- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Aesthetic Treatments Benefit Gender-Diverse Patients

Author(s):

Dermatologists are expanding their skill sets and exploring new techniques to enable gender-diverse patients to achieve their medical and aesthetic goals.

Providing aesthetic procedures such as injectables and hair removal for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) as well as sexual and gender minority (SGM) patients requires more than medical and aesthetic expertise, according to a panel of experts who spoke at the American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX) in April. Serving such patients also demands an understanding of consent and medical insurance issues unique to these populations, they explain.1

Injectable Impetus

Even modest changes in a transgender, or gender transitioning, patients’ self-perception can deliver major quality-of-life (QOL) improvements, said Lauren Meshkov Bonati, MD, a dermatologist in private practice at Mountain Dermatology with offices in Edwards and Frisco, Colorado.2

“It’s important for us to recognize that gender dysphoria is a classified diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5),” Meshkov Bonati said.

Gender dysphoria is categized as a feeling of distress that may occur in those whose gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or sex-related physical characteristics, according to Mayo Clinic.3

Additionally, anywhere from 700,000 to 1.4 million Americans self-identify as transgender, she added.

As with any patient community, caring for LGBTQ+/SGM patients requires an understanding of that population’s holistic needs. Dermatologists should be cognizant of the fact that suicide rates among transgender individuals greatly outpace those in the general population—41% vs 4.6%, respectively—and that QOL improves for transgender people who have undergone transition, Meshkov Bonati said.4

“What does that mean for a dermatologist who’s not performing these types of surgeries?” she asked. “We know that there are approaches that we can use to help the patient achieve a more masculine or feminine appearance. We as cosmetic dermatologists can employ an injectable strategy that will enhance masculine or feminine features for the purpose of helping relieve the gender incongruity that transgender patients feel.”

To explore the QOL impact of injectable treatments in transgender individuals, Meshkov Bonati and colleagues undertook a pilot trial involving 9 patients who had not previously undergone injectable treatments. The trial used a metric called the Gender Continuum Self-Perception Scale, which enabled patients to pinpoint their gender self-perception before and after treatment compared to societal male and female ideals.5

“Subjects overall desired to look from 65% to 100% more masculine or feminine than they did at the moment,” she said.4 “However, 8 of 9 patients said they would be happy looking equally or even less gendered than what they considered society’s ideal.”

These patients were realistic in her view, she continued. “They didn’t have wild expectations of having a brand-new forehead or jawline,” said Meshkov Bonati. “They understood that injectables can’t accomplish the dramatic results that can be achieved with surgery. So we shouldn’t be afraid to treat these patients.”

Posttreatment, patients achieved an average 44% shift toward gender ideals. Three patients flipped their gender perception completely from male to female or vice versa. Global Aesthetic Improvement Scale and Dermatology Life Quality Index results mirrored these findings. “Most patients reported reduced self-consciousness and embarrassment,” Meshkov Bonati said.

Even more telling were the patients’ comments, she added. For example, one subject reported that friends noticed they were posting more frequently on social media. Other patients reported feeling more comfortable in gender-specific clothing and hairstyles. “One patient said, ‘I’m not sure if it’s the treatment itself or just knowing that I’m doing something that makes a difference.’ That’s what this is all about: empowering transgender individuals so that they feel more in control of their gender and how they’re feeling, improving quality of life, and reducing suicidality.”

Because World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) standards of care6 fail to address noninvasive or reversible gender-affirming procedures, a recent paper by Waldman et al recommends establishing such standards, particularly for transgender teens.7 “It’s an open field out there,” Meshkov Bonati said. And dermatologists have the opportunity to set such standards, which may include allowing mature teens to consent to reversible procedures, she adds.

Untreated gender dysphoria may lead to anxiety and depression that persist throughout adulthood, Meshkov Bonati noted. “That’s a huge burden of disease that could potentially be prevented.”

Accordingly, she said injectable interventions for transgender patients should not be viewed as cosmetic. “This isn’t the 65-year-old woman who comes in complaining of marionette lines or brown spots on her face. These are individuals who very deeply know that they are in the wrong body,” Meshkov Bonati said.

With this in mind, she said injectable treatments are crucial to patient dignity. “It’s medically necessary, ethical care that will help adolescents affirm who they are,” Meshkov Bonati added. If dermatologists do not provide safe, ethical, accessible care, she cautioned that transgender patients will seek treatment elsewhere, sometimes with disastrous results.

One day, minimally invasive aesthetic treatments might be considered part of the pretreatment regimen required before gender-reassignment surgery, she said, adding, “Perhaps injectables are something we can use as a way to help the patient dip their toe in and see how it feels to start transitioning physically.”

Hair Removal

As insurers’ willingness to cover hair removal for transgender patients grows, so will dermatologists’ role in securing coverage, said Erica D. Dommasch, MD, MPH,7 a dermatologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts.

In a study coauthored by Dommasch, 4.6% of 174 policies analyzed covered permanent hair removal without restrictions. According to the authors, the remaining 166 policies (95.4%) broadly excluded or did not mention gender-affirming care; prohibited coverage of hair removal or did not mention it; or only permitted coverage of hair removal preoperatively for genital surgery. Dommasch reported that 26% covered only preoperative hair removal for genital surgery; and 28.7% had no policies regarding transgender hair removal.8

The ACA marketplace policies in states without transgender care protections were less likely to cover hair removal without restrictions than ACA policies in states with protections—2 of 85 policies (2.4%) in states without transgender care protections vs 5 of 38 policies (13.2%) in states with transgender care protections, and Medicaid policies were less likely to cover preoperative or nonsurgical hair removal compared with ACA policies—6 of 51 Medicaid policies (11.8%) vs 47 of 123 ACA policies (38.2%).

“Anecdotally, [insurance] coverage seems to be getting a little better over time,” she said. “Many insurance plans will cover permanent hair removal preoperatively, especially if they are covering the gender-affirming surgery.” Some insurers may occasionally cover hair removal in aesthetic areas such as the face, added Dommasch, who also works part time at Fenway Health, a Boston-based community health center that specifically serves the LGBTQ+ community.

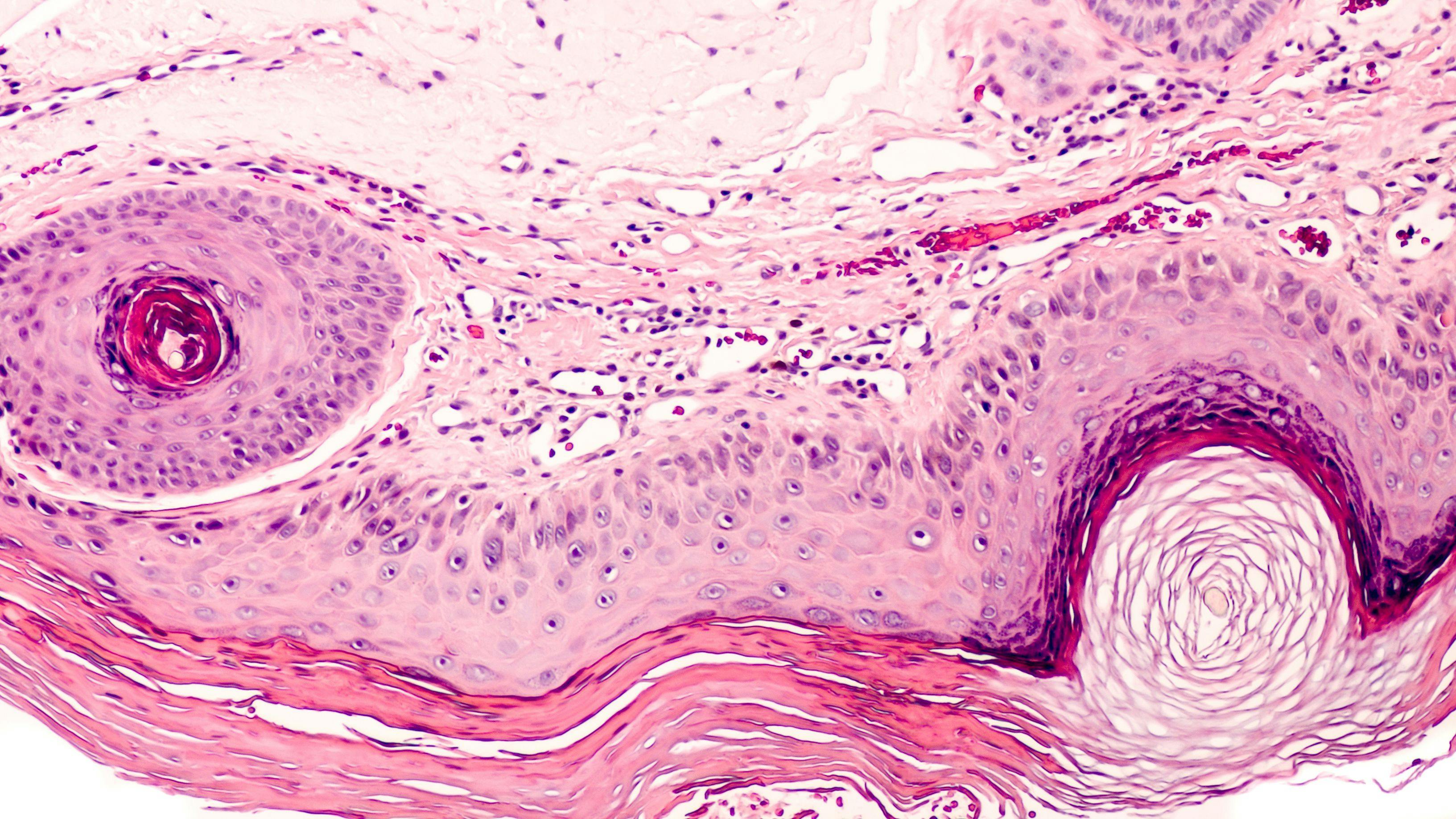

Laser hair removal (LHR) is FDA-approved for permanent hair reduction. Additionally, electrolysis is approved for hair removal because it reduces the number of hair follicles. The FDA’s distinction between permanent hair reduction and removal does not mean that electrolysis is more effective than laser hair removal, said Dommasch. “In fact, probably the contrary is true.”

Many transgender patients require presurgical hair removal to prevent complications such as urinary retention and infections after gender-affirming surgery (GAS). Phalloplasty, the most common type of GAS used in transmasculine patients, involves creating a neophallus using skin flaps from the medial forearm or anterolateral thigh, both of which may need presurgical hair removal.8

Creating a neovagina for transfeminine patients typically involves skin from the penile shaft or scrotum, the latter of which typically requires hair removal. “Areas of the scrotum that may be treated include either the midline, if using a pedicled scrotal flap, or entire scrotum, for free scrotal skin full-thickness grafts,” Dommasch said.

Because patients typically require 6 to 12 months of hair removal before undergoing GAS, she advised that it is crucial for dermatologists to confirm with patients and surgeons which genital areas and donor sites require treatment long before surgery. “This can be done via photos or permanent ink markings of the sites. Keep in mind that the surgeon may want more than one site treated—they may want both forearms or legs treated,” she said.9

In a recent study, 56% of patients undergoing phalloplasty consults had forearm tattoos.10 If patients choose skin flaps from tattooed areas, that means the neophallus is going to have a tattoo,” Dommasch explained. Additionally, tattoos can interfere with LHR. “If patients choose to use the forearm site, and they have a tattoo, these patients may need electrolysis for these areas.”

Dermatologists serving transgender patients must know that securing prior authorizations (PAs) for hair removal will be time-consuming and may require dedicated staff, she said. “Keep trying,” she said. “These policies are continually changing. Insurers are very confused about what they should and should not cover in the context of gender-affirmation surgeries.”

Accordingly, Dommasch recommended becoming familiar with policies of the most common private insurers in the practice’s area—especially Medicaid—and creating templated PA letters tailored to each insurer. Where possible, these letters should mirror language used in specific policies. She added that before covering presurgical hair removal, many insurers require documenting that patients have met all applicable WPATH criteria,11 which are extensive.

Regarding billing, she suggested having a price list available for all potential hair removal sites. “Many insurers will pay a standard percentage of the asking price,” Dommasch said, while also recommending tracking reimbursement rates so that one can set prices commensurately. “Remember, if you increase your price for these patients, you may be increasing the price for patients who pay out of pocket,” she said. Dermatologists may bill permanent hair removal with CPT code 17999, unlisted skin procedure, which has no standard negotiated price.

“Looking forward, dermatologists are going to be very important in ensuring affordable, safe access to hair removal,” Dommasch said. “We need to work closely with policy makers, insurance companies, and other stakeholders. Hopefully, down the road we will get designated CPT codes for these gender-affirming procedures, and hair removal as well, which will make everyone’s life easier.”

Disclosures:

Meshkov Bonati’s study was funded by Allergan. Dommasch reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

References:

1. Peebles JK, Dommasch ED, Meshkov Meshkov Bonati L, et al. LGBTQ/SGM health in dermatology: updates & pearls in a changing landscape. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX), April 23-25, 2021. Virtual.

2. Meshkov Bonati LM. Gender-affirming procedures: injectables. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience. April 23-25, 2021. Virtual.

3. Gender dysphoria. Mayo Clinic. December 6, 2019. Accessed June 15, 2021. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/gender-dysphoria/symptoms-causes/syc-20475255

4. Herman JL, Haas AP, Rodgers PL. Suicide attempts among transgender and gender non-conforming adults. American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. 2014. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8xg8061f

5. Meshkov Bonati L, Petrell K, MacGregor J, Kandula P, Dover JS, Kaminer MS. The effects of neurotoxin and soft tissue fillers on gender perception in transgender individuals: a pilot prospective survey-based study. Published online March 5, 2021. J Am Acad Dermatol. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.080

6. World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-conforming people. 7th version. 2012. Accessed May 26, 2021. https://www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/SOC%20v7/SOC%20V7_English2012.pdf?_t=1613669341

7. Waldman RA, Waldman SD, Grant-Kels JM. The ethics of performing noninvasive, reversible gender-affirming procedures on transgender adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(6):1166-1168. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.052

8. Dommasch E. Hair removal: review and updates in transgender health. Presented at: American Academy of Dermatology 2021 Virtual Meeting Experience (AAD VMX). April 23-25, 2021.

9. Thoreson N, Marks DH, Peebles JK, King DS, Dommasch E. Health insurance coverage of permanent hair removal in transgender and gender-minority patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(5):561-565. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0480

10. Zhang WR, Garrett GL, Arron ST, Garcia MM. Laser hair removal for genital gender affirming surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(3):381-387. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.03.27

11. Benson TA, Boskey ER, Ganor O. The effect of forearm tattoos on flap choice in transmasculine phalloplasty patients. MDM Policy Pract. 2020;5(1):2381468320938740. doi:10.1177/2381468320938740

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.