- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

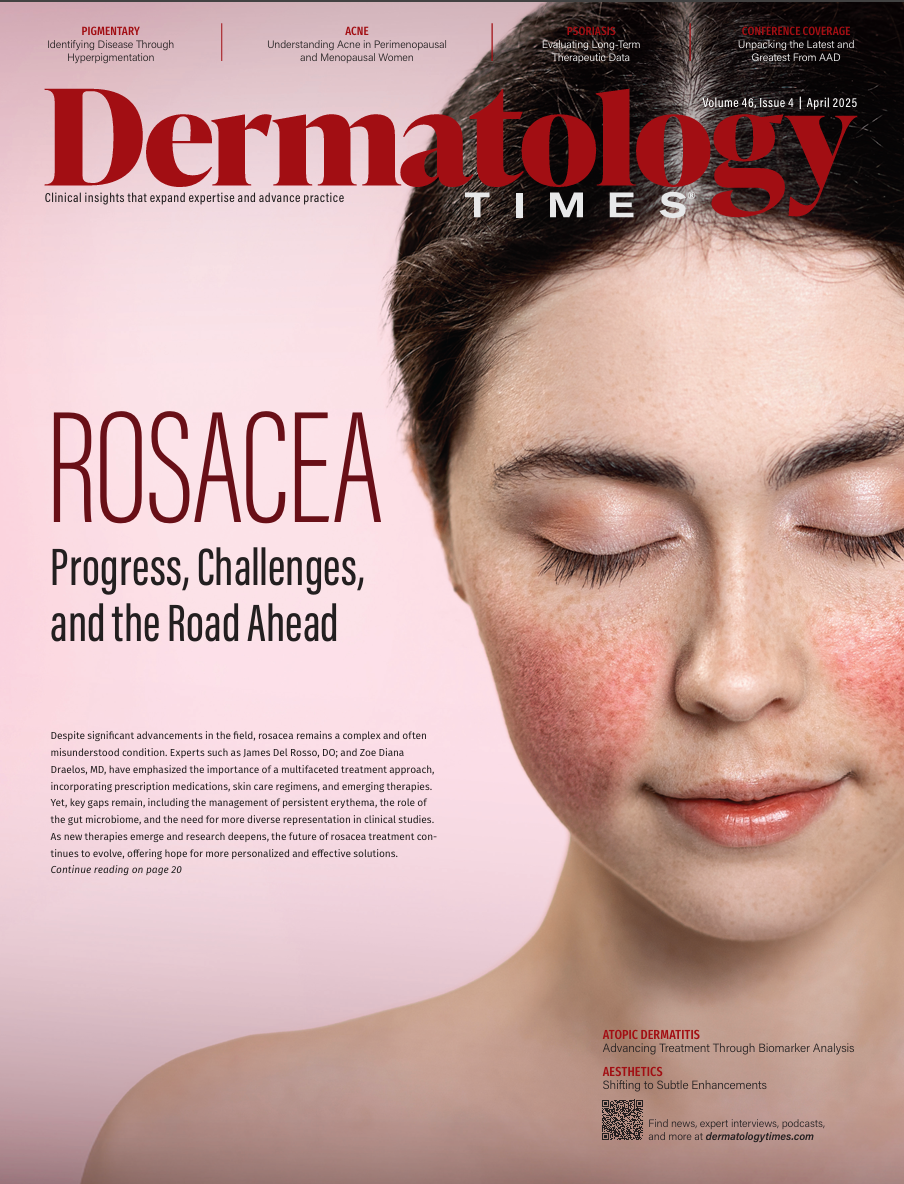

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Beyond Melasma: Systemic Causes of Facial Hyperpigmentation

Author(s):

Key Takeaways

- Lichen planus pigmentosus and vitiligo significantly affect patients' quality of life, more so than melasma.

- Maturational hyperpigmentation is often misdiagnosed as melasma but is linked to obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.

Facial hyperpigmentation may signal systemic disease. Dermatologists must assess beyond melasma to ensure timely, accurate diagnosis and care.

Due to the frequent involvement of pigmentary disorders of the face, dermatologists must be aware of their significant impact on patients’ quality of life. As these conditions remain one of the most common reasons to seek dermatologic care, concerns of physical appearance, social well-being, and financial stability are top-of-mind for patients.

Image Credit: © toa555 - stock.adobe.com

In a comparative analysis of lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP), vitiligo, and melasma, over half of patients with LPP and vitiligo reported significant or very significant disease-related effects on their quality of life. In contrast, melasma had a somewhat lesser impact in this regard.1

It is crucial for dermatology providers to be aware of the potential systemic causes of facial hyperpigmentation. When encountering a patient with facial hyperpigmentation, clinicians must look beyond common conditions like melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, as an undiagnosed systemic disease may be contributing to the presentation.

Maturational Hyperpigmentation

One such condition is maturational hyperpigmentation, which often manifests as hyperpigmented, polygonal thin plaques with a rough, grainy texture, typically located on the zygomatic cheeks and temples. This can be frequently misdiagnosed as melasma; however, maturational hyperpigmentation differs morphologically and is often associated with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus. Some researchers have suggested that maturational hyperpigmentation may lie on the spectrum of facial acanthosis nigricans, as the conditions share similar comorbidities.2 However, others argue they are distinct.2 Key differences between the 2 include histological characteristics and dermoscopic findings. In maturational hyperpigmentation, there is minimal hyperkeratosis, slight papillomatosis, and mild to moderate proliferation of the basal cell layer—features not seen in acanthosis nigricans.

Treatment of Maturational Hyperpigmentation

Treatment typically includes a modified Kligman formulation, topical retinoids, glycolic acid or trichloroacetic acid chemical peels, keratolytics, and sun protection. Dermatologists should also collaborate with primary care providers to screen for associated comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

Renal Disease and Hyperpigmentation

Cutaneous manifestations of renal disease are not uncommon. While pruritus, xerosis, and Kyrle disease are frequently observed in patients with end-stage renal disease, hyperpigmentation is less commonly reported. Kolla et al found that 40% of patients undergoing hemodialysis at least twice weekly for 3 months experienced diffuse hyperpigmentation, which was most pronounced in sun-exposed areas.3 The authors suggest that the hyperpigmentation results from the kidneys’ failure to excrete melanocyte-stimulating hormone, leading to increased melanin production in both the epidermis and dermis.

Liver Disease and Hyperpigmentation

Chronic liver disease is another systemic condition that can cause characteristic cutaneous changes. Most clinicians are familiar with pruritus, jaundice, and the matted telangiectasias that occur with liver disease, but a recent study of 110 patients from a tertiary care hospital in India found that facial hyperpigmentation was present in 49% of patients.4 This pigmentation, often muddy brown or gray, typically affects the periocular and perioral areas and, in advanced cases, can extend to the extremities.

Histopathological examination shows increased melanin in both the epidermis and dermis, unlike the pigmentation observed in hemochromatosis, where iron stains are typically positive. The cytotoxic effects of bile salts may activate tyrosinase, leading to pigmentation. Notably, hyperpigmentation can occur early in the course of liver disease and during acute episodes, making it an important clue for earlier diagnosis.

Medications and Hyperpigmentation

Medications account for approximately 20% of acquired cases of hyperpigmentation.5 Mechanisms include the accumulation of melanin, the drug itself, the synthesis of new pigments, and dermal iron deposition. Drug-induced hyperpigmentation often worsens over months to years, and the distribution may vary depending on the drug, although sun-exposed areas are commonly affected. Medications associated with facial hyperpigmentation include chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, amiodarone, amitriptyline, diltiazem, isoniazid, bimatoprost, chemotherapeutic agents, minocycline, and phenytoin. Since improvement may or may not occur upon discontinuation of the drug, early recognition is crucial.

Conclusion

It is essential for dermatologists to keep a broad differential diagnosis in mind when evaluating facial hyperpigmentation, as it may indicate underlying systemic conditions such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, alcoholic liver disease, and end-stage renal disease. A thorough patient history, review of medications, and comprehensive clinical examination are critical for timely diagnosis and intervention, preventing further complications.

References

- Gupta V, Yadav D, Satapathy S, et al. Psychosocial burden of lichen planus pigmentosus is similar to vitiligo, but greater than melasma: a cross-sectional study from a tertiary-care center in north India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:341-7. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_877_19

- Goyal P, Chauhan P. Maturational hyperpigmentation: an update. Cosmo Derma. 2024;4:23. doi:10.25259/CSDM_269_2023

- Kolla PK, Desai M, Pathapati RM, et al. Cutaneous manifestations in patients with chronic kidney disease on maintenance hemodialysis. ISRN Dermatol. 2012;2012:679619. doi:10.5402/2012/679619

- Bansal S, Verma P. Study of pigmentary disorders of skin associated with underlying chronic liver disease. Int J Dermatol Venereol Leprol Sci. 2021;4(2, pt A). doi:10.33545/26649411.2021.v4.i2a.83

- Nahhas AF, Braunberger TL, Hamzavi IH. An update on drug-induced pigmentation. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(1):75-96. doi:10.1007/s40257-018-0393-2

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.