- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

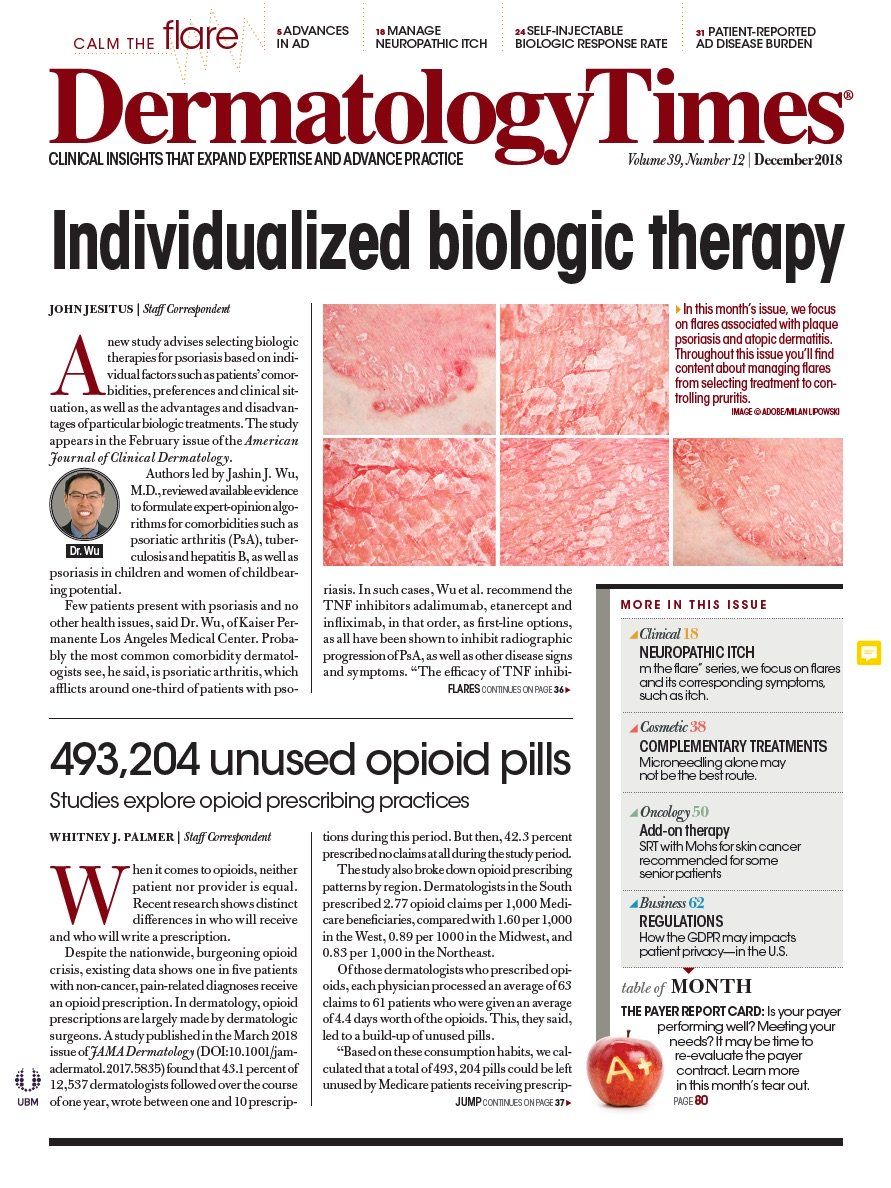

Dermatology Times

Advances in atopic dermatitis raise bar for treatment

Author(s):

In this article, Dr. Peter A. Lio discusses how recent advances in atopic dermatitis have led to a new standard of care, which aims to keep patients clear safely and maximize improvements in quality of life.

In this article, Dr. Peter A. Lio discusses how recent advances in atopic dermatitis have lead to a new standard of care, which aims to keep patients clear safely and maximize improvements in quality of life.

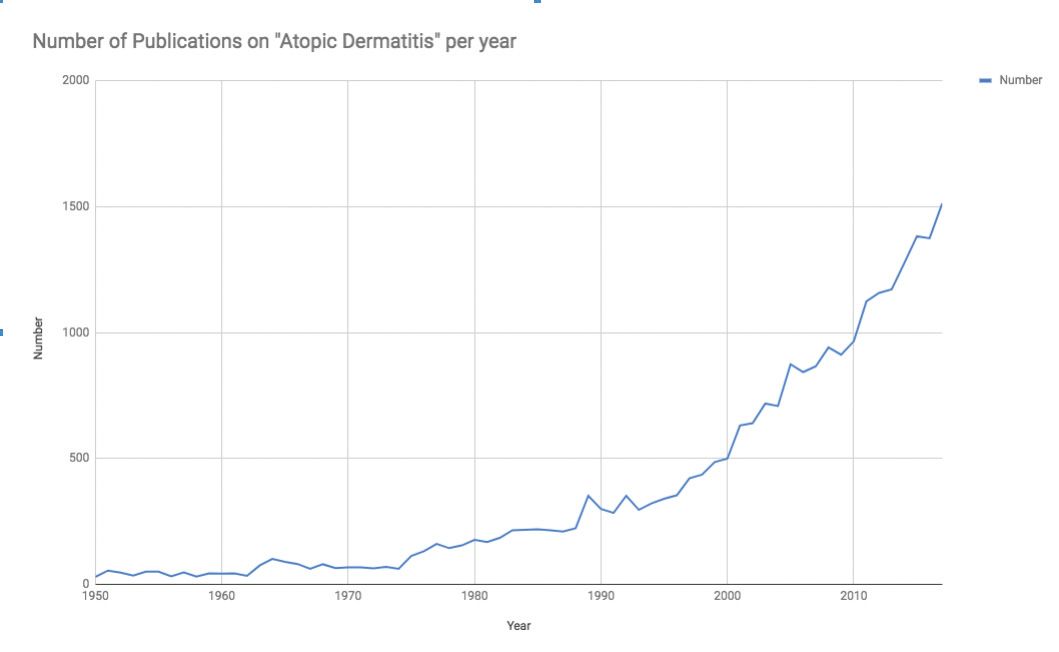

Source: Data extracted from Pubmed, search term = “Atopic Dermatitis” using Alexandru Dan Corlan. Medline trend: automated yearly statistics of PubMed results for any query, 2004. Web resource at URL:http://dan.corlan.net/medline-trend.html. Accessed: 2018-10-10, and data graphed with Numbers, Apple Inc.

Dr. Lio

In recent years there has been surging interest in atopic dermatitis (AD). This is evidenced by the near-exponential growth in the publication of papers dealing with AD (see Figure 1), as well as the now formidable pipeline of medications currently being studied.1

While the pipeline is extremely impressive in terms of potential therapeutic innovations, I’d like to take a step back and briefly look at three areas of advancement in AD from a broader perspective. Underpinning the possibility for these new treatments lies progress in conceptions of the disease, some of which are quite remarkable. I will discuss the microbiome, skin barrier dysfunction, and finally the emerging standard of care in AD.

THE MICROBIOME

The notable dermatologist Paul Unna suggested that the etiology of AD was due to “the inoculation of a germ.” He was far ahead of his time when he asserted that local treatment should “always have in view the destruction of every single germ in the depths of the epidermis”.2 His prescience is remarkable in light of the more than 120 intervening years during which we have, until very recently, largely ignored those germs in the epidermis. The microbiome has gone from more of a fringe topic to something “ripped from the headlines” and is now thought to be seemingly central to the pathogenesis of many diseases, including AD.3 As we have learned more about this microbiota imbalance, the contribution of Staphylococcus aureus has become increasingly clear, including its ability to secrete a toxin that actively contributes to dermatitis.4

Remarkably, these developments have unfolded in the context of a renewed push to heed Unna’s recommendation, perhaps starting with the concept that dilute bleach baths are helpful for AD, possibly by reducing the bacterial burden.5 This story has been significantly complicated, however, by papers showing dilute bleach baths have no effect on Staphylococcus,6 but instead may be anti-inflammatory,7 and perhaps may improve the skin barrier.8 Culminating in a recent paper that frustratingly concludes that bleach baths “do not appear to be more effective than water baths alone”,9 the only certainty is that we still have a lot to learn.

Confusion has opened the door for another controversial approach: mixing a topical antibacterial with a corticosteroid to directly decrease Staphylococcus. This approach, popularized by South African dermatologist Dr. Richard Aron, lacks randomized controlled trials, but has a mountain of anecdotal evidence and a small retrospective case series to support its use.10 It remains to be seen if and how this affects skin bacteria, but speaks to the fact that there remain significant unmet needs.

And we haven’t even gotten to the winding story of oral probiotics for both prevention and treatment of AD,11,12 or the more exciting new “microbiome transplant” work that suggests a totally different approach for restoring healthy skin flora.13 Suffice it to say, this is a hot topic par excellence, and will likely continue to develop over the next few years.

SKIN BARRIER DYSFUNCTION

Filaggrin is a structural protein in the stratum corneum and plays a critical role in maintaining the skin barrier. The discovery that null mutations in the filaggrin gene (FLG) are associated with AD led to a breakthrough in understanding the pathogenesis of the disease.14 This understanding has become increasingly sophisticated in the past decade, with a recent paper demonstrating regional variability in filaggrin processing that may actually begin to answer one of the “holy grail” questions in dermatology: why AD appears in some areas (such as the cheeks of infants) rather than others.15

Building on this concept of barrier dysfunction as “leaky skin”, the stakes have been raised by the increasingly clear notion that the ineffective skin barrier of AD may directly lead to the development of allergic sensitization (so-called transcutaneous sensitization) in animal models.16 In humans, it is strongly suggested to be equally true,17,18 and further trials are ongoing to verify this hypothesis.19 In the meantime, practical clinical guidelines have changed based on this notion: while previous guidance suggested delaying introduction of allergenic foods into the diet of high-risk children, those with AD are now encouraged to eat peanuts between the ages of 4-6 months of age (making sure to first allergy test those with severe AD and/or egg allergy). This has been shown to significantly decrease the development of peanut allergy.20,21

Perhaps most exciting, however, is the idea that skin barrier dysfunction is so central to AD, that artificially augmenting it with topical moisturizers may actually prevent the development of AD in the first place, not to mention the secondary diseases such as food allergy as discussed above. Two studies have demonstrated cutting the development of AD in high-risk patients by some 30-50% with moisturization alone. Larger studies are planned to verify and confirm these findings.22,23 The implications for preventing a disease with significant morbidity are tremendous, including from an economic standpoint, especially when estimates can reach annual U.S. costs approaching $4 billion.24

A NEW STANDARD OF CARE

All of these advancements in understanding and therapeutics are leading to a new standard of care: raising the bar so that the goal-for those who have missed the prevention window-is to get patients clear, keep them clear safely, and maximize improvements in quality of life. In the past several years, the significant, perhaps shocking to the uninitiated, impact on quality of life of AD has been further elucidated.25–27 Detrimental effects on sleep, work, school, leisure activities, and psychological well-being have all been described, with more recent papers also reporting a majority of patients experiencing pain in addition to the itch as yet another burden.28

An increasingly nuanced understanding of the pathogenesis of psoriasis has developed over the past decade, altering its perception from an unpleasant rash that patients must tolerate, to a truly systemic disease that is effectively treated with safe, incredibly effective agents. This decade of psoriasis has allowed for a new bar to be set in terms of therapeutic expectations.29 Finally, similar leaps in understanding AD are occurring and, as such, we must ensure that the aggressive approach to psoriasis is likewise followed with AD as our treatment armamentarium begins to fill in.

After many decades of darkness, we enter into a new era of AD armed with new knowledge and new tools that will hopefully bring light.

REFERENCES:

1. Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E. Systemic therapies in atopic dermatitis: The pipeline. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35(4):387-397.

2. Stelwagon L. Prurigo infantum; psoriasis-eczema; primary pigmented sarcoma of the skin; xeroderma pigmentosum; dermatitis herpetiformis. On the nature and treatment of eczema. Am J Med Sci. 1891;101:95-96.

3. Thomas S, Izard J, Walsh E, et al. The Host Microbiome Regulates and Maintains Human Health: A Primer and Perspective for Non-Microbiologists. Cancer Res. 2017;77(8):1783-1812.

4. Geoghegan JA, Irvine AD, Foster TJ. Staphylococcus aureus and Atopic Dermatitis: A Complex and Evolving Relationship. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(6):484-497.

5. Huang JT, Abrams M, Tlougan B, Rademaker A, Paller AS. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in atopic dermatitis decreases disease severity. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):e808-e814.

6. Hon KL, Tsang YCK, Lee VWY, et al. Efficacy of sodium hypochlorite (bleach) baths to reduce Staphylococcus aureus colonization in childhood onset moderate-to-severe eczema: A randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(2):156-162.

7. Leung TH, Zhang LF, Wang J, Ning S, Knox SJ, Kim SK. Topical hypochlorite ameliorates NF-κB-mediated skin diseases in mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5361-5370.

8. Perez-Nazario N, Yoshida T, Fridy S, De Benedetto A, Beck LA. Bleach baths significantly reduce itch and severity of atopic dermatitis with no significant change in S. aureus colonization and only modest effects on skin barrier function. In: Journal Of Investigated Dermatology. Vol 135. 2015:S37-S37.

9. Chopra R, Vakharia PP, Sacotte R, Silverberg JI. Efficacy of bleach baths in reducing severity of atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(5):435-440.

10. Lakhani F, Lee K, Lio PA. Case Series Study of the Efficacy of Compounded Antibacterial, Steroid, and Moisturizer in Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(3):322-325.

11. Huang R, Ning H, Shen M, Li J, Zhang J, Chen X. Probiotics for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:392.

12. Zhao M, Shen C, Ma L. Treatment efficacy of probiotics on atopic dermatitis, zooming in on infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57(6):635-641.

13. Myles IA, Earland NJ, Anderson ED, et al. First-in-human topical microbiome transplantation with Roseomonas mucosa for atopic dermatitis. JCI Insight. 2018;3(9). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.120608

14. Dennin M, Lio PA. Filaggrin and childhood eczema. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102(12):1101-1102.

15. McAleer MA, Jakasa I, Raj N, et al. Early-life regional and temporal variation in filaggrin-derived natural moisturizing factor, filaggrin-processing enzyme activity, corneocyte phenotypes and plasmin activity: implications for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179(2):431-441.

16. Jin H, He R, Oyoshi M, Geha RS. Animal models of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(1):31-40.

17. Tsakok T, Marrs T, Mohsin M, et al. Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1071-1078.

18. Flohr C, Perkin M, Logan K, et al. Atopic dermatitis and disease severity are the main risk factors for food sensitization in exclusively breastfed infants. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134(2):345-350.

19. Chalmers JR, Haines RH, Mitchell EJ, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of daily all-over-body application of emollient during the first year of life for preventing atopic eczema in high-risk children (The BEEP trial): protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):343.

20. Lio PA. Updated guidelines on peanut allergy prevention in infants with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101(6):398-399.

21. Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):803-813.

22. Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM, et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):818-823.

23. Horimukai K, Morita K, Narita M, et al. Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):824-830.e6.

24. Xu S, Immaneni S, Hazen GB, Silverberg JI, Paller AS, Lio PA. Cost-effectiveness of Prophylactic Moisturization for Atopic Dermatitis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(2):e163909.

25. Kouotou EA, Nansseu JR, Tuekam Tuekam EG, et al. Atopic Dermatitis in Cameroon: Quality of Life and Psychiatric Comorbidities among Affected Children and Adolescents Running Head: Atopic Dermatitis and Psychiatric Impairments. Clin Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;03(01). doi:10.21767/2472-0143.100027.

26. Vakharia PP, Cella D, Silverberg JI. Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life measures in atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):616-630.

27. Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(8):984-992.

28. Maarouf M, Kromenacker B, Capozza KL, et al. Pain and Itch Are Dual Burdens in Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2018;29(5):278-281.

29. Lohman ME, Lio PA. Comparison of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis guidelines-an argument for aggressive atopic dermatitis management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34(6):739-742.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.