- Acne

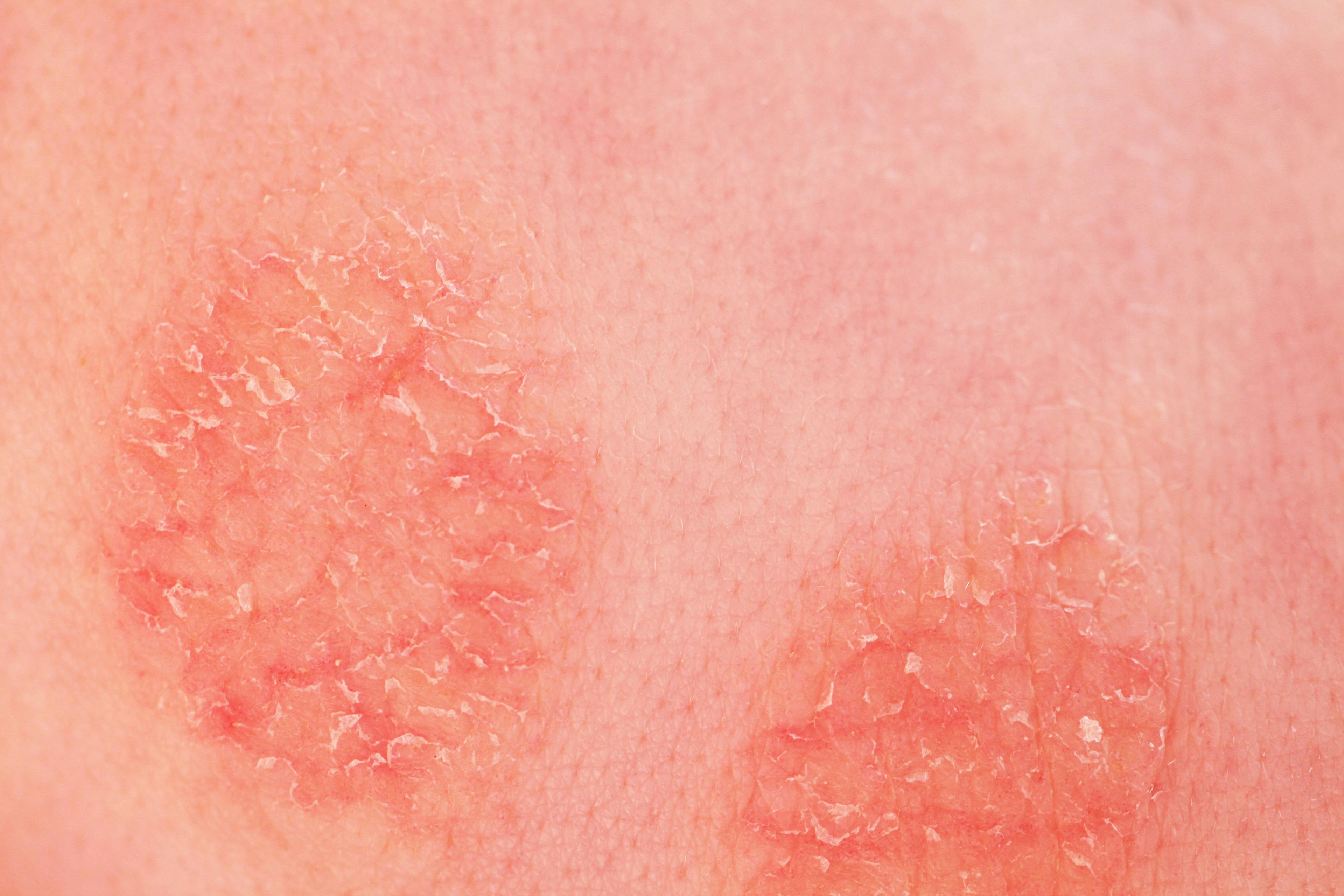

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

AAD Tackles Tough Issues in Upcoming Acne Update

Author(s):

American Academy of Dermatology’s updated guidelines on acne will cover dermatology’s hottest issues, from dosing and monitoring established medications to exploring new antibiotics and addressing antibiotic stewardship.

Five years of innovation and research have created numerous knowledge gaps in the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris.1 A work group recently formed by the academy to update its guidance will offer best-practice recommendations and safety precautions for the therapies, treatments, and devices developed to treat acne. Originally published in 2016, the new guidelines will be released in 2023 or 2024.

“Two major concerns are proper dosing of isotretinoin and laboratory monitoring for spironolactone and isotretinoin,” said Jonette Keri, MD, PhD, FAAD, associate professor of dermatology and cutaneous surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine in Florida, dermatology service chief at Miami VA Medical Center, and a member of the work group. “The updates will also provide guidance on new antibiotics and antibiotic stewardship as well as a broader knowledge of lasers and other light devices in use for acne treatment.”

She offered insights into the upcoming revisions in the AAD’s acne guidance as forum director for a session on translating evidence in practice for current acne guidelines and beyond at the American Academy of Dermatology Virtual Meeting Experience 2021 (AAD VMX) in April.2

Fellow speakers included Arun L. Pathy, MD, FAAD, dermatologist with Colorado Permanente Medical Group in Centennial and cochair of the work group revising the AAD acne guidelines3; Rachel Sabbag Reynolds, MD, vice chair, Department of Dermatology, and assistant professor of dermatology, Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Massachusetts4; Jonathan S. Weiss, MD, dermatologist with Georgia Dermatology Partners and Gwinnett Clinical Research Center in Snellville, Georgia5; and Andrea Zaenglein, MD, FAAD, professor of dermatology and pediatric dermatology at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center at Penn State University in Hershey, Pennsylvania.6

“In developing these new guidelines, not only have we recruited acne experts around the country, but we have an internal medicine physician, a pediatrician, and a patient advocate,” Keri said. “In fact, more than 51% of the work group does not have any relevant pharmaceutical interest. This is important because acne is not just treated by dermatologists. Primary care takes an active role, so we need to consider their view, as well as that of the patients.”

Keri told Dermatology Times® that there is always going to be room for improvement in the treatment of acne. “At least [for now], we do not have a magic bullet that gets rid of acne 100% for 100% of a person’s life,” she said.

However, the treatment option pipeline continues to flow, focusing on care until cure is a reality. New to the list of topical formulations are a minocycline foam (Amzeeq; Foamix Pharmaceuticals) and a retinoid, trifarotene (Aklief; Galderma).

“There are also new formulations of older retinoids, which have been evaluated [and found] to be helpful,” Keri said. “In addition, clascoterone [Winlevi; Cassiopea] is a new topical antiandrogen that is approved by the FDA but not yet released for use. This drug should be available soon.”

Sarecycline (Seysara; Almirall) is the first new oral antibiotic approved by the FDA in more than 40 years. One of its added benefits is that this tetracycline-derived small molecule drug is “less likely to generate resistance,” Keri said. “This is exciting because of the goal for antibiotic stewardship around the world.”

Patients also need to be educated about new oral antibiotics that are weight-based. “We have this stipulation with some antibiotics, but not for all of them,” Keri said. “Antibiotic stewardship ensures that you have the right antibiotic and the correct dose at the right time for the correct condition. You want to make sure that you are not giving too much or not enough.”

In Keri’s view, the dermatology community is working diligently to reduce its reliance on antibiotics. “As we get new mechanisms to treat acne, perhaps we can use fewer antibiotics,” she said.

The forum included a review of oral contraceptives approved for treating acne, as well as highlights of some of the controversies about adverse effects, including thromboembolic events with certain oral contraceptive pills and their safety.

“Currently, there are 4 FDA approved oral contraceptive pills for the treatment of acne, but there are many birth-control pills that are not FDA approved for the treatment of acne [that] can help,” Keri said.

Most of the oral contraceptive pills, whether they are approved or not for treating acne, are a combination of estrogen and progesterone. “Clinicians need to understand the difference of these 2 components, so they can make an informed decision about prescribing to their patients for acne,” Keri said. “There are oral contraceptive pills that are good for acne; however, these companies did not pursue approval for the treatment of acne.”

Keri tends to prescribe FDA-approved oral contraceptives that contain drospirenone (Yaz; Beyaz; Bayer) because the synthetic progestin acts as a potent antiandrogen. “However, there is a little controversy about their [adverse] effect profile, specifically thromboembolic events,” she said. “But the risk is slight.”

Spironolactone also is an antiandrogen used in adult women. “It has gained a lot of acceptance over the years for the treatment of acne, due in part to celebrity endorsement,” Keri said. “One of the [adverse] effects of spironolactone in men is gynecomastia, so it is not used in treating acne in males.”

Excellent results are achieved with spironolactone, according to Keri, with long-term treatment lasting for years. Laboratory monitoring may be required, however, because the medication can cause hyperkalemia, an increase in potassium.

Isotretinoin is a vitamin A derivative for severe scarring with nodular cystic acne or for acne that causes severe psychological implications for the patient. However, the systemic medication is surrounded by controversy over serious adverse effects, including malformations in the fetus.

“That [adverse] effect [teratogenicity] is undisputed, unlike concerns of depression and inflammatory bowel disease,” Keri said. “In the past, I believe people were simply being cautious about prescribing isotretinoin. Now, however, because of good epidemiologic studies, dermatologists are feeling increasingly comfortable about prescribing the drug.”

At Keri’s practice, dosing of isotretinoin is patient preference, although she favors typical cumulative dosing to 150 mg/kg. “But there are patients who need more of the drug or less,” Keri said. “There is variability in how much isotretinoin patients will need, and we are working to define the optimal dose for patients.”

Diet has become increasingly important in treating acne as well. “There is some evidence that milk aggravates acne,” Keri said. “Although some data suggested skim milk was more implicated, recent data does not support this. The jury is still out on the association between of milk and acne.”

“White” foods with a high glycemic load, such as white bread, rice, and pasta, also have been strongly implicated in exacerbating acne. “My patients tend to place too much emphasis on diet, although diet can be a contributor to acne,” Keri said. “Diet is more concerning for the female patient with polycystic ovarian disease. Diet intervention [watching the glycemic load/index] has been proven to help these patients specifically.”

The advantages of light-based devices vs traditional pharmaceutical therapies are also changing the acne treatment paradigm. Traditional treatments still tend to be first-line choices, but light- and laser-based therapies can be used for the patient who does not want traditional treatment or has failed traditional therapy and is able to pay the out-of-pocket expense—it’s generally not covered by insurance, according to Keri.

Other research gaps for acne include treating patients with skin of color and pregnant patients, as well as exploring the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying acne.

“A lot of work goes into the guideline development,” Keri said. “That is why it takes 2 to 3 years. We try to assess the validity of the evidence and attempt to make it user-friendly so that the guidelines can be a reference for the practitioner who is in a busy practice.”

Disclosures:

Keri is on the speakers bureau of VYNE Therapeutics and a consultant to Almirall.

Pathy, Sabbag, and Reynolds reported no financial or relevant disclosures.

Zaenglein is a consultant for Pfizer; an advisory board member for Dermata, Sol-Gel, Regeneron, Verrica Pharmaceuticals, and Cassiopea; and a contracted researcher for AbbVie, Arcutis and Pfizer.

References:

1. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(5):945-73.e33. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.12.037

2. Keri J, Pathy A, Weiss JS et al. Translating evidence into practice, current acne guidelines and beyond. American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX); April 23-25, 2021; virtual. Accessed May 4, 2021.

3. Pathy A. Guide development and clinical pearls. American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX); April 23-25, 2021; virtual. Accessed May 4, 2021.

4. Sabbag Reynolds. Spironolactone for the treatment of acne. American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX); April 23-25, 2021; virtual. Accessed May 4, 2021.

5. Weiss J. Isotretinoin guidelines. American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX); April 23-25, 2021; virtual. Accessed May 4, 2021.

6. Zaenglein A. Diet and acne. American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX); April 23-25, 2021; virtual. Accessed May 4, 2021.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.