- Case-Based Roundtable

- General Dermatology

- Eczema

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Alopecia

- Aesthetics

- Vitiligo

- COVID-19

- Actinic Keratosis

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Rare Disease

- Wound Care

- Rosacea

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Skin Cancer

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Drug Watch

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Acne

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Practice Management

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Buy-and-Bill

Article

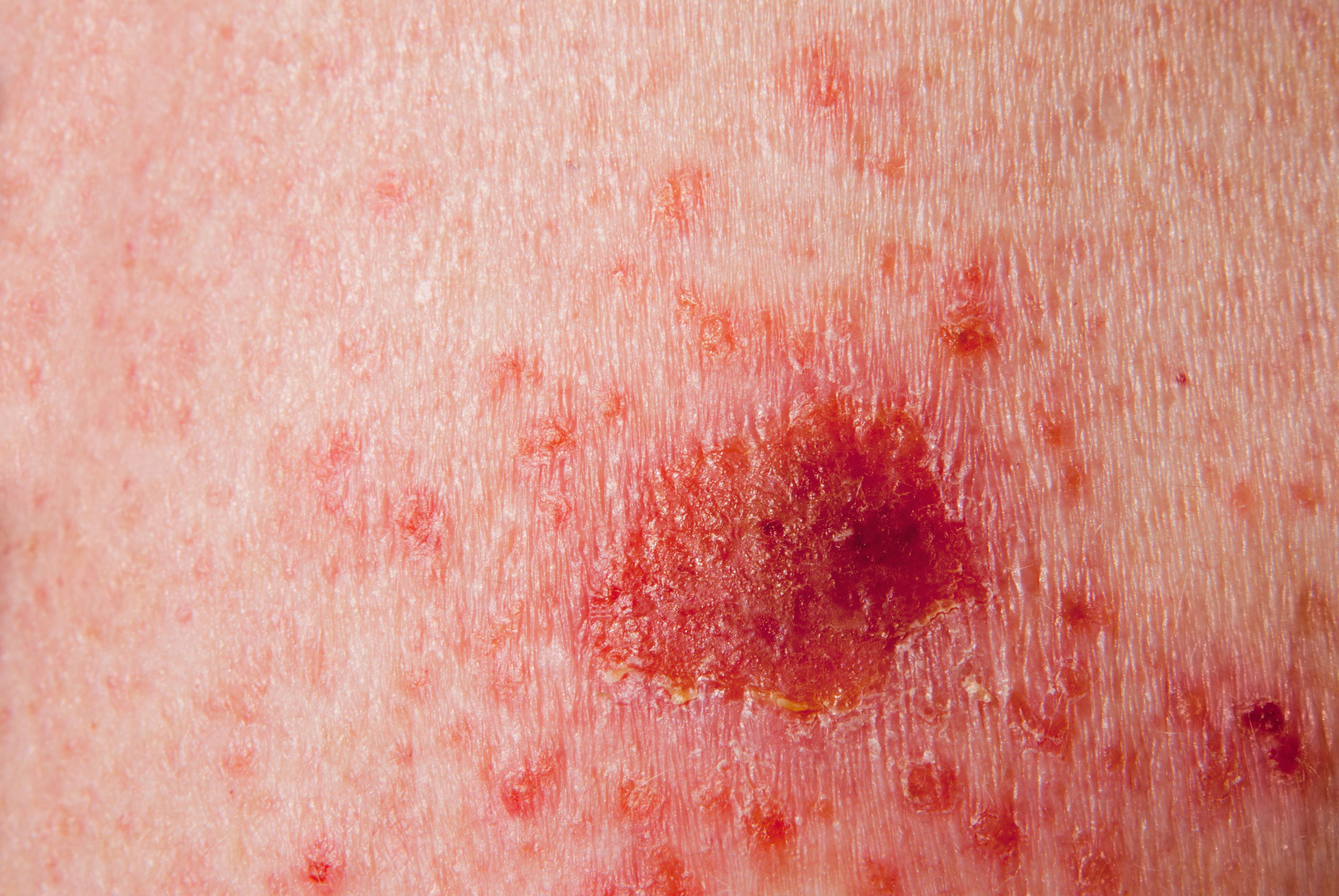

German basal cell carcinoma guidelines strengthen global consensus

Author(s):

New German basal cell carcinoma (BCC) guidelines are more alike than unlike U.S. guidelines, although minor differences exist in areas such as prevention and newer systemic treatments, says experts.

“The two guidelines are almost interchangeable. This suggests a strong international consensus regarding the management of BCC,” says Murad Alam, M.D. (Laura Ballard - stock.adobe.com)

New German basal cell carcinoma (BCC) guidelines are more alike than unlike U.S. guidelines, sources say, although minor differences exist in areas such as prevention and newer systemic treatments.

RELATED: Genetic expression profiling for squamous cell carcinoma

Coordinated by Stephan Grabbe, M.D., of the department of dermatology, Mainz University Medical Center in Mainz,

Germany, the guidelines were published in the February 2019 edition of the Journal of the German Society of Dermatology.1

Murad Alam, M.D., says the German guidelines and American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) BCC guidelines published in the January 2018 Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology2 are remarkably similar.

“In terms of diagnosis, therapies, risk stratification, discussion of special cases and even terminology, the two guidelines are almost interchangeable. This suggests a strong international consensus regarding the management of BCC,” Dr. Alam says. He is vice chair of dermatology and professor of dermatology, otolaryngology and surgery at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago. He also cochaired the AAD BCC guidelines committee.

For starters, both guideline sets stratify BCCs according to size and location, with lesions in the so-called H zone carrying the highest recurrence risk. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network defines this zone as the central face, eyelids, eyebrows, periorbital skin, nose, lips, chin, mandible, preauricular and post-auricular skin/sulci, temple, ear, genitalia, hands and feet.3

Likewise, German and AAD guidelines recommend surgical excision with histological margin control as the treatment with the lowest recurrence rates for low-risk primary BCC. Topical treatments such as imiquimod, 5-fluorouracil and photodynamic therapy are reserved for small, superficial BCCs, primarily in patients with contraindications for surgery. The same holds true for cryosurgery and lasers.

RELATED: Skin cancer imaging device speeds diagnosis

With low-risk BCC, German guidelines recommend 3 mm to 5 mm standard surgical margins, while the AAD recommends 4 mm. This numerical discrepancy is a distinction without a difference, say Drs. Alam and Daniel B. Eisen, M.D. Dr. Eisen is director of dermatologic surgery at the University of California, Davis School of Medicine and an AAD guidelines co-author.

“For low-risk BCC,” says Dr. Alam, “4 mm is virtually the same as 3 to 5 mm.” With the increased availability of margin- controlled techniques such as Mohs surgery in the United States, he says, very large standard surgical margins (up to 15 mm for standard excision of high-risk BCCs in the German guidelines) are rarely needed for high-risk BCCs stateside.

Dr. Eisen says he believes that 4 mm is safer than 3 mm because in his anecdotal experience, a 3-mm cutoff produces more positive margins and repeat procedures than he’d like. Nevertheless, he says, 3 mm is reasonable for low-risk lesions given the fact that no randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) compare margins of 3, 4 or 5 mm against each other in BCC.

“All we’ve got is cohort studies, and often you just get a range - ‘Authors used a margin of 3-5 mm.’ So you can’t draw firm conclusions based on that,” he says.

Additionally, both guidelines recommend Mohs surgery for high-risk lesions. Furthermore, AAD guidelines include several additional paragraphs’ discussion of appropriate Mohs use that are not in the German guidelines. “Mohs is more available in the United States,” Dr. Alam says. “So, it is useful to have appropriate use criteria for Mohs here. I suspect as Mohs becomes more available in Germany and other countries, similar guidance will be considered there.”

RELATED: Imaging evolves to guide Mohs surgery

It’s also important to remember, he adds, that although payers sometimes wish to restrict access to Mohs surgery, widespread availability of the technique brings many patient benefits.

“In particular, tumors are treated when they are smaller and more easily surgically resectable without morbidity, disfigurement and functional loss,” he says.

The AAD and its members expended significant effort to produce the appropriate-use criteria, adds Dr. Eisen, and any discussion of U.S. BCC guidelines would have been remiss not to mention them.

IMMUNE CHECKPOINT INHIBITORS

Among newer systemic BCC treatments, German and American guidelines recommend the hedgehog inhibitors vismodegib and sonidegib for metastatic and locally advanced BCC (including, for the AAD, patients with nevoid BCC/Gorlin syndrome). Both German and American guidelines also note the substantial toxicity of long-term vismodegib therapy - in a phase 2 study, only 3 of 18 eligible patients could tolerate continuous vismodegib for 36 months.4 Accordingly, say the German guidelines, intermittent therapy appears appropriate in high-risk patients.

The German guidelines add that due to their high mutation load, BCCs are good candidates for immune therapy with checkpoint inhibitors, specifically anti-PD1 inhibitors, one of which (cemiplimab, NCT 03132636) was undergoing phase 2 study in Germany at press time. In a companion document covering BCC epidemiology, genetics and diagnosis, the German authors write, “Activation of the sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling pathway plays a key role in the development of BCCs.” A mutation in the SHH inhibitor patched (PTCH) causes uncontrolled activation of smoothened (SMO), rendering keratinocytes resistant to apoptosis.5

RELATED: Genetic insights improve tumor classification

Conversely, the AAD guidelines do not mention checkpoint inhibitors, largely because their track record in BCC stateside is relatively brief, say Drs. Alam and Eisen. “While PD-1 inhibitors are kept in reserve in case of failure of hedgehog inhibitors,” says Dr. Alam, “we have not used these drugs for many years in many patients with different types of BCC. The AAD guidelines approach is thus a more conservative interpretation that reserves judgment and avoids a strong recommendation due to the limited U.S. experience with this class of drugs for BCC.”

Dr. Eisen adds, “At the time we crafted our guidelines, I don’t remember seeing any randomized, controlled trials on the use of PD-1 inhibitors for BCC. The number of people who would benefit from them is likely to be pretty low, because not many people have metastatic BCC. So it’s not a huge issue for us yet.” Medications with proven efficacy for metastatic or locally advanced BCC should be recommended before second-line treatments, he says, and both vismodegib and sonidegib have randomized trials showing that they produce a response in patients who are not appropriate for surgery or have metastatic disease.

NICOTINAMIDE

Regarding BCC prevention, German guidelines strongly recommend oral nicotinamide (500 mg twice daily), particularly for secondary prevention in patients with pre-existing BCC. In a large Australian RCT involving 386 patients with a history of multiple BCCs, this regimen reduced the risk of developing BCCs 20% (p=0.12).6

However, AAD guidelines state there is insufficient evidence to make a recommendation about the use of nicotinamide. The 20% reduction in the above study did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12), Dr. Eisen explains. “Additionally, there was only one randomized trial regarding the use of nicotinomide to prevent BCCs. To make firm conclusions one would like to see multiple trials performed at different centers, each demonstrating efficacy.”

Furthermore, AAD guidelines note, the purported benefits of nicotinomide use were lost soon after discontinuation of the medication. “Thus patients would need to be on the medication indefinitely to continue to see risk reductions from its use,” Dr. Eisen says.

RELATED: Imaging techniques advance skin cancer management

Dr. Alam adds that creating guidelines often requires judgment calls. “Sometimes the answer is not clear, and both a qualified recommendation or no recommendation are reasonable options. Such is the case for nicotinamide, for which the supportive arguments rest primarily on one high-quality randomized controlled trial.”

Given the limited evidence, he says, both the German and U.S. recommendations regarding nicotinamide are reasonable. “As long as the guidelines cite the relevant data in such situations, clinicians can decide for themselves, given specific patient and tumor factors.”

Overall, adds Dr. Alam, it’s helpful for guideline writers and policymakers to familiarize themselves with guidelines written by different organizations from different countries. “We learn from each other, and we can improve. Also, we are reassured when we find that we’re in agreement, and the few dissimilarities are modest or cosmetic.”Â

References:

1. Lang BM, Balermpas P, Bauer A, et al. S2k guidelines for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma-part two: treatment, prevention and follow-up. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:214-230.

2. Bichakjian C, Armstrong A, Baum C, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:540-559.

3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: basal cell skin cancer. Version 1.2019. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nmsc.pdf. Published August 31, 2018. Accessed September 27, 2019.

4. Tang JY, Ally MS, Chanana AM, et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in patients with basal-cells nevus syndrome: final results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:1720-1731.

5. Lang BM, Balermpas P, Bauer A, et al. S2k guidelines for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma-part one: epidemiology, genetics and diagnosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2019;17:94-103.

6. Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin-cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.