- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Disseminated Erythema Migrans as a Result of Lyme Disease

Author(s):

A 17-year-old male patient presents with multiple lesions developed on his trunk, face, and extremities that had previously been solitary, red expanding lesion on his right arm at the site of a tick bite that occurred during a hike.

The case

You are asked to evaluate a healthy 17-year-old boy who developed a fever, sore throat, and malaise several days after removing a tick from his right arm after a hike in the woods. He noted a solitary, red expanding lesion on his right arm at the site of the tick bite. Three days later, multiple lesions developed on his trunk, face, and extremities (Figure). He takes no medications and has no personal or family history of skin disorders.

Figure A

Figure B

Diagnosis: Disseminated erythema migrans as a result of Lyme disease

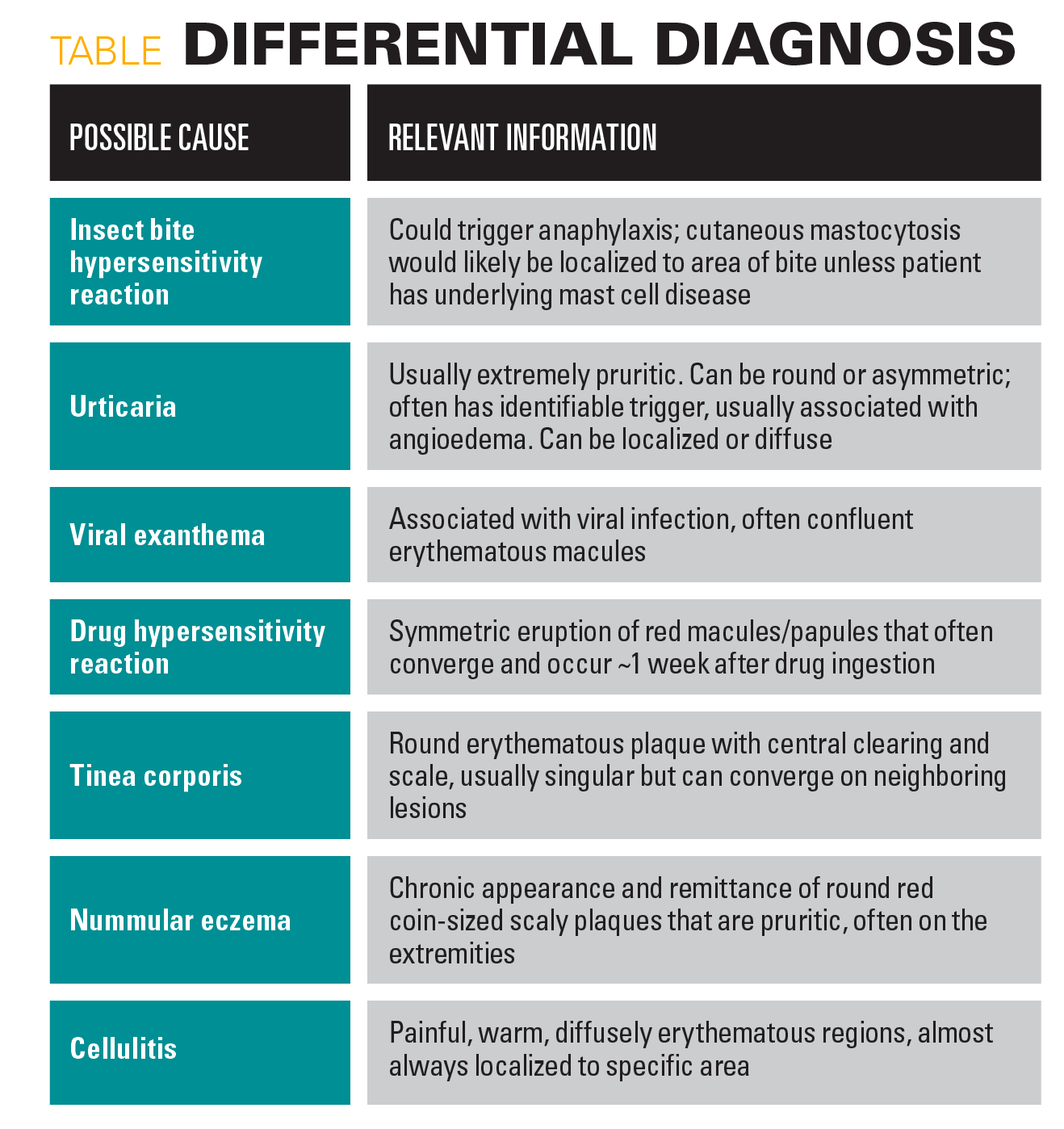

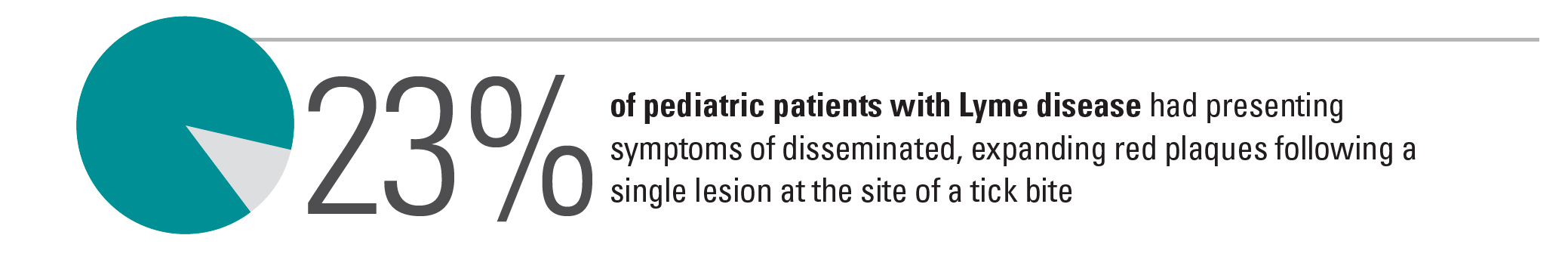

Disseminated, expanding, annular, red plaques with central clearings following a single lesion at the site of a tick bite are strongly indicative of Lyme disease. A singular targetoid lesion is the presenting symptom in 89% of pediatric patients (23% of whom develop multiple lesions).1 These skin manifestations are often associated with systemic symptoms including fever, malaise, and arthralgia; if left untreated, they can progress to include cranial nerve palsy, arthritis, meningitis, or carditis.2 In early localized disease, as seen in this patient, serological studies of immunoglobulin G for Borrelia burgdorferi are often negative, as the body has not had sufficient time to build an adaptive immunological response (ie, less than 3 weeks since infection).3 There are also tests available to detect immunoglobin M antibodies against B burgdorferi, which can be indicative of active infection; however, only 20% to 40% of patients with active Lyme disease will be seropositive.4,5 It can be more clinically useful to observe the rapid clearing of the “bull’s eye” rash and associated symptoms (within 1-2 days of starting antibiotic therapy) to confirm the diagnosis of Lyme disease in an endemic area, especially if the patient has a history of tick exposure.

Table

Treatment

Although several antibiotics have been shown to be effective in treating early Lyme disease, doxycycline is usually recommended due to its efficacy in treating possible coinfections.6 Other antibiotic options, which are usually preferred for pregnant women and children aged younger than 8 years, include amoxicillin and cefuroxime axetil.

Our patient

This patient started on oral doxycycline, and 36 to 48 hours after starting the antibiotic, he reported feeling much better; his skin rash had almost completely resolved. He completed 3 weeks of oral antibiotic therapy and experienced complete resolution of symptoms without lasting pigmentation changes or scarring. Most patients with acute Lyme disease recover completely within 20 days of onset.7

This article originally appeared in our sister publication Contemporary Pediatrics.

References:

1. Gerber MA, Shapiro ED, Burke GS, Parcells VJ, Bell GL. Lyme disease in children in southeastern Connecticut. Pediatric Lyme Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(17):1270-1274. doi:10.1056/NEJM199610243351703

2. Applegren ND, Kraus CK. Lyme disease: Emergency department considerations. J Emerg Med. 2017;52(6):815-824. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.01.022

3. Tugwell P, Dennis DT, Weinstein A, et al. Laboratory evaluation in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12):1109-1123. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00011

4. Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Forseter G, et al. The clinical spectrum of early Lyme borreliosis in patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. Am J Med. 1996;100(5):502-508. doi:10.1016/s0002-9343(95)99915-9

5. Nowakowski J, Schwartz I, Liveris D, et al; Lyme Disease Study Group. Laboratory diagnostic techniques for patients with early Lyme disease associated with erythema migrans: a comparison of different techniques. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(12):2023-2027. doi:10.1086/324490

6. Wormser GP, Nadelman RB, Dattwyler RJ, et al. Practice guidelines for the treatment of Lyme disease: The Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(suppl 1):1-14. doi:10.1086/314053

7. Luft BJ, Dattwyler RJ, Johnson RC, et al. Azithromycin compared with amoxicillin in the treatment of erythema migrans: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(9):785-791. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-124-9-199605010-00002

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.