- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

The role of the dermatologist in diagnosing, managing advanced basal cell carcinoma

Advanced basal cell carcinoma is a term whose frequency of usage has increased recently, in part, due to the introduction of the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. Advanced basal cell carcinoma (aBCC) is comprised of two subtypes of BCC associated with significant morbidity and mortality, locally advanced BCC (laBCC) and metastatic BCC (metBCC).

Advanced basal cell carcinoma is a term whose frequency of usage has increased recently, in part, due to the introduction of the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. Advanced basal cell carcinoma (aBCC) is comprised of two subtypes of BCC associated with significant morbidity and mortality, locally advanced BCC (laBCC) and metastatic BCC (metBCC).

Although basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy in the world, the incidence rate of metBCC is exceedingly low, between 0.0029-0.55 percent.1 On the other hand, locally advanced basal cell carcinoma is more common (about 1 percent) and may result in destruction of underlying appendages, nerves, muscle, bone and cartilage. Given the high incidence of BCC in general, even a low recurrence rate of 1 to 3 percent following surgery could lead to significant numbers of complicated and recurrent BCCs, some of which may eventually become advanced BCC.

A patient with multiple BCCs bordering central SCC, who was treated with cetuximab and vismodegib. The BCC demonstrated clinical response and SCC stable. (Photo: Timothy Mattison, M.D.)Some estimates suggest that more than 3,000 deaths may be associated with advanced BCC each year in the United States.2 Given that most of the advanced BCC that the practicing dermatologist will encounter are not metastatic BCC, this article will focus on the diagnosis and management of laBCC by dermatologists.

Diagnosis of laBCC

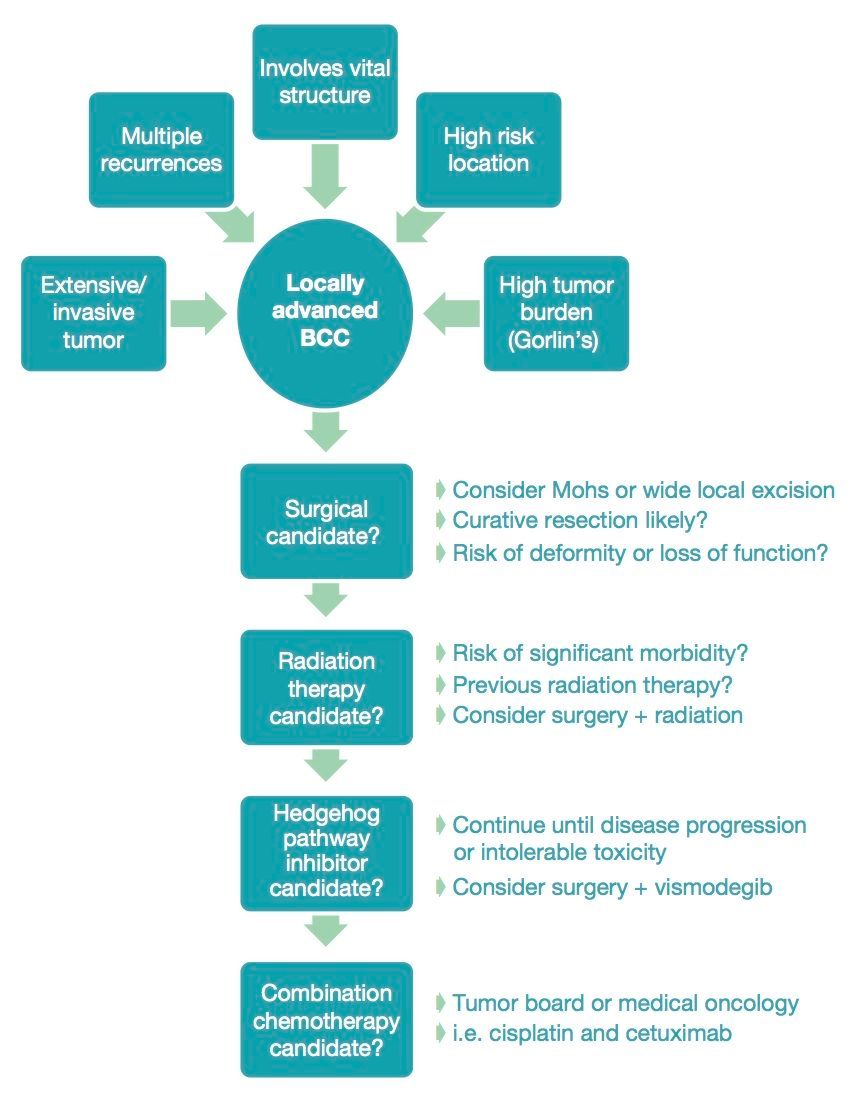

There are no definitive selection criteria for what type of BCC should be designated as locally advanced; that determination is generally made by the treating physician. Some of the clinical criteria for laBCC are listed in Figure 1: Algorithm for Identifying and Treating Locally Advanced BCC. These clinical criteria include extensive or invasive tumors, multiple recurrences, high-risk locations, and involvement of vital structures. High tumor burden may also be considered a criterion for laBCC even though individual lesions may not be severe.

It is important to note that not all laBCC cases should be treated with oral Hedgehog pathway inhibitors; these systemic drugs are appropriate only for laBCC cases that are not candidates for surgery or radiation. For example, multiple recurrences alone may justify a diagnosis of laBCC but not for treatment with oral vismodegib.

Table 1 reviews a representative range of laBCC cases that the authors have encountered in private practice and the treatment choices for each. Most of these cases of laBCC tend to develop in three types of patients. A majority of patients with laBCC have a long history of incomplete treatments resulting in persistent and discontinuous tumors that are unlikely to be cured by surgery alone. Some patients have histologically aggressive or indeterminate tumors that are very difficult to cure as in the case of morpheaform BCC. A few patients have severe disease exacerbated by neglect or limited access to medical care.

Regardless of the factors leading to laBCC, many patients with difficult BCC tumors have been misinformed that they have very limited treatment options.

Treatment for laBCC

A patient with morpheaform BCC of the eyelid and temple. He was treated with visomodegib and then Aldara, demonstrating partial response to the visomodegib and histological clearance after Aldara. (Photo: Snehal P. Amin, M.D., F.A.C.M.S.)Published studies involving laBCC are limited. Recent phase 1 and 2 studies involving vismodegib, however, have greatly expanded our understanding of the treatment options for severe cases of laBCC.3,4 As highlighted by the treatment choices for the cases listed in Table 1, most patients with laBCC need an individualized treatment plan with realistic therapeutic goals; many patients undergo multiple treatments and do not achieve histological clearance or tolerate therapy.

In addition to the size, location and histology of the BCC, additional considerations in choosing the best treatment include the curative potential of surgery, previous therapies, tolerance of side effects, risk of deformity, potential loss of function, patient’s life expectancy and cost.

Mohs micrographic surgery, even on recurrent and complex tumors, offers the best chance for cure and is the first choice of treatment for locally advanced BCC.5 Before definitive treatment selection is made, it is important to obtain consultations from surgical specialties regarding the possibility for curative resection.

If outpatient surgery with an experienced Mohs surgeon is not possible, additional consultations with head and neck surgeons, surgical oncologists and academic tumor boards are essential before classifying a patient as an inappropriate candidate for surgery.

Radiation therapy is a second choice for laBCC and can often provide excellent cosmetic results with low recurrence rates.6 Most radiation oncology centers can accommodate patients with extensive or invasive disease in difficult locations. Patients often raise logistical concerns, citing the frequency of treatment sessions. Dermatologists must stress the expected benefits of radiation treatment and the limited number of treatment sessions when counseling patients.

Oral hedgehog pathway inhibitors

For laBCC patients who are not surgical or radiation therapy candidates, dermatologists must consider oral Hedgehog pathway inhibitors. Currently, the only Food and Drug Administration-approved drug indicated for laBCC is vismodegib (Erivedge, Genentech). Due to the clinical heterogeneity and range of severity of laBCC, the decision to start systemic therapy with vismodegib can be challenging. The limited amount of published data regarding the appropriate duration of treatment, recurrence rates after stopping drug, combination treatments with surgery or other drugs, presurgical or postsurgical utility, potential persistence of subclinical tumor islands and acquired resistance contributes to the therapeutic challenge.

A patient with invasive BCC (neglected disease) in both orbits and the left cheek. There was no response to treatment with vismodegib. (Photo: Eli Saleeby, M.D.)

The FDA-approved label recommends continuation of vismodegib until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.4 Many prescribing dermatologists advocate discontinuation of drug once histological clearance is achieved.7

Some dermatologists have resorted to an off-label alternating monthly therapeutic schedule in order to diminish side effects. A one-month drug holiday has been a useful strategy to help patients deal with severe side effects. Once the drug is stopped, side effects based on the mechanism of action of vismodegib including alopecia improve quickly. Based on the same mechanism of action, the potential for regrowth of tumor cells even in histologically cleared areas still needs to be fully evaluated.

Next: Side effects from vismodegib

Vismodegib side effects

Even though dermatologists have a long history of prescribing systemic medications with significant side effects (i.e., methotrexate, isotretinoin, biologics), the vismodegib side effect profile requires special attention. In addition to the embryotoxic nature of the drug, the three main side effects to counsel patients about are muscle spasms, alopecia and taste disturbances. Even though these side effects tend to be mostly grades 1 and 2, the discontinuation rate for patients while taking vismodegib was approximately 50 percent, of which 15 percent was directly attributed to adverse effects.4

A patient with nodular BCC (neglected disease) on the chest, treated with vismodegib and then surgery. There was histological clearance on surgical pathology. (Photo: Snehal P. Amin, M.D.)Additional prescribing information for vismodegib is presented in Table 2. Regular dermatology visits are integral to helping patients manage side effects while on drug and monitoring for recurrence after drug therapy.

It is important to stress that once laBCC treatment with vismodegib is initiated, surgery or radiation are not contraindicated. It is unclear, however, if vismodegib is appropriate as a strategy to reduce tumor size prior to surgery or to treat residual tumor after surgery. The authors currently do not recommend combining vismodegib therapy with surgery unless the tumor margins are very well defined clinically.

Until information about rates and histological patterns of recurrence - if any - after stopping vismodegib is published, partially excising histologically cleared skin does not seem logical. In our personal experience, although presurgical vismodegib does not reduce the diameter of the eventual surgical defect, the debulking and thinning effect of vismodegib on large ulcerated tumors clearly makes the surgery simpler with respect to blood loss, delineation of tumor, and examination with the Mohs histopathology method. The debulking effect (i.e. partial response) may also allow for the treatment of thinned tumors with topical chemotherapies or immunomodulators even if vismodegib does not clear the histological tumor.

LaBCC and role of the dermatologist

Most patients with laBCC have long and complicated clinical courses with visits to multiple dermatologists, surgeons and other specialists. When they do arrive in the next dermatologist’s office, it is important not to simply refer these patients to another specialist.

We believe that the dermatologist should play the central role in the care of patients with laBCC. Even though most general dermatologists will not be performing a wide local excision or Mohs surgery in their office for these laBCC patients, all dermatologists, by the very nature of their diverse training and practice, understand both medical and surgical options as well as radiation therapy.

Figure 1 demonstrates an algorithm for identifying and treating locally advanced BCC (Source: Snehal P. Amin, M.D.)In addition, dermatologists are best positioned to clinically and histopathologically monitor patients with laBCC regardless of their treatment course with regular skin exams and full thickness skin biopsies.

In the next few years, several new topical and systemic agents as well as novel imaging techniques will become available. New oral Hedgehog pathway inhibitors, such as sonidegib, are currently undergoing trials and could potentially offer improved side effect profiles, increased efficacy or even decreased resistance potential.8

Potential hedgehog pathway inhibitors such as itraconazole and arsenic trioxide may play an important role in treatment of vismodegib resistant tumors.9 Additionally, topical smoothened inhibitors under current study may be useful in cases where oral vismodegib is not tolerated.10

Future articles in this series regarding aBCC will review the current state of research as well as the impact and management of aBCC in elderly patients. The introduction of new treatments for metBCC and laBCC was a pivotal development in dermatology, translating basic science in to clinical practice. The focus on laBCC represents an important opportunity for dermatologists to continue their role as skin cancer experts.

Disclosures: Dr. Krishan reports no relevant financial interests. Dr. Amin has participated on the advisory board for Genentech and is a paid speaker.

References:

1. von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10(6):1043-1060

2. Mohan SV, Chang ALS. Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Epidemiology and Therapeutic Innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2014;3:40-45

3. Chang ALS, Soloman JA, Hainsworth JD, et al. Expanded access study of advanced basal cell carcinoma patients treated with the Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, vismodegib. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(1):60-69

4. Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(23):2171-2179

5. Chren MM, Linos E, Torres JS, et al. Tumor recurrence 5 years after treatment of cutaneous basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1188-1196

6. Avril MF, Auperin A, Margulis A, et al. Basal cell carcinoma of the face: surgery or radiotherapy? Results of a randomized study. Br J Cancer. 1997;76(1):100-106

7. Ibrahim SF. Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma: Treatment Overview. The Dermatologist. 2014;22(3):32-34

8. Petrou I. Smoothened inhibitors provide new options for BCC treatment: New therapies may circumvent inappropriate surgery, radiation therapy. DermatologyTimes. http://dermatologytimes.modernmedicine.com/dermatology-times/news/smoothened-inhibitors-provide-new-options-bcc-treatment. Accessed June 26, 2014.

9. Kim J, Aftab BT, Tang JY, et al. Itraconazole and arsenic trioxide inhibit hedgehog pathway activation and tumor growth associated with acquired resistance to smoothened antagonists. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(1):23-34

10. Skvara H, Kalthoff F, Meingassner JG, et al. Topical treatment of basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome with a smoothened inhibitor. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(8):1735-1744

11. Lyseng-Williamson KA, Keating GM. Vismodegib: a guide to its use in locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(1):61-64

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.