- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Louisville face transplant team weighs psychological concerns,potential risks

Louisville, Ky. - Before submitting an Institutional ReviewBoard (IRB) proposal in the United States to perform what likelywill be one of the world's first face transplants, researchers hereare addressing a host of ethical and practical matters they hopewill smooth the approval process.

"Our approach differs from most surgical clinical research," says John H. Barker, M.D., Ph.D., director of plastic surgery research at the University of Louisville and coordinator of the university's face transplant team. Usually, he explains, "First we do it, and if it worked, then we tell the world."

In contrast, he says that because of the intense media interest in the project, his multidisciplinary team - which includes psychologists and philosophers along with surgeons - first floated its IRB proposal in public and in other forums, requesting critiques from professionals and peers (Wiggins OP, et al. Am J Bioeth. 2004 Summer;4(3):1-12). Should any critique persuade researchers they shouldn't proceed with face transplantation, he adds, "We won't do it."

"If the face transplant fails," according to Arthur Caplan, Ph.D., "the patient probably will beg for (euthanasia). How researchers are going to manage that, I've not seen in either protocol (see related article). If there's a rejection, either acute or chronic, there's nothing else one can do to go back, which will leave the patient unable to eat or breathe." He is chairman of the department of medical ethics at the University of Pennsylvania.

If transplant fails

"Several (experts) have said if one has to remove that face, the patient will die," Dr. Barker tells Dermatology Times. "That's not true," he says, adding that should an exit strategy be required, researchers will remove the tissue and find another donor to replace it, depending on the reason for the rejection. If that fails, he says, "Then we will revert to the conventional reconstructive methods that the patient was already involved in. And because of that critique, we specifically changed our selection criteria" to focus on patients whose disfigurement occurred only one or two years ago rather than those who have already undergone hundreds of reconstructive procedures.

Questionnaire

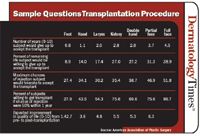

Additionally, the university has administered a detailed and validated questionnaire called the Louisville Instrument for Transplantation (LIFT) to more than 300 respondents including amputees and facially disfigured patients, along with physicians who treat them. It attempts to assess the risk individuals would accept for a face transplant.

"Regardless of which population one asks," Dr. Barker says, "they all would risk the most for a full face transplant."

But Carson Strong, Ph.D., asks, "If the Phantom of the Opera were offered a face transplant, would he have the capacity to say no, or would he be so desperate for a new face that he would grasp at straws?" He is professor in the department of human values and ethics at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

"I applaud that they've done surveys," says Dr. Caplan. "But I worry that the screening, testing and psychological evaluation have not yet been done by independent researchers."

Risk worth benefit

Nevertheless, Dr. Barker says the university's research has convinced his team that the risks of a face transplant, at least in the eyes of people who understand them and could benefit from the procedure, are worth the benefits.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.