therapeutic options, given their safety and efficacy. Other therapies include photochemotherapy, lasers, antioxidants, topical Vitamin D analogs like calcipotriene, prostaglandin analogs like bimatoprost, and surgical skin grafting.4,5 Systemic medications like the alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogue afamelanotide, minocycline, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine, L-phenylalanine, khellin, and a number of supplements have been used with varying success.4Over the last decade, substantial research and progress has been made in the treatment options for vitiligo. Janus Kinase (JAK) inhibitors like tofacitinib and ruxolitinib, are an emerging therapy used to treat a number of dermatologic conditions, including vitiligo. In fact, the evidence supporting the safety and tolerability of topical ruxolitinib was substantial enough to gain recent FDA-approval for the treatment of vitiligo in patients ages 12 and up.4 Other JAK inhibitors show good efficacy, though they lack the randomized control trials to fully substantiate their therapeutic effect, making this a necessary future area of study.4,5 Finally, if substantial body surface area is involved and disease is recalcitrant, efforts can be made to depigment the remaining skin that still have pigment with agents like the recently FDA-approved monobenzylether of hydroquinone (MBEH) to achieve homogeneity of the skin complexion.4

References:

- Ahmed jan N, Masood S. Vitiligo. 2022 May 8. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. PMID: 32644575.

- Picardo M, Huggins RH, Jones H, Marino R, Ogunsola M, Seneschal J. The humanistic burden of vitiligo: a systematic literature review of quality-of-life outcomes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022 Sep;36(9):1507-1523. doi: 10.1111/jdv.18129. Epub 2022 May 11. PMID: 35366355.

- Rafidi B, Kondapi K, Beestrum M, Basra S, Lio P. Psychological Therapies and Mind-Body Techniques in the Management of Dermatologic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022 Aug 9. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00714-y. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35945404.

- White C, Miller R. A Literature Review Investigating the Use of Topical Janus Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Vitiligo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022 Apr;15(4):20-25. PMID: 35465035; PMCID: PMC9017670.

- Karagaiah P, Schwartz RA, Lotti T, Wollina U, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Biologic and targeted therapeutics in vitiligo. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 Jan 13. doi: 10.1111/jocd.14770. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35029034.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.