- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

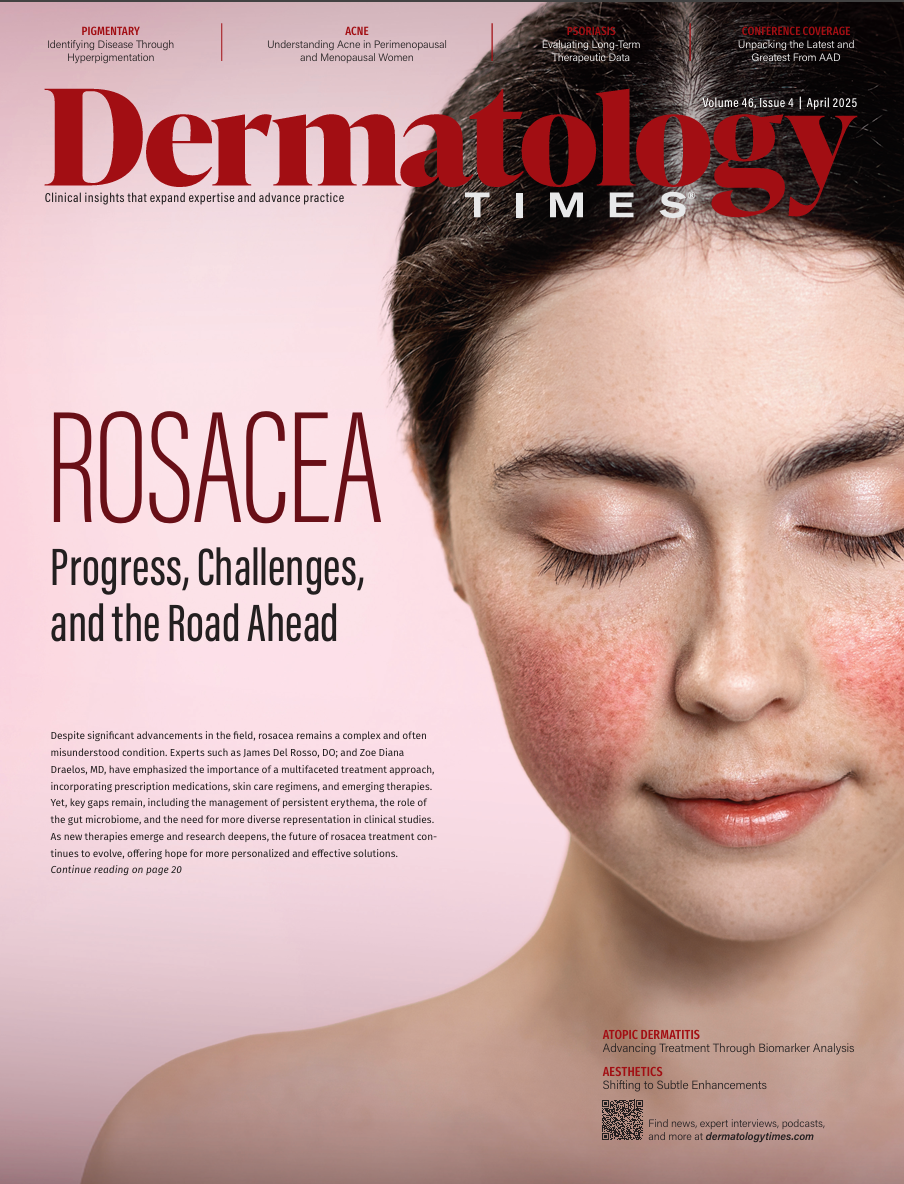

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

How to Best Support Women With Menopausal Acne

Author(s):

Key Takeaways

- Menopausal acne affects 12%-22% of women, causing significant emotional distress and quality of life impact, especially in those with darker skin due to scarring.

- Treatment involves a stepwise approach, starting with gentle skincare and topical agents like salicylic acid, azelaic acid, and retinoids.

Menopausal acne is rising yet underexplored; treatment must address hormonal shifts, skin sensitivity, and patient emotional well-being.

Although perimenopausal and menopausal acne are becoming more common in dermatology clinics each year, it remains an underexplored area of research. Acne in middle-aged to older adult years affects 12% to 22% of women compared with 3% of men,1 and it is reported to have a significantly higher negative effect on women’s quality of life compared with men. Furthermore, acne in patients with darker pigmented skin tends to be more detrimental due to the darker postinflammatory scarring and keloids left behind from the deep inflammation caused by menopausal acne. As opposed to adolescent acne that tends to flare on the cheeks and forehead, menopausal acne typically flares on the chin, mandible, and around the mouth.

Image Credit: © buena17 - stock.adobe.com

Perimenopausal and menopausal acne are reported to cause more emotional distress and anguish than adolescent acne flares, although not quite as common compared with adolescents. This could be caused by the increased expectation and acceptance of adolescent acne during that specific phase of life compared with a middle-aged woman experiencing perimenopausal changes. This emphasizes the importance of understanding patient concerns and offering effective treatment plans.

Treatment options for women who are menopausal or postmenopausal are not quite as streamlined. Although acne has classically been considered a transient, age-targeted skin condition, we are witnessing acne in all stages of life. Acne is now being broken down into 3 categories: persistent acne, recurrent acne, and late-onset acne.2 Persistent acne is seen in adolescents and young adults as a disorder of inflammation of the pilosebaceous unit that is immune mediated and androgen triggered. Recurrent acne is when acne disappears after the “young presentation” but then returns in the same pattern in midlife (30s to 40s). Late-onset acne refers to women who are experiencing the hormonal changes of menopause who experience new onset acne.

Before creating a stepwise treatment plan for late-onset acne in menopausal women, clinicians should collect medical history that focuses on lifestyle. Factors that can worsen acne flares during menopause are lack of sleep, skin manipulation, washing frequency, smoking, and hormonal supplementation such as anabolic steroids and some forms of progestin.3

Pathophysiology Behind Menopausal Acne

When the female body enters the menopausal state (12 consecutive months without a menstruation cycle), there is a steep decline in estrogen. There are many estrogen receptors throughout the female body; however, there is a specifically dense amount in the face, genitals, and legs. During menopause and approximately 5 years post menopause, there is a dramatic decrease in dermal collagen and an increase in elastin degeneration. This combination leads to increased skin laxity and wrinkling.3 There is also increased transepidermal water loss through the decreasing skin barrier function. Due to poor barrier function, the inflammatory cascade that triggers acne is thought to take place.4

Treatment Strategies

Chronic, intermittent flares of acne can occur for years following menopause. It is important to emphasize that adhering to an appropriate skin care routine helps with consistent results. Typically, topical treatment is most effective due to the pathophysiology behind menopausal skin changes.

Step 1

Mature (menopausal/postmenopausal) skin with acne is different from adolescent skin with acne. Mature skin lacks the ample amount of hormones that produce oil and is dry and easily irritated by some of the classic acne treatments. First, discuss the importance of gentle cleansing with a mild cleanser. Only wash the face 1 to 2 times a day to protect the skin barrier, followed by applying a noncomedogenic moisturizer. Caring for the skin barrier will help decrease the amount of irritation from transepidermal water loss. If the patient is interested in an acne cleanser, encourage a 2% salicylic acid wash daily and azelaic acid (20% cream or 15% gel) twice a day.

Benzoyl peroxide (as a 4% wash or in 2.5% cream form) is a great option to introduce a bactericide component into a daily routine. This is an effective intervention due to the very low chance that there could be resistance to the mechanism of action, which consists of introducing oxygen into the follicle.2 This helps prevent both inflammatory and noninflammatory papules. Benzoyl peroxide can be irritating to menopausal and postmenopausal skin; if this happens, consider swapping it out for a 2% salicylic acid wash or azelaic acid 20% cream or 15% gel. Azelaic acid helps to improve pigmentation and express anti-inflammatory components due to the inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis and blockage of Toll-like receptors.2 Additionally, it improves pigmentation by expressing keratinization-normalizing properties. This intervention is safe and well tolerated.

All these options are good to consider for monotherapy in late-onset mild to moderate acne or can be used in combination with topical clindamycin 1% lotion 2 times a day. Of note, topical clindamycin cannot be used as a monotherapy due to the risk of antibiotic resistance.

Step 2

Consider treating the patient with topical dapsone 5% to 7.5% cream (gel can be drying). This works as an anti-inflammatory agent with no known bacterial resistance. It does not have difficult drying adverse effects and is effective as a monotherapy. Due to the tolerability and safety with almost no adverse effects, adherence is likely.

Step 3

Consider adding a retinoid, as these increase keratinocyte turnover, which decreases pore size, fine lines, and wrinkles, and helps to prevent the blockage of the pores with consistent use. Adding a low-potency retinoid, such as 0.1% to 0.3% topical adapalene, has shown great efficacy in reducing both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesions.5

The efficacy of retinoids is high due to blocking Toll-like receptors that recognize Cutibacterium acnes. Patients should apply the adapalene once every 2 to 4 hours every other day to build up a tolerance. Once they can tolerate it, they can then increase to nightly treatment. As patients build tolerance to the adapalene, consider advancing to prescription tretinoin (0.025%, 0.05%, and strongest at 0.1%).

This can but used in combination with one of the treatments listed in step 1.

Step 4

Systemic therapy is appropriate if a patient is not responsive to 6 consecutive months of topical combination treatment. Spironolactone is the first choice for oral therapy due to the low adverse effect profile and positive efficacy. Not only can spironolactone help with the inflammatory acne, but it can also decrease other negative processes of menopause, such as hirsutism and hair loss. Doses range from 25 mg to 200 mg a day, with 200 mg a day seen as the most effective. Spironolactone should not be used in combination with ACE inhibitors, diabetics with renal disease, or patients with a history of hyperkalemia. Continue the topical combination therapy (one of the combinations listed above) with daily spironolactone. Patients can start at 100 mg a day and slowly increase as needed based on the number of flares reported at follow-up.

Step 5

For severe, recalcitrant cases, isotretinoin can be considered with a treatment plan, starting at 0.5 mg/kg/day and taken with food. A slow taper to 1.0 mg/kg/day should be reached, with a goal of a cumulative therapeutic dose of 120 to 150 mg/kg/day.

Oral antibiotics have not been shown to provide long-term benefits but can be used for acute flares. Primary treatment includes azithromycin 500 mg 3 times a week. Classic options, such as the tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline 100 mg 2 times a day), are also effective.

Step 6

In addition to topical and systemic therapy, patients can explore a variety of cosmetic interventions to help supplement their routine for steps 1 through 4. It is not recommended that patients receive the following treatments while on isotretinoin.

Comedonal and/or persistent inflammatory acne: Comedone extraction and chemical peels can be useful. Retinol peels and chemical peels with active agents, such as salicylic acid, mandelic acid, and glycolic acid, are recommended. Peels are effective for acne lesions and scarring if they are administered properly; however, there is a risk for adverse events such as a superficial burn. This risk depends on peel ingredients, the patient’s skin type, and the provider’s experience and skill level.6

Lasers such as 585-nm and 595-nm pulsed-dye lasers, a 532 KTP laser, a 1450-nm diode laser, a 1540-nm fractional erbium-glass laser, intense pulsed light, and radiofrequency devices are all effective options if completed in a series.7

Nodulocystic acne:

In-clinic procedures such as cyst aspirations and steroid injections using 10 mg/kg intralesional triamcinolone (Kenalog) are beneficial for rapid relief and have well-tolerated adverse effects, if any. Intralesional Kenalog can cause atrophy if not diluted properly for the lesion it is being administered into. Although well tolerated, dilution and administration technique are important to achieve the desired cosmetic outcome and inflammation relief.

Hormone Replacement Therapy—Estrogen and Menopause:

As stated in the pathophysiology above, estrogen plays a major role in the dermal thickness and presentation of skin. Hormone replacement therapy helps maintain the high-density estrogen receptor presence, which improves dermal density, alleviates atrophy, decreases xerosis, and in turn, prevents a broken skin barrier. Estrogen receptors are vastly present on several cells in the body, especially dermal fibroblasts. Supplementing estrogen will increase the function of these dermal fibroblasts, which has a positive correlation on collagen production. Improving and maintaining collagen production helps stimulate keratinocyte proliferation.8 This provides a thicker, younger-functioning dermis, which leads to a more youthful appearance. It also increases elasticity and decreases transepidermal water loss. Not only does this lead to a more youthful appearance, but improving a broken skin barrier also means fewer chances of bacteria introduction into the epidermis and pilosebaceous unit, resulting in less acne.

In conclusion, there are a variety of treatment options to offer menopausal patients who are experiencing new, late-onset acne. Frequent follow-up is necessary to ensure the treatment plan is appropriate for the patient. Similar with adolescents and young adults, there may be periods of trial and error before patient satisfaction is met.

Cameron Clements, NP-C, is a certified family nurse practitioner and fellowship-trained medical dermatology clinician at Waccamaw Dermatology in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

References

- Perkins AC, Maglione J, Hillebrand GG, Miyamoto K, Kimball AB. Acne vulgaris in women: prevalence across the life span. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(2):223-230. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2722

- Vitale M, Gómez-Sánchez MJ, Vicente MH, Colombo F, Milani M. Efficacy, tolerability, and face lipidomic modification of new regimen with cleanser and corrective serum in women with acne-prone skin. Appl Sci. 2024;14(17):7799. doi:10.3390/app14177799

- Preneau S, Dreno B. Female acne – a different subtype of teenager acne? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(3):277-282. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04214.x

- Norris JF, Cunliffe WJ. A histological and immunocytochemical study of early acne lesions. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118(5):651-659. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb02566.x

- Thielitz A, Lux A, Wiede A, Kropf S, Papakonstantinou E, Gollnick H. A randomized investigator-blind parallel-group study to assess efficacy and safety of azelaic acid 15% gel vs. adapalene 0.1% gel in the treatment and maintenance treatment of female adult acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(4):789-796. doi:10.1111/jdv.12823

- Măgerușan ȘE, Hancu G, Rusu A. A comprehensive bibliographic review concerning the efficacy of organic acids for chemical peels treating acne vulgaris. Molecules. 2023;28(20):7219. doi:10.3390/molecules28207219

- Khunger N, Mehrotra K. Menopausal acne – challenges and solutions. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:555-567. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S174292

- Bravo B, Penedo L, Carvalho R, et al. Dermatological changes during menopause and HRT: what to expect? Cosmetics. 2024;11(1):9. doi:10.3390/cosmetics11010009

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.