- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

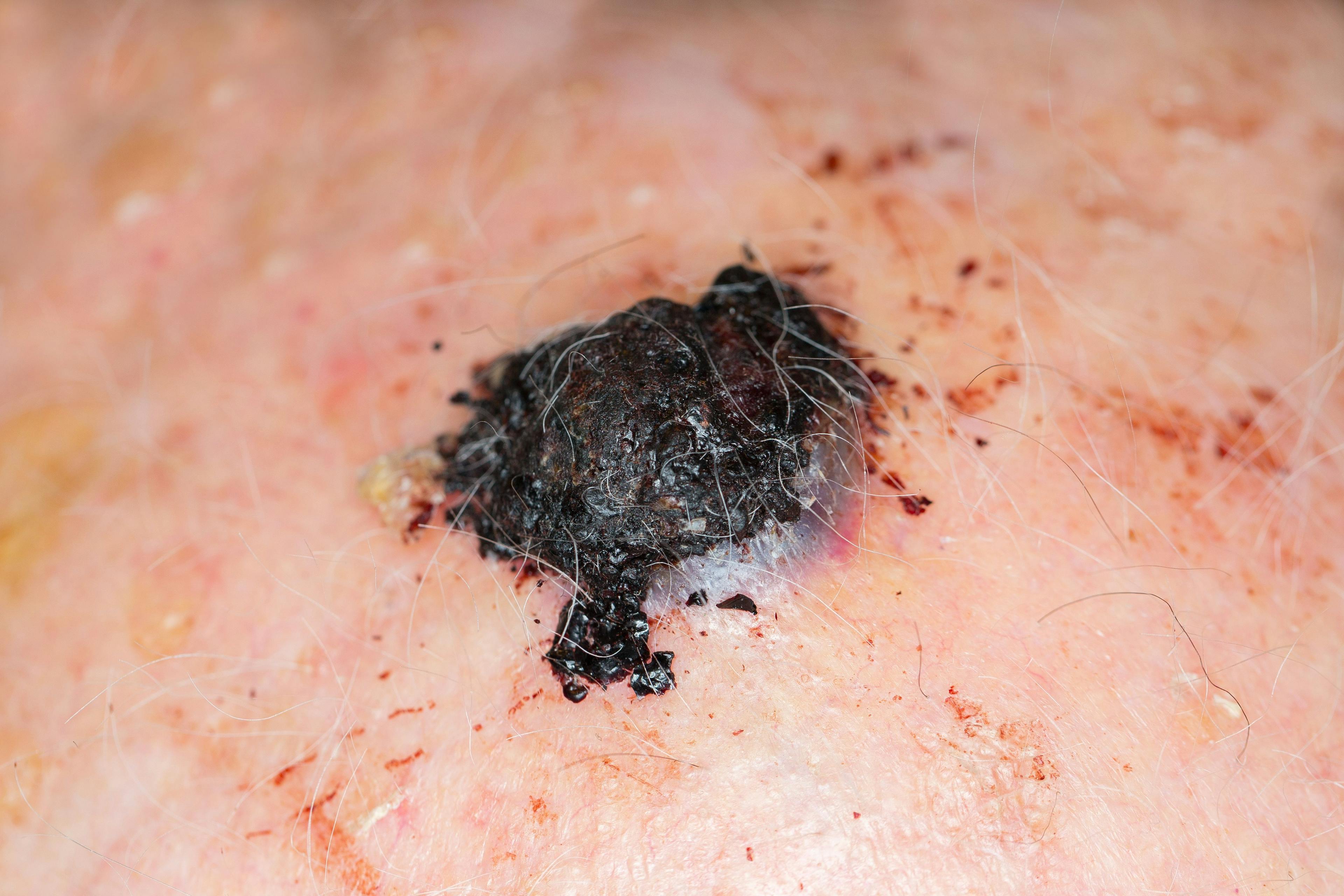

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Study examines port-wine stain treatment in infants

Author(s):

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) is widely accepted as the gold standard treatment of port-wine stains (PWS), but how early can you begin treating infants with PWS? According to this expert and a recent study, the sooner the better.

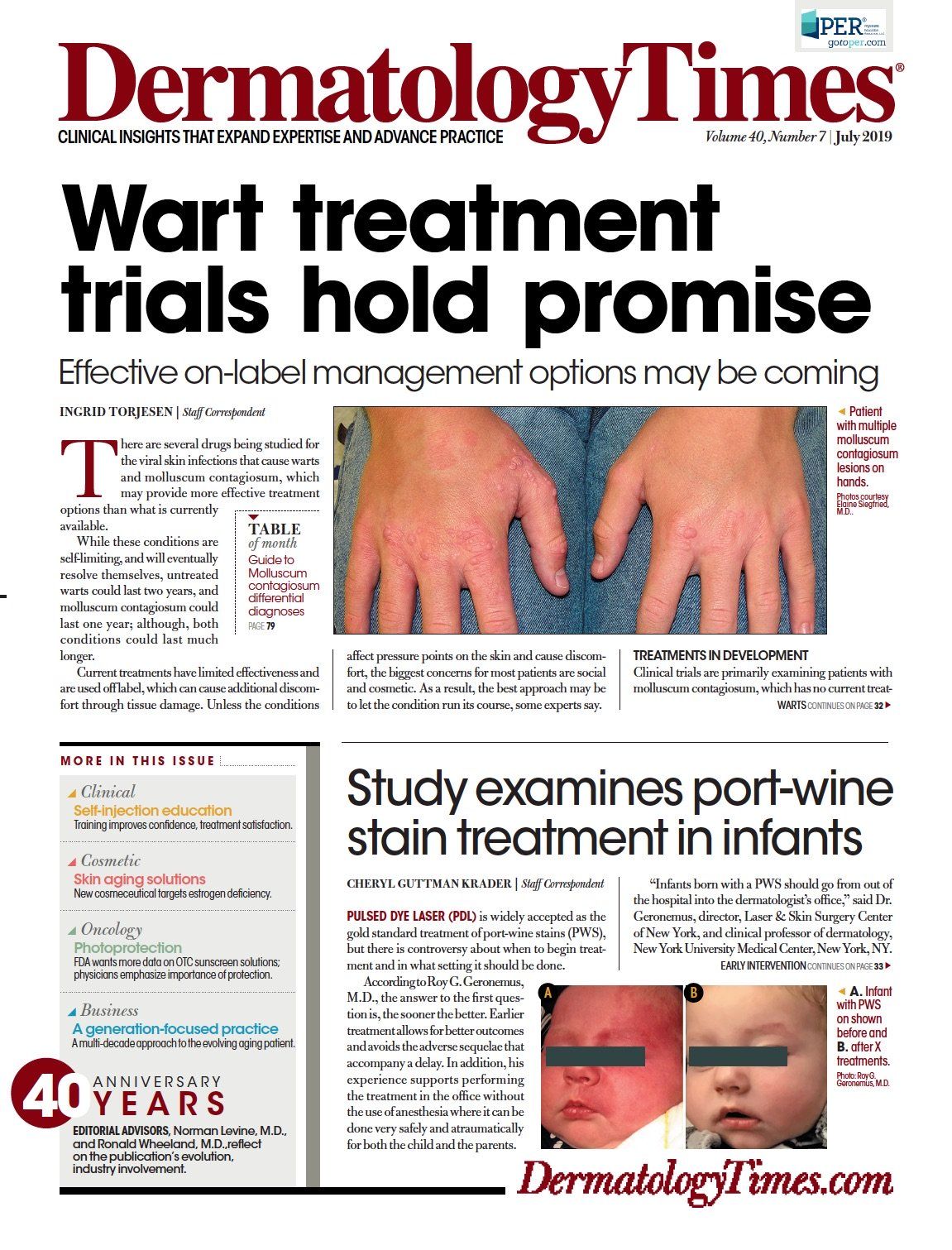

A. One-month-old infant with port-wine stain shown before and B. at 8 months old after eight treatments with Vbeam Perfecta Laser. (Photo courtesy of Roy G. Geronemus, M.D.)

Dr. Geronemus

Pulsed dye laser (PDL) is widely accepted as the gold standard treatment of port-wine stains (PWS), but there is controversy about when to begin treatment and in what setting it should be done.

According to Roy G. Geronemus, M.D., the answer to the first question is, the sooner the better. Earlier treatment allows for better outcomes and avoids the adverse sequelae that accompany a delay. In addition, his experience supports performing the treatment in the office without the use of anesthesia where it can be done very safely and atraumatically for both the child and the parents.

“Infants born with a PWS should go from out of the hospital into the dermatologist’s office,” said Dr. Geronemus, director, Laser & Skin Surgery Center of New York, and clinical professor of dermatology, New York University Medical Center, New York, NY.

“Parents whose babies have a disfiguring PWS are anxious for options that can eliminate the lesion, and dermatologists who treat PWS need to make the effort to accommodate these families in their appointment schedule. We also need to educate our colleagues in pediatrics about the benefits and safety of early treatment so that they will make the referral.”

ARGUMENTS FOR EARLY INTERVENTION

One of the reasons that favor early initiation of PDL treatment is that it is likely to afford the best outcome.

“Anecdotal evidence shows that the response to PDL is better when the treatment is done in younger versus older children. Earlier treatment results in more complete clearing and requires fewer sessions,” Dr. Geronemus says.

There are several explanations for the better results in younger children. Penetration of the laser energy to its target – the hemoglobin in the PWS capillaries – is better because babies have thinner skin. In addition, the natural history of PWS is that they thicken, darken, and become larger as the child grows, and these features also make clearance more challenging.

Treatment in infancy also enables performance without general anesthesia because it is easier to hold and immobilize a baby than it is an older child.

In addition, as the PWS changes from a flat patch to a thicker plaque, it is at risk for bleeding secondary to physical trauma. There are also psychosocial consequences of delaying treatment that should be considered.

“There is documented evidence that children with a PWS on the face or another cosmetically visible area recognize they are different from their peers and have increased emotional stress and diminished self-esteem,” Dr. Geronemus says.

OFFICE VS. OR

Advocates of performing the PDL treatment in a hospital setting under general anesthesia cite concerns over comfort and the need for the child to remain still. However, treatment in the hospital carries a number of drawbacks, Dr. Geronemus explains.

“Treatment in an OR using general anesthesia is expensive, time consuming, not accessible for all physicians, and poses a risk for fire due to the interaction between the laser and oxygen and nitrous oxide that are present in the OR,” he says.

“Furthermore, general anesthesia has its own safety risks, and in 2016, the FDA issued a warning that repeated or lengthy use of general anesthetic and sedation drugs in children younger than three years may affect brain development.1”

SUPPORTING EVIDENCE

In a paper published in JAMA Dermatology online in March 2019, Dr. Geronemus and colleagues reported their very positive findings from a retrospective cohort study of in-office PDL PWS treatment without general or topical anesthesia in children aged ≤1 year.2 Medical record review identified 197 patients who were treated between 2000 and 2017, and data were extracted for outcomes at 1 year after treatment initiation.

The population was comprised of 73 (37%) boys and 124 (63%) girls. About three-fourths of the children were treated for a facial lesion, and the mean age of first treatment was 3.4 months. The earliest treatment was performed in a child who was just five days old.

Mean PWS size was 61 cm2 with a range from 0.49 to 600 cm2. On average, the children underwent 10 treatments, but the range was from two to 23.

There were no cases of scarring or permanent pigmentary changes. Improvement in PWS was rated by four independent physicians who used a 5-point visual analog scale to compare before and after photographs. According to their assessments, approximately one-fourth of the lesions achieved total clearance, and 41% showed 76% to 99% improvement. In 22% of children, the PWS improved by 51% to 75%, 6.6% had 26% to 50% improvement, and 4.1% of the lesions had ≤25% improvement.

“Whether looking at all lesions, those on the face, or nonfacial PWS, the mean VAS grade was 3.65, which corresponds to excellent clearance,” Dr. Geronemus says.

Lesions that achieved complete clearance had a smaller average size and required fewer treatments compared with those that had less improvement. Analyses of outcomes based on anatomic location showed that the best results were obtained when treating lesions on the first branch of the trigeminal nerve.

“Lesions below the elbows and below the knees can be difficult to treat, and families are informed about the potential for less improvement if the child’s PWS is in one of those locations. Our experience shows that regardless of location, it is possible to get a very good result. However, there are also no guarantees,” Dr. Geronemus says.

He adds that while the study lacks long-term follow-up, his experience indicates that the better the initial result, the lower the chance of recurrence.

“Most of the recurrences I have seen are in patients who did not have a significant response to initial treatment or who were not fully treated. I have seen many patients who had excellent results initially and still look good after 10 to 15 years,” Dr. Geronemus says.

LOGISTICS

In-office treatment without anesthesia requires a team to immobilize the child, and metal corneal shields should be placed to protect the eyes when treating a lesion involving the periocular region.

“Some physicians may not feel comfortable about inserting the shields, but it is done after application of an ophthalmic anesthetic solution and can be done safely and quickly with just a little experience,” Dr. Geronemus says.

Ideally, children return for sessions every two to three weeks, although the interval between treatments is extended in children with darker skin. This frequent repeat schedule seems to accelerate the response and therefore minimize the total number of treatments needed, according to Dr. Geronemus.

The treatment is performed using dynamic cooling that minimizes discomfort and with a large spot size (typically 10-mm for face and neck lesions and 12-mm for body PWS) that allows for a shorter treatment session. Â

Disclosures:

Dr. Geronemus is an investigator for and on the medical advisory board for Candela

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.