- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

2021’s Top Challenges Facing Physicians

Author(s):

In late 2020, our sister publication, Medical Economics®, conducted a Physicians Report asking physician audiences what they thought would be the most challenging issues they will face this year. Here is what the respondents said.

In late 2020, our sister publication, Medical Economics®, conducted a Physicians Report asking physician audiences what they thought would be the most challenging issues they will face this year. Here is what the respondents said.

Administrative burdens and paperwork

If doctors had to chart their feelings about practicing medicine, many would list “paperwork” as their chief complaint.

In countless surveys and studies, and across specialties, physicians consistently cite the time and energy they must devote to filling out forms and other administrative tasks near or at the top of their list of grievances. The mantra repeatedly heard throughout the profession is, “This isn’t why I went into medicine.”

The problem is worsened by electronic health records (EHR), now used by close to 90% of office-based physicians. Once seen as a way to streamline data documentation sharing, EHRs have become enormous time-sucks. A December 2016 study in Annals of Internal Medicine found that physicians in outpatient settings spent about 27% of their day on direct clinical face time with patients, but 49% on EHRs and desk work. Many also worked up to 2 hours every evening on EHR-related tasks.

More recently, the proliferation of quality metrics physicians must document, although well-intentioned, has resulted in another layer of time-consuming administrative tasks for them and their staffs.

“Payers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) with their reporting requirements are trying to do the right thing and reward quality care, but the process and metrics we have today are adding to the bur- den with little evidence it is helping quality,” David Gans, MHA, senior fellow of industry affairs for the Medical Group Management Association, told Medical Economics®.

The growing number of treatments and medications requiring prior authorizations from payers is yet another source of administrative frustration for physicians and their staff. In a 2020 American Medical Association (AMA) survey, 86% of respondents described the administrative burden of prior authorizations as “high or extremely high.”

Similarly, respondents to the Medical Economics® Physician Report said prior authorizations consumed, on average, more than 16 hours per week of practice time, including 11.6 hours for staff members and 4.6 hours for themselves.

Paperwork and administrative requirements are also linked to the alarming increase in physician burnout rates, especially among primary care doctors. When Medical Economics® asked doctors what contributed to their feelings of burnout, 31% cited “paperwork”—more than twice the percentage of the second-leading cause, a poor work-life balance.

“The data show that the things that cause burnout are the things that get in the way of why you went into medicine in the first place, such as being able to provide the kind of care you want to provide to your patients,” Jack Resneck, MD, immediate past chairman of the AMA board of trustees told Medical Economics® in an interview this year.

Fortunately, there are steps physicians can take to reduce their administrative burden, starting with EHRs. Gans suggested that doctors and practices work with their EHR vendor on ways to automate data reporting, such as tailoring prompts according to patients’ specific requirements. For example, in patients with diabetes, the EHR might be programmed to provide reminders of the need for foot and eye exams and report to payers that the patient received the reminder. In addition, some EHRs now offer the option of automatically reporting some quality data to CMS.

Employing scribes can also help to reduce paperwork and other administrative burdens. A 2018 study in JAMA Internal Medicine concluded that their use was associated with significant reductions in EHR documentation time and “significant improvements in productivity and job satisfaction.”

Ultimately, doctors probably need to accept that paperwork and administrative tasks will be an inescapable part of practicing medicine— particularly with the spread of value-based care models, which usually require detailed tracking and reporting of quality metrics.

“In the long run, value-based reporting is going to be a requirement from all payers,” Gans predicts.

Getting paid and seeing enough patients

Generating enough revenue to keep a practice open requires knowing the intricacies of medical coding to ensure reimbursement is maximized, and also recognizing trends that keep patients coming back.

Getting paid is regularly listed as a top challenge facing physicians, according to the 2020 Medical Economics® Physician Report.

The good news for physicians who primarily deliver office and outpatient services is that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) has made significant changes to evaluation and management (E/M) coding and documentation to make the process simpler.

For 2021, there are 3 areas physicians need to focus on to make sure they get paid.

Understand E/M changes

According to coding experts, E/M codes are now much simpler Physicians will not select an E/M code based on total time spent during the encounter or medical decision making, whichever one pays more.

For medical decision-making (MDM), gone is the complicated points system derived from the number of treatment options, the complexity of data, and morbidity risks. The new MDM table includes easy-to-understand requirements and compensates them for complex cases, regardless of time spent, as long as documentation supports medically necessary services.

In addition, physicians now get credit for many tasks, including reviewing and interpreting test results, speaking with family members if a patient cannot provide their own history, and discussing patient treatments with another health provider or other professional involved in their care.

For time-based billing, physicians can now count the total time on the date of the encounter that may or may not include counseling and care coordination. Doctors may also count, among other tasks, documenting clinical information in the electronic health record (EHR), ordering medications or tests, preparing to see the patient, and referring the patient to and communicating with other health care professionals.

Physicians should contact their payers to verify whether they will adopt the CMS changes. Some payers may continue to require code selection based on history, exam, and MDM. They may also have requirements for individual codes.

The most important thing is to ensure that services performed match the documentation.

“Remember that if it’s not documented, it didn’t happen,” says Dreama Sloan-Kelly, MD, CCS, president of Dr Sloan-Kelly Consulting, a medical coding consulting company.

Master telehealth payments

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic closed many primary care offices throughout the country, forcing physicians to quickly adopt telehealth as the only way to see patients and keep revenue up.

To say telehealth was a lifeline for practices during the pandemic is an understatement. According to the Medical Economics® 2020 Technology Survey, more than 93% of physicians used telehealth to see patients during 2020, and 77% of them were using telehealth for the first time.

CMS and private payers made many emergency exceptions to laws making telehealth more accessible for both patients and physicians and added or increased reimbursement for virtual visits to match payment rates for in-office visits.

But the CMS changes were made as part of the federal government’s public health emergency declaration that will end whenever the pandemic passes. Although no one knows for sure when that will happen, doctors need to be ready for a sudden s telehealth reimbursement shift. Some private payers have already rescinded reimbursement for certain telehealth visits as public confidence for in-office visits has increased.

Experts say physicians must balance keeping telehealth available for patients who are not comfortable coming into the office to capture as much revenue as possible, knowing that at some point in 2021, it’s likely that reimbursement for it may dry up.

Before the pandemic, telehealth reimbursement was extremely limited. Even if reimbursement remains for some services, it may not be at the same level as for an in-office visit, so doctors need to understand their telehealth investment return both now and when the public health emergency ends.

Embrace the data

Experts say fee for service (FFS) isn’t going to vanish in 2021, but more contracts will focus on value-based care, and the lifeblood of any value-based care contract is data. Payers want data to evaluate the most effective physicians, and the top performers get the best bonuses.

Participating in the most lucrative forms of value-based care requires that physicians have plenty of data on their outcomes and show improvement in the ability to keep patients out of the hospital. An investment in software and equipment may be necessary to fully master all the data points within a practice. Without it, doctors will be at a disadvantage to both participate in and excel at value-based care.

“The key is for us to break the fallacy that FFS is a good way to pay for primary care,” says Farzad Mostashari, MD, the former director of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and current CEO of Aledade, a company that assists small practices with transitioning to value-based care models. “We shouldn’t be basing primary care payments on that—it should be on the value created, and we need to move towards more person-based rather than transactional.”

Physician burnout and autonomy

The perennial issue of physician burnout has only been intensified by the equipment shortages and shutdowns of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Despite increased awareness in the health care system, the same problem persists.

The 2020 Medical Economics® Physician Burnout Survey found that burnout is pervasive among physicians, with 91% of doctors saying they have felt burned out from practicing medicine at some point in their career. A further 71% of physicians reported feeling burned out at the time of the survey.

When asked what caused their burnout, 31% of physicians said too much paperwork and government/payer regulations, 15% cited poor work-life balance, and 12% said the COVID-19 pandemic.

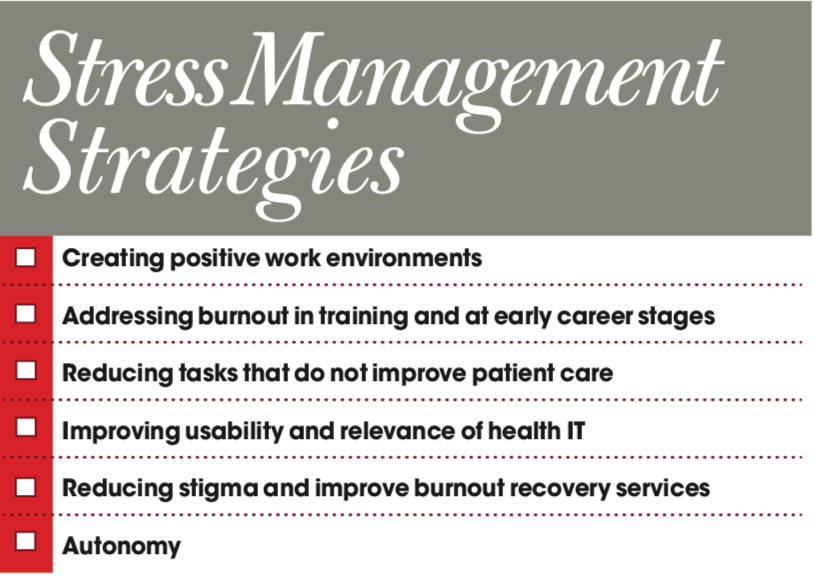

Although little can be done on the ground concerning increased stressors from the pandemic, there are ways health care leaders can reduce the underlying issues.

Tips

Howard Baumgarten, LPC, has extensive experience working with physicians who feel burned out. He says there are 3 categories of burnout physicians may experience: physiological, which can take the form of physical symptoms like headaches and high blood pressure; mental/emotional, which can take the form of anxiety and depression; and behavioral, which can take the form of increased alcohol use or smoking, overspending, and not sleeping.

Baumgarten says that once a physician starts feeling burnout symptoms, they should take steps to fight it. He gave some helpful tips for physicians to prevent feeling the heat of the health care system.

The first strategy is to aim for 7 to 8 hours of sleep, starting at the same time every night, and avoiding both drinking alcohol and screen time before bed. The next is to get 30 minutes of aerobic exercise 4 or 5 times a week mixed with some muscle-building exercises. Physicians should also avoid sugary and fried foods and do something that makes them feel good, such as a hobby.

The National Academy of Medicine released a report early in 2020 saying personal stress management strategies are insufficient to tackle the burnout problem facing health care. Although some of the academy’s suggestions relate to structural issues, independent practice leaders can adopt them.

Also, according to the same burnout survey, 11% of physicians experience burnout due to a lack of autonomy or career control.

Wendy Dean, MD, a psychiatrist, and president and cofounder of Moral Injury of Healthcare, says that following the long period of rigorous training, focusing on independent, critical thinking with strict adherence to algorithms based on reimbursement policies can be grating.

Beyond the big systemic hurdles that must be crossed to get this issue under control, Dean recommends that physicians learn how the incentives are aligned at their health care institution.

“Understand how reimbursement happens, what the incentives are at their entity, and whether they can negotiate to build bridges with the administration, build bridges with other licensees so that everyone can work together to start fixing things at the local level,” Dean says.

According to Dean, by talking to fellow physicians, they can see what the patterns are and where the stumbling blocks may be.

“As you start to look into that more and more, you can quickly become an expert and can have the tools available to you to change what that problem is,” Dean says.

Resources

Susan T. Hingle, MD, professor of medicine at Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, says there are burnout resources available on the websites of most major physician organizations, such as the American College of Physicians for internists. She says many hospital systems also offer support phone lines to help deal with the increased stress from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I want people to know that those [resources] are available and know that there’s no shame in asking for help,” Hingle says. “That’s how we’re all going to get through this: by helping each other and getting through it together.

Hiring and retaining clinical staff

A practice is only as good as the individuals who work there but finding and keeping the right them can seem like an insurmountable task. This task can be compounded with the uncertainty and increased scrutiny introduced by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

In a recent entry in weekly studies performed by the Larry A. Green Center and the Primary Care Collaborative on how COVID-19 has affected primary care practices, 35% of physicians say hiring new staff is a significant obstacle to their practice.

With this perennial problem only getting worse, the question remains for physician leaders on how to hire, motivate, and retain clinical staff.

Tips

Target the talent by looking for candidates from areas similar to those in the practice. This familiarity can smooth over some of the wrinkles the new staff member may feel starting at a practice.

Another suggestion is to adjust the payment system to reward hard work or to boost the total compensation package. Packages can take the form of creating bonuses for staff members who meet productivity goals, giving employees a sense of how to earn more without leaving the practice.

The practice leader can also consider offering staff members growth opportunities, such as enabling them to pursue more education through training. Sometimes the cost of training and giving the employee a raise can be a lower cost compared to hiring another employee for new duties.

Personalized benefits, such as flexible hours or more vacation time, can be a useful recruitment tool and a motivator for current staff members. Allowing newly hired physicians to hire their own care teams or set their office hours can increase their motivation.

All these changes should be documented and formalized so that, even if employment packages are individualized, they do not appear to be capricious.

Millennials

An often overlooked source for clinical staff is the newest batch of medical school graduates. Millennials can be a key part of a health care team.

Andrew Hajde, CMPE, assistant director of association content at Medical Group Management Association in Englewood, Colorado, says the health care system is reaching a point where millennial physicians re becoming the only ones left to pick up the slack of retiring boomers and Gen Xers before Generation Z comes of age.

When hiring millennials, it is important to remember that the cohort tends to put a premium on work-life balance and the feeling that their work has a purpose.

Natasha Bhuyan, MD, is a family physician and regional medical director with One Medical in Phoenix, Arizona, and is also a millennial. She says the members of her cohort no longer base their success on the hours they spend in the office or the number of patients seen.

“They measure success based on fulfillment of purpose, developing meaningful relationships with patients, having time to connect with patients and improve their behaviors, and see health results and outcomes change,” she says.

Millennial physicians are also aware that they need feedback and mentoring and can see the value in picking a senior employee’s brain to help them in their work.

Bhuyan says this new emphasis on mentorship is closer to coaching than in years past.

“How do we coach physicians to reach the top of their potential and beyond?” Bhuyan asks. “How do we push people beyond what they think is their best?

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.