- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Better understanding of AD portends better treatment

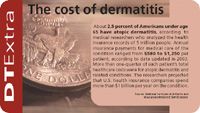

Vancouver, British Columbia — Atopic dermatitis (AD) is on the rise around the world and affects 10 percent to 20 percent of children. The disease may continue into adulthood and may be the first step in an "atopic marathon" that leads to asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Vancouver, British Columbia - Atopic dermatitis (AD) is on the rise around the world and affects 10 percent to 20 percent of children. The disease may continue into adulthood and may be the first step in an "atopic marathon" that leads to asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Dr. Lugar cites a study from Allergy (Gustafsson D et al. Allergy 2000;55: 240-245) which showed that when children suffered from AD, their risk of developing asthma and allergic rhinitis increased in proportion to the severity of their atopic eczema condition.

In atopic eczema patients, the non-lesional skin exhibits a number of specific changes. The epidermis shows traces of hyperkeratosis, hyperplasia and intercellular edema. There is a thickening of the basement membrane, and a dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, endothelial cell enlargement and dilated lymphatics are typically found in the dermis.

Those changes may be signs of either subclinical disease or of a previous episode.

Dr. Luger says evidence is mounting that the pathogenesis of AD may be largely a result of interaction between newly identified chemokines with T cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils and mast cells.

Two distinct dendritic cell populations appear in atopic dermatitis: Langerhans cells (LC) and inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (IDEC) which lead to different T-cell responses.

"In acute atopic dermatitis Langerhans cells primarily give rise to a T2 immune response and mast cells are degranulated, whereas in chronic AD, inflammatory dendritic cells appear sto be responsible for the switch to T1 and mast cells are increased."

"Mast cell tryptase may activate proteinase-activated receptors (PARs), which can cause neurogenic inflammation, recruitment of eosinophils, monocytes and pruritogenic mediators."

As a result, persistent inflammation leads to scratching which results in mast cell and bacterial proteases - along with environmental allergens they can lead to pruritus and more inflammation.

Recent research indicates there may be a functional interaction between the nervous system and the immune system. It appears to be the result of an imbalance of specific neuropeptides and nerve growth factor in inflamed skin.

Dr. Lugar says, "This may also explain the frequently observed stress dependency of atopic dermatitis."

Also, Dr. Lugar says that susceptibility to skin infections and staphylococcal aureus may occur because of a deficiency in antimicrobial peptides in the keratinized layer of the epidermis.

He says the research is giving doctors a better understanding of the complex pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis and that is good news for patients.

"The increasing understanding of the pathophysiology of AD is allowing us to distinguish allergic and non-allergic subtypes of the disease. Ultimately, it will allow for the development of novel therapeutic strategies."

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.