- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Clinical photography dos and don'ts

Author(s):

The need for clear images of cutaneous conditions is more critical in dermatology than perhaps any other specialty. In this article, we feature the photography of Dr. Justin Finch who leads the clinical photography program in dermatology at the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, Conn. Dr. Finch shares his photography tips in this “How To” guide.

The need for clear images of cutaneous conditions is more critical in dermatology than perhaps any other specialty.

A clinical image can mean the difference between a correct diagnosis and clinical error, especially in the age of teledermatology. But taking a good clear clinical image isn’t always straightforward, says Justin Finch, M.D., a dermatologic and cosmetic surgeon with the University of Connecticut Health Center in Farmington, Conn., where he serves as director of clinical photography in dermatology.

Dr. Finch

“In my practice I have 12 minutes to see a patient, render a diagnosis, take pictures, write a note and move on to the next patient. If photography is not quick and easy, I don’t do it, but you can still take quality photos,” he said.

Developing core skills in photography will not only improve the quality of your clinical images, but it could also empower you with the skills necessary to critique less than ideal photos from medical literature or other published materials.

1) CONSENT FORMS

The patient should sign a consent form for photos due to be used - or have the potential to be used - for a second opinion, teaching, education or publication. But legal opinions differ for photos intended only for medical care. In Dr. Finch’s practice, photographs intended only for direct clinical care are covered by consent-to-treat forms patients sign prior to receiving care.

2) TRIPOD

When an image is intended for print publication, use a tripod if it’s Dr. Finch practical to do so, recommend Dermatology Times editors.

3) HIGH DEFINITION

Photos intended for publication must be taken in high definition (300 dpi).

See the related story: "Legal perspectives on using photography in your office"

4) USE A PLAIN AND SIMPLE BACKDROP

This photo demonstrates a case of neurocutaneous sarcoidosis with hypopigmented plaques and facial palsy. A solid blue backdrop was used to avoid distracting background elements. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Finch)

5) AVOID OVERHEAD LIGHTS

To capture the texture of scaly or papular eruptions, such as lichenified skin, turn off the overhead lights and instead, use operating-room lights, pointed at an angle to accentuate textural irregularities.

The image on the left demonstrates the poor use of front lighting for a case of linear IgA bullous dermatosis. The lighting obscures the crown of jewels sign that is characteristic of this condition. The image on the right demonstrates the importance of tangential lighting (side lighting) to accentuate surface texture in the same case of linear IgA bullous dermatosis. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Finch)

Lighting from different angles

This photo demonstrates the use of soft-side lighting to accentuate the scaly surface texture in a case of pediatric polycyclic tinea corporis (ringworm). (Photo courtesy of Dr. Finch)

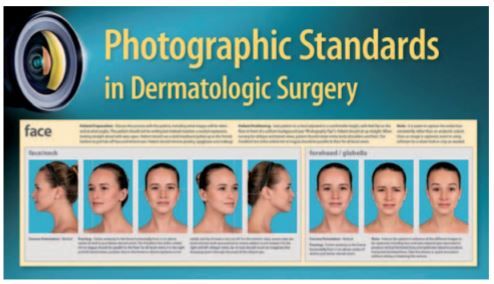

6) STANDARDIZATION

Take the same facial views: Frontal, two lateral and two oblique. Keep the tip of the nose confi ned within the profi le of the cheek. Take the photo the same way each time to facilitate comparisons.

7) FIDGETY PATIENTS

When photographing patients who have difficulty keeping still, use a fast shutter speed of at least 1/250 of a second. And consider using a flash, which is especially helpful when photographing children. The following two photos illustrate the importance of using a fl ash to prevent motion blur in photographing children. The photo on the left was taken without fl ash. It is blurry because the child moved when the photo was taken. The photo on the right shows a crisp, in-focus photo taken using a camera fl ash. While using a camera fl ash typically obscures surface textural detail, in this situation, it was worth the trade-off in order to achieve a crisp image. (Photos: These two images are courtesy of Hanspaul Makkar, M.D.)

8) USE A MACRO CAMERA LENS

A macro lens is a must for capturing details close-up. Some of the non-macro zoom lenses can’t focus closer than 24 inches from the camera. You usually need to get closer to the patient for a good image, says Dr. Justin Finch.

This image demonstrates a case of filiform wart on the neck. Close-up images of details like this are only possible with a macro lens. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Justin Finch)

9) DIGITAL ADJUSTMENTS

Some photos benefi t from post-processing digital adjustments to enhance the detail. Altering contrast or color across an entire image is acceptable if it helps viewers interpret the photo, but painting over individual pixels goes too far.

10) CHEAT SHEETS

Hang resources, such as the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery patient positioning poster, in exam rooms where staff members can refer to them when taking photos.

Web screenshot taken from www.asds.net/photostandards.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.