- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Article

Unveiling leprosy: 4,000-year-old skeleton from India now earliest evidence of disease

Author(s):

World report - A 4,000-year-old skeleton discovered in Balathal, India, bearing signs of leprosy is the earliest known skeletal evidence of the disease, and is also the first evidence of leprosy in prehistoric India.The online journal PloS One published the research by Appalachian State anthropologists in May of this year.

World report - A 4,000-year-old skeleton discovered in Balathal, India, bearing signs of leprosy is the earliest known skeletal evidence of the disease, and is also the first evidence of leprosy in prehistoric India.

The online journal PloS One published the research by Appalachian State anthropologists in May of this year.

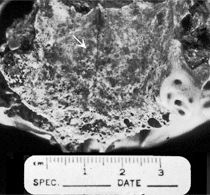

The discovery in India of a 4,000-year-old skeleton of a leper may shed new light on the origins of the disease.Photo: Gwen Robbins, Ph.D.

"Not much is currently known about the origins or history of this disease. Previously the oldest skeletal evidence was from less than 2,500 years ago, a time when we have historical records to suggest that Europeans first became aware of the disease," says lead author Gwen Robbins, Ph.D., assistant professor, department of anthropology, Appalachian State University, Boone, N.C.

Gwen Robbins, Ph.D.

"Although there was much speculation that it had spread to Europe from Asia or Africa, the origin and initial migrations were unknown. This paper sheds some light on those questions," she says.

Leprosy primarily affects the peripheral nerves, skin, upper respiratory tract, eyes and nasal mucosa.

Dr. Robbins and colleagues differentiated leprosy from other disease conditions in the skeleton because, she says, the principal change to the skull that they would expect to see in cases of leprosy is rhinomaxillary syndrome, which involves loss of bone around the pyriform aperture, destruction of the nasal spine, and loss of bone at the anterior alveolar process.

"“In the Balathal skeleton, we have clear evidence of rhinomaxillary syndrome and bilateral expression of infection in the splanchnocranium. These changes are specifically associated with lepromatous leprosy," Dr. Robbins says.

"Given the patterning of lesions, the absence of key diagnostic criteria for treponemal infection, tuberculosis and osteomyelitis, it is argued here that this skeleton represents the oldest example of lepromatous leprosy in the world."

Dermatologists might be interested to know, Dr. Robbins says, that because this skeleton indicates leprosy was known in India by 2000 B.C., it supports translations of the Atharva Veda, the oldest reference to the disease.

These texts, composed prior to the first millennium B.C., also were the first to link leprosy and tuberculosis as related conditions, at least in terms of treatment.

"We now know the two are closely related biologically, although of course their effects on humans are very different," Dr. Robbins says.

The Sanskrit writings suggest an herbal remedy for treating both leprosy and tuberculosis. The herbal remedy referenced in Sanskrit writings in 1000 B.C. is kustha - a word that referred to leprosy and also to the plant used to treat its symptoms.

The word has usually been translated as representing Solanum indicum, commonly known as Indian nightshade, according to Dr. Robbins.

Dr. Robbins is in the grant-writing stage for the next step in the research, which is to recover ancient DNA from the skeleton to determine if the strain of bacterium that infected the sufferer from Balathal is similar to strains common in Africa, Asia, and Europe today.

If successful, this work could shed additional light on the origin and transmission routes of the disease.

Leprosy today

At the beginning of 2007, the registered prevalence of leprosy in the world was 224,717 cases, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The number of new cases detected during 2006 was 259,017, as reported by 109 countries.

The global number of new cases detected during the past five years has decreased at an average rate of nearly 20 percent per year, largely due to the success of early diagnosis and treatment, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Today, leprosy is found mainly in Angola, Brazil, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, India, Madagascar, Mozambique, Nepal and the United Republic of Tanzania. The disease is extremely rare in the United States, with about 100 to 200 reported new cases per year, occurring mostly along the Gulf Coast and in Hawaii, Massachusetts and New York, according to NIH.

Dermatologists treat most cases in the United States, because most patients present with a skin rash, according to Samuel L. Moschella, M.D., senior consultant, department of dermatology, Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, Mass.

"Rarely, it will present solely as either an eye disease or nerve disease," Dr. Moschella says.

Diagnosis of leprosy, according to the NIH, is typically based on clinical symptoms, especially localized skin lesions that show sensory loss. Thickened, enlarged peripheral nerves are also a hallmark of the disease.

Dermatologists and others have learned about the importance of multi-drug treatment for leprosy from their experiences treating tuberculosis, the dermatologist says.

WHO recommends multidrug therapy with dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine. Aspirin, prednisone or thalidomide can help to control inflammation, according to Medline Plus.

Today’s drug regimen works well, according to Dr. Moschella, but the search goes on for more effective drugs that will treat leprosy more quickly.

Either one or two years of therapy are currently needed, depending on the severity of the disease, Dr. Moschella says.

Leprosy patients who visit U.S. dermatologists usually are carrying the disease from outside U.S. borders, particularly from Brazil. Dr. Moschella says that of the last 15 patients he has seen with the chronic disease, all have been immigrants from Brazil.

"Any doctor who sees a rash and notices that the patient is from Brazil and notices that the rash is a little different than what he usually sees, he’d better start thinking about leprosy," Dr. Moschella says. DT

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.