- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Mohs micrographic presents challenges in kids

Author(s):

While Mohs micrographic surgery is well established as a safe and effective therapeutic modality in adult patients, it is not as commonly used in pediatric populations. There are unique challenges to performing Mohs surgery on pediatric patients, especially with patient cooperation. Multidisciplinary planning may be needed.

Although Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) has long been established as a safe and effective therapeutic modality for the treatment of a variety of skin tumors in adults, little is known regarding its use in children and adolescents. A recent review study1 looked at the unique challenges encountered when employing this technique in the pediatric population and highlighted how clinicians can best circumvent these obstacles in order to help facilitate the appropriate use of Mohs in children.

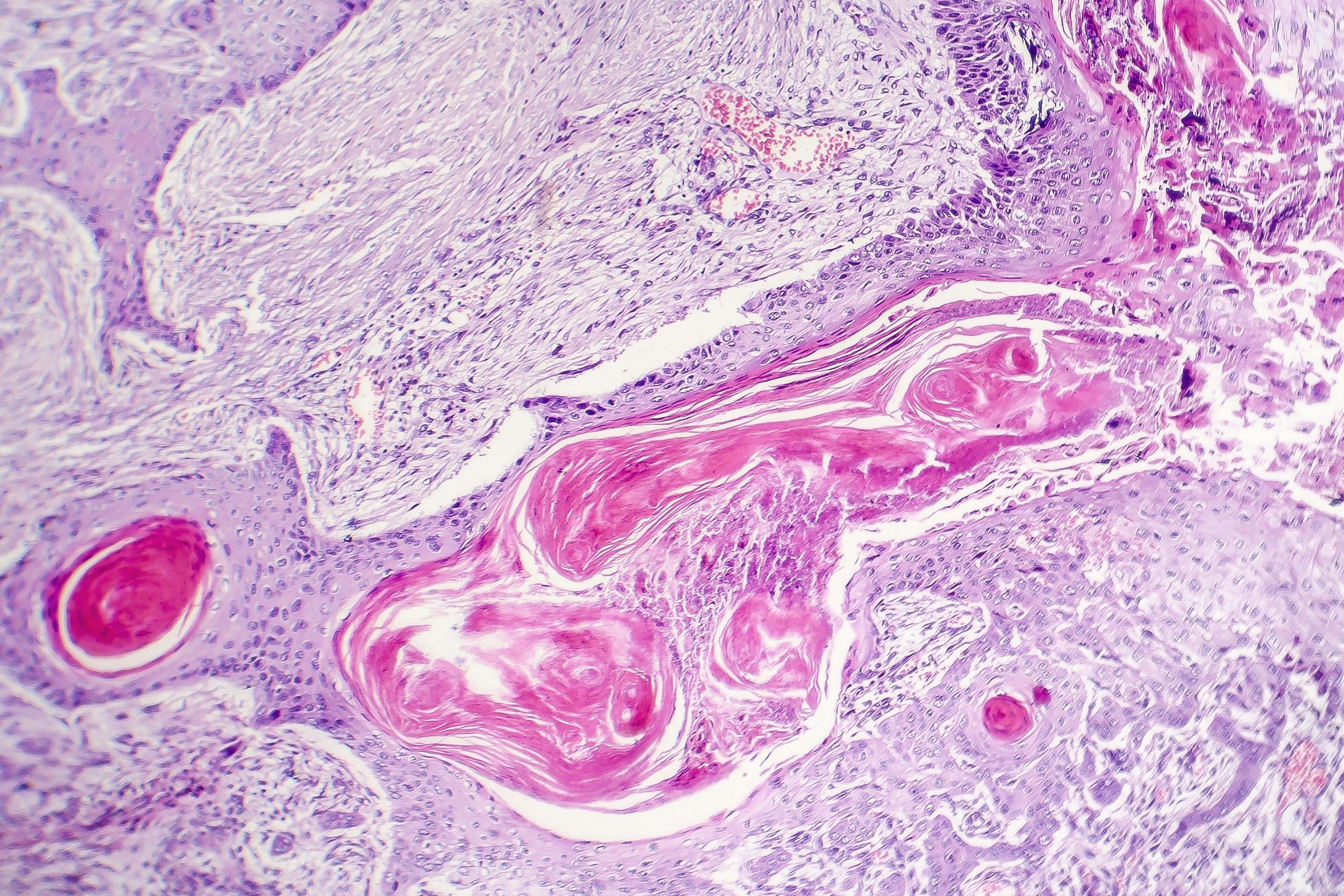

Typically performed in an out-patient setting, Mohs involves surgical excision and intraoperative assessment of tumor margins by the surgeon. The procedure is characterized by realtime histopathologic margin control and the ability to spare healthy tissue, particularly in cosmetically sensitive areas, resulting in better cosmetic outcomes as well as high cure rates. Although occurring less commonly than in adults, aggressive cutaneous tumors are also seen in children and Mohs can provide significant advantages in terms of margin control and minimization of surgical margins.

“In the pediatric population, this can be especially beneficial given the patients’ small body surface areas, and tissue preservation can be instrumental in helping to avoid functional and cosmetic morbidity. Mohs has not yet become first-line treatment in the pediatric population for challenging skin tumors. As such, I believe there needs to be an increased awareness amongst dermatologists and pediatricians who care for these patients regarding the benefits of Mohs as well as the challenges that are particular to this age group and how these challenges can be best overcome to provide optimal patient care,” says Hanieh Zargham, M.D., Division of Dermatology, Montreal General Hospital, McGill University Health Center, Montreal, Canada.

Dr. Zargham and colleague Amor Khachemoune, M.D., recently performed a comprehensive systematic review of the PubMed and EMBASE electronic databases including English, Spanish and French language literature articles that reported on the clear specification of the use of ‘slow Mohs’ and ‘modified Mohs’, and the use of this technique in patients younger than 18 years of age. In the final analysis, 87 articles were identified that included 111 patients ranging in age from 6 weeks to 17 years (median age 11 years), and a total of 123 resected tumors. A predisposing comorbidity was noted in 10 percent of patients (n=11) with the most common being xeroderma pigmentosum (n=3). The most common tumor treated was dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (n=62), followed by basal cell carcinoma (n=30), and most common location of lesions was the head and neck, followed by the trunk and extremities.

Data showed that 12 patients underwent general anesthesia, 7 had local anesthesia, and one patient had conscious sedation, while all other articles did not specify the means of anesthesia. Three patients reported complications consisting of a cellulitis, a seroma and a minor wound dehiscence and only one patient had a recurrence noted at 44 months post-op. The researchers found that the most commonly cited challenges in the application of Mohs in the pediatric population included patient cooperation, concerns for safety of prolonged general anesthesia, availability of a Mohs surgery service in the pediatric setting, and access to a histopathology lab experienced in MMS sectioning.

Performing any surgical procedure, especially a longer one such as Mohs, can be particularly difficult in children and each age group has their own unique set of challenges. There are several challenges regarding the procedural logistics of Mohs in children however, according to Dr. Zargham, the biggest one may be the unpredictability of patient cooperation, especially when performed under local anesthesia.

“While younger children are usually upset about being restrained, older children usually have an anticipation of pain that can lead to anxiety and an unwillingness to cooperate, which can make the process difficult and impact time constraints of the surgical staff and healthcare facility,” Dr. Zargham says.

Screening a child’s psychological and developmental status during a preoperative consultation is important in assessing likelihood of cooperation. According to Dr. Zargham, clinicians should remember that there are several different pharmacological (i.e., injection techniques minimizing pain) and non-pharmacological approaches to facilitate patient cooperation. To the latter, the combination of swaddling and sweet solutions as well as hypnosis with imagery can be used to immobilize infants and toddlers during surgery, and distraction methods can be used for older children.

If the procedure cannot be performed under local anesthesia, then the discussion about general anesthesia can be undertaken. In these cases, multidisciplinary planning including dermatologists, pediatricians and other healthcare workers involved in the care of the child, preoperative imaging, ‘slow Mohs’, and using multiple cryostats for larger tumors can all be helpful in decreasing procedure time. In addition, using ‘slow Mohs’ with permanent sections is helpful when access to an MMS lab is limited.

“There may be numerous challenges to overcome when performing Mohs in children but we need to have a better understanding of these challenges and really think about practical ways how some of these challenges can be overcome so that we can facilitate the appropriate use of Mohs in children and provide the best patient care to our pediatric patients,” Dr. Zargham says.

Disclosures: No relevant disclosures were reported.

Reference:

1. Zargham H, Khachemoune A. Systematic review of Mohs micrographic surgery in children: identifying challenges and practical considerations for successful application. Am Acad Dermatol.2020 Oct 1;S0190-9622(20)32645-1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.052.Online ahead of print.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.