- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

News

Article

Neuronal-Like Communication Between Non-Neuron Skin Cells May Initiate Melanoma

Author(s):

According to study authors, this electrical communication between skin cells may have the potential for therapeutic implications.

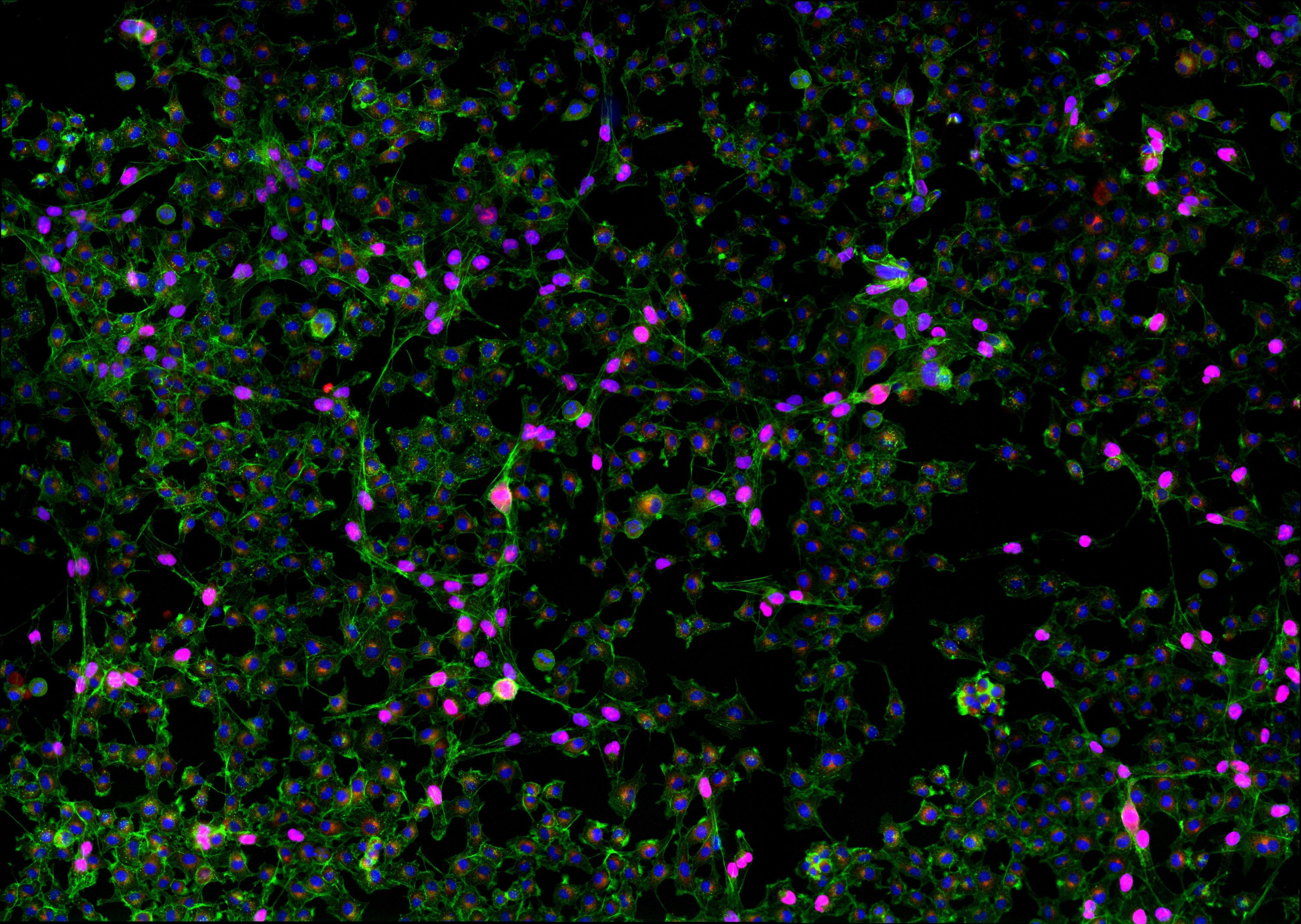

In melanoma, melanocytes skin cells release melanin-containing vesicles to keratinocytes, neighboring skin cells, to give skin its color. Melanoma commonly has mutations in genes such as BRAF or NRAS.1

dr322/AdobeStock

Previous work had found that the developmental state of the cell plays a dominant role in this process because some melanocytes have a particular landscape that makes them acceptable for tumor development.1

Approximately half of melanomas have mutations in the BRAF gene, with these mutations appearing in many benign skin lesions as well.2

“This suggests that BRAF mutation is not sufficient for melanoma development and raises the question of why certain BRAF-mutated melanocytes develop into cancer, while others remain benign,” said study author Richard White, MD, PhD, a physician-scientist at the University of Oxford Branch of the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research and the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK), in a press release.2

Because melanocytes are fixed within a population of keratinocytes, the current study’s researchers examined whether the communication between melanocytes and keratinocytes was involved in the development of benign BRAF-mutated melanocytes into melanoma.2

By using zebrafish, mice, and human cells as models, the study researchers observed that the transfer of molecules between BRAF-mutated melanocytes and normal keratinocytes was critical to melanoma initiation. Transfers had occurred almost entirely between melanocytes and keratinocytes that were in direct contact with one another; this communication was mediated by the neurotransmitter GABA. The researchers noted that this was an unexpected finding, as GABA signaling is typically associated with neurons and not skin cells.2

“I would not have necessarily expected a neurotransmitter to be involved in the communication between skin cells,” said White in the press release. “Interactions between neurons and brain cancer cells have been reported, but here we observed neuronal-like communication occurring between 2 non-neuron cells.”2

Study results suggest that BRAF-mutated melanocytes may increase the rate of and transmit GABA to hinder the electrical activity between neighboring keratinocytes. This would allow for vesicle transfer between the 2 cell types, initiating the progression to melanoma. The investigators hypothesize that molecules that are carried by vesicles from melanocytes to keratinocytes can potentially trigger the secretion of cancer-promoting protein from keratinocytes; however, additional research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.2

The results, however, may not apply to all forms of melanoma due to the heterogeneity of the disease. Further, not all experiments were performed in preclinical models which could result in some discrepancy.2

The study authors noted that the findings potentially have therapeutic implications because they present the possibility of targeting GABA to treat or prevent melanoma; however, they emphasized that further research is necessary to understand the study’s clinical applications.2

“Something about normal electrical activity in keratinocytes appears to suppress the progression of BRAF-mutated melanocytes to melanoma,” said lead study author Mohita Tagore, PhD, a postdoctoral research scientist at MSK, in the press release. “Our findings indicate that some BRAF-mutated melanocytes are able to modulate this electrical activity through GABA in order to progress to melanoma…We typically consider electrical activity in the context of neuronal communication, but these observations implicate it in cancer development as well.”2

References

- Tagore M, Hergenreder E, Suresh S, et al. Electrical activity between skin cells regulates melanoma initiation. Cancer Discovery. 2021;12(19):473393. doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.19.473393

- American Association for Cancer Research. Electrical Signals Between Skin Cells May Influence Melanoma Initiation. News release. August 9, 2023. Accessed August 9, 2023.

[This article was originally published by our sister publication, Pharmacy Times.]

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.