- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Advances in understanding, treating MCC

Outcomes for patients with Merkel Cell Carcinoma are typically poor and therapeutic options are limited, but advances in understanding the biology of the disease, as well as emerging cutting-edge treatments are expected to improve the outlook, experts say.

For patients with Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), outcomes are typically poor and therapeutic options are limited, but advances in understanding MCC’s biology and in the emergence of cutting-edge treatments are expected to improve the outlook in this tumor type, according to speakers at the 3rd Annual World Cutaneous Malignancies Congress (San Francisco, 2014).

Evolving understanding of polyomavirus role

Isaac Brownell, M.D., Ph.D., head of the cutaneous development and carcinogenesis section at the National Cancer Institute, described exciting work being done in understanding the polyomavirus (MCPyV) in MCC.

At least 10% of all cancers are driven by viruses, and in 2008 MCC joined this list when approximately 80% of MCC tumors were found to harbor the MCPyV. According to Dr. Brownell, genes in the polyomavirus family express T antigens that allow the virus to co-opt the machinery of the cell, make new viral DNA, and potentially cause cancers.

“We thought we had this nailed down, that MCPyV infection equals MCC, but it’s not that simple,” he says.

Most MCPyV infections are subclinical and not oncogenic, and most adults have circulating antibodies that indicate prior infection. For cancer to develop, however, two other things must occur: Virus DNA must become integrated into the genome of the tumor, and a mutation in the large T antigen must make the virus replication deficient. Interaction with the immune system seals the deal when the host has a loss of protective immunity, for example, because of advanced age. This potentially allows the virus to expand, integrate, mutate, and spur the uncontrolled growth of the tumor, he explains.

RELATED: New medical therapies result in symptoms of various skin conditions

While 80% of tumors are virus-positive, the prognostic implications of MCPyV status remain “questionable,” he says. Some studies have found that virus-positive tumors fare better than negative ones, but other studies have contradicted this.

“The jury is still out on this,” he notes. It is not necessary, therefore, to test for the presence of the virus.

On the other hand, a serological assay for antibodies against the small T antigen of MCPyV could help detect recurrence and allow for prompt treatment of progressive disease. Up to 50% of newly diagnosed MCC patients have antibodies that recognize the T-antigen, but such oncoprotein antibodies are virtually never present in healthy individuals - despite the fact that most people harbor the virus on their skin. Titers are stable or reduced in MCC patients after treatment, but they increase by 20% or more in patients who progress.

The determination of MCPyV status may also, someday, become relevant in terms of treatment. About half of MCC patients have circulating T-cells that are MCPyV-reactive. This could be leveraged for autologous T-cell therapy.

NEXT: New serologic assay

New serologic assay

The “small T serology test” was further described at the meeting by Paul Nghiem, M.D., Ph.D., the Michael Piepkorn Endowed Chair in Dermatology Research at the University of Washington, Seattle, where the assay is available as a “send out test” for around $200 (plus local lab fees).

The small T serology test detects the body’s response to cancer-associated protein, and indicates when cancer has returned since small T-antigen titers are high at diagnosis, drop dramatically with treatment, and rise again upon recurrence. Dr. Nghiem’s data (unpublished) indicate that, after the second blood draw, recurrence-free survival is approximately 90% at two years for patients whose titers continue to fall, 80% for those with stable titers, and 40% for those with increasing titers (P = 0.0003).

Dr. Nghiem recommends that clinicians check serology within three months of diagnosis to determine if the patient is an “antibody producer.” If so, that patient can be monitored via the assay; other patients can be tracked clinically and radiologically. Patients found to be MCPyV-positive and making T cells against the virus could be enrolled on an autologous T cell therapy trial, he says.

Update to NCCN guidelines

The guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) were recently updated to reflect trends in the care of MCC patients, especially those with early stage disease. These updates were described at the meeting by Christopher K. Bichakjian, M.D., associate professor and director of the multidisciplinary MCC program at the University of Michigan, who chairs the NCCN committee on non-melanoma skin cancers.

The Committee referenced the growing interest in MCPyV, noting, “The value of baseline MCPyV serology for prognostic significance and to track disease recurrence is being evaluated,” though no recommendations were made. Dr. Bichakjian says, “This is a development that may prove to be a prognostic tool and to supplement or replace routine imaging in the future.”

Most of the revisions were for the primary treatment of clinically node-negative patients, and for the performance of sentinel lymph node biopsy. The new guidelines:

Provide clear conceptual separation of the management of primary site and regional nodal basin in relation to surgery and radiation therapy.

Encourage observation of the nodal basin in sentinel lymph node-negative patients

Discourage morbid resection for extensive disease in favor of adjuvant radiation therapy

Suggest the clinician consider observation only of the primary tumor bed in low-risk patients after surgery

Dr. Bichakjian notes that while radiation therapy to the primary site can provide a measure of protection to patients with high-risk tumors, he maintains, “There is a sizable group of patients we can probably cure with surgery alone.”

NEXT: Immunotherapy an emerging treatment option

Immunotherapy an emerging treatment option

With current treatment options, outcomes are dismal for patients with advanced disease. Five-year survival is less than 20% when patients present with metastatic disease, according to Shailender Bhatia, M.D., of the University of Washington/Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle.

While MCC is a chemotherapy-sensitive cancer, progression usually occurs within three months and second-line chemotherapy is rarely effective.

“Chemotherapy works well but not for long. Maybe things will change with advances in genetic sequencing,” he suggests; although while several targets have been proposed, there are “no real leads” and “no pathway yet to blame” in MCC.

RELATED: Immunotherapy promising for advanced melanoma

Adjuvant chemotherapy is commonly employed for stage 3 MCC. However, data regarding its effectiveness is limited. Dr. Bhatia’s recent analysis of the National Cancer Database showed no survival benefit associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in stage 3 MCC.[1] Prospective studies are needed to address this important unmet need in patients with high risk of systemic recurrence after surgery and/or radiation therapy.

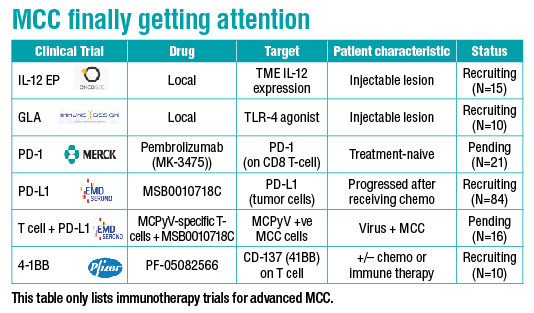

However, the promise of immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma has fueled research in MCC as well. Trials of antibody-mediated blockade of the programmed death 1 protein (PD-1) and its ligand (PD-L1), as well as autologous T-cell therapy, are now enrolling (See Table, page 44).

Dr. Brownell expanded the discussion of immunotherapy for MCC, noting, “MCC is a good candidate for immunotherapy” for the following reasons:

Higher incidence and worse prognosis seen in immunocompromised populations

Improved prognosis observed when patients have CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)

Spontaneous regression occurs

Patients can respond to dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB), tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and interferon

80% express MCPyV viral T-antigens, and patients make virus-reactive T-cells

Improved prognosis observed in patients with high MCPyV titers

Autologous T-cell therapy is an active area of research at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Candidates are patients whose tumors are positive for the virus, and who have virus-reactive circulating T-cells. Researchers collect peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the patient, select the MCPyV-reactive T-cells, expand the CD8+ T-cells, and reintroduce them along with cytokines to rev up the T-cells to attack the tumor. In future studies, they will add immune checkpoint blockade.

RELATED: Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: Poised for a new treatment paradigm

Researchers in Seattle and elsewhere are also evaluating local injections of immunotherapies, including interleukin-12 plasmid with in vivo electroporation, and the toll-like receptor (TLR4) agonist glucopyranosyl lipid. Other research efforts are evaluating checkpoint inhibitor ipilimumab after excision, the addition of the F16-IL2 antibody-cytokine fusion protein to paclitaxel, the efficacy of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors pazopanib and cabozantinib, and, since MCC is a neuroendocrine tumor, the targeting of the somatostatin receptor with various analogues.

Sometimes the goal may be to “buy time” for the patient entering one of these trials, or to simply palliate a bulky tumor. For this, Dr. Bhatia notes success with single-fraction radiotherapy.

“Single-fraction high-dose (8-Gy) radiation therapy is feasible, even at difficult visceral sites. It works well for palliation, with minimal toxicity, even in sensitive organs,” he said. “Most tumors respond, many completely, and many responses are durable. We think this has the potential to act as an in situ vaccine and to work synergistically with other immunotherapies.”

[1] Bhatia S et al. ASCO 2014. Abstract 9014

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.