- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Confronting Racial Disparities in Dermatologic Education

Author(s):

To further discuss the changing landscape of skin of color representation in dermatology, Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, and Shawn Kwatra, MD, review how they have seen representation change in their own experiences.

Including the accurate representation of all skin types in dermatologic education has never been more important for patient care, as the Skin of Color Society predicts that more than 50% of the US population will include those with skin of color by 2042.1

In 2020, researchers reported in Clinics in Dermatology that dermatology was the second least-diverse medical specialty (behind orthopedic surgery), which contributes to a lack of support for patients with skin of color.2 In 2021, Narla et al published a review of racial disparities in dermatology in Archives of Dermatological Research that addressed the lack of skin of color representation in education. The authors cited a review of 4146 textbook images from 4 general preclinical anatomy books commonly assigned at popular medical schools and found that only 4.5% of images represented patients with skin of color.3

Despite the previous lack of representation in educational materials, large-scale efforts have been made in recent years to positively change these statistics. The American Academy of Dermatology’s Skin of Color Curriculum includes a “definitive inpatient and outpatient curriculum for the diagnosis and effective treatment of skin of color disease and conditions for practicing dermatologists and dermatology residents.”4 The Skin of Color Society lists numerous resources on its website for physicians and students, including recommended skin of color textbooks, educational videos, a list of ethnic skin centers in the US, and mentorship opportunities.5

To further discuss the changing landscape of skin of color representation in dermatology, Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, and Shawn Kwatra, MD, review how they have seen representation change in their own experiences.

Christopher Bunick, MD, PhD, is a physician-scientist and an associate professor of dermatology at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

Shawn Kwatra, MD, is an associate professor of dermatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the director of the Johns Hopkins Itch Center in Baltimore, Maryland.

Q: When you were in medical school, were dermatologic conditions in patients with skin of color (including Black, Pacific Islander, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American individuals) accurately depicted?

Bunick: In many medical schools, dermatology exposure can be rather limited. I had about 1 week of dermatology training in my first and second years of medical school and a 1-month elective in early fourth year. To a medical student, dermatology is a foreign language, and one is just trying to master what a macule or papule is. Learning the primary lesions and a few common diseases was the emphasis, not different presentations of dermatologic conditions in patients with skin of color. Therefore, training at this stage of career to my recollection did not focus on or address skin of color directly. I honestly think I gained the most knowledge recognizing different clinical presentations in skin of color my first year or two out of residency. I have always felt the learning curve the first year as an attending is greater than all the years of medical school and residency combined. Nothing compares to learning from the patients you care for—and the thing about dermatology is you continue to learn from every patient every day.

Kwatra: In medical school, we only had a few days dedicated to dermatology. At the time, there were not as many available images of patients from diverse patient populations. Since then, there have been big efforts made by many in our field to make more diverse and inclusive skin atlases of dermatologic conditions. I gained the most knowledge at my own clinical practice as an attending in Baltimore, Maryland, which is one of the most diverse areas of the country. Through my own clinical practice, which is focused on itch, I have seen a lot of differences in how pruritic skin disorders such as prurigo nodularis and atopic dermatitis present uniquely in patients with skin of color. For example, atopic dermatitis in Black patients presents with more extensor and papular involvement. Prurigo nodularis in Black patients will often present with more fibrotic nodules.

Q: How have you seen the inclusion of patients with skin of color in educational and training materials change from your time as a student to now?

Bunick: There has been an infinite growth in materials, photographs, textbooks, and discussion around dermatologic disease in skin of color. There was only one direction to go: Up! I believe this has increased the competency of all dermatologists to recognize and help patients. We are a visual specialty first, data- and pathology-driven specialty second. Therefore, it starts with seeing over and over examples of skin problems in patients of various backgrounds. Education that enhances our initial ability to diagnose and converse with patients in a caring and intelligent manner is important for the overall patient experience.

Kwatra: Over the past several years there have been great efforts by leaders in our field to put together skin atlases from diverse patient populations. We are improving.

Q: As a professor, how do you teach students about the importance of accurate representation, specifically in patients with skin of color with psoriasis?

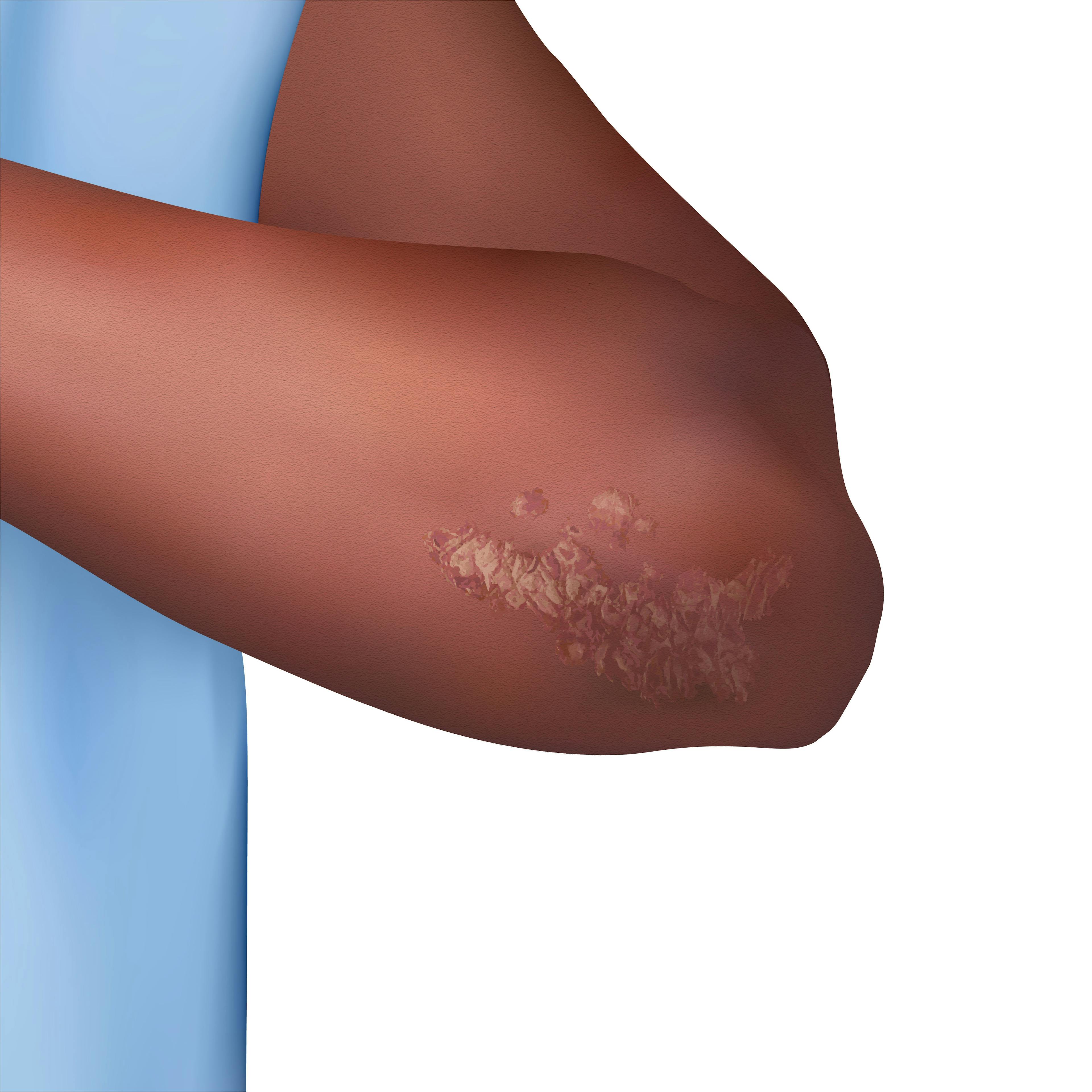

Bunick: Clinical exam is vitally important. The first impression you have of a patient is always based on pattern recognition, your memory bank or recollection of how diseases have looked in all the patients you have cared for or studied in a textbook. In sports, coaches always emphasize the fundamentals or the basics as keys to success. This is no different in dermatology; our fundamentals are morphology, distribution, symmetry, temporal relationships, modifying factors, etc. Therefore, I teach thinking about the fundamentals over and over, performing exams consistently the same way to reduce omissions or errors, and smartly utilizing laboratory and pathologic examination along with HPI to complement your physical exam. In patients with skin of color, moderate to severe psoriasis is much easier to diagnose, in my opinion, than the mild cases. Milder disease tends to mimic other skin conditions more readily, making it vital to pay attention to fundamental details.

Kwatra: I teach students that erythema or redness is less easily appreciable in patients with skin of color. So we use more objective measures, such as itch intensity, to help in assessing disease severity.

Q: Are there any resources that you rely on or recommend?

Bunick: I agree with all the recommendations and materials provided by the AAD and Skin of Color Society.

Kwatra: I often times use the worst-itch rating scale, or WI-NRS, to ask patients—on a scale of 0 as no itch to 10 as the worst imaginable itch—what is the worst itch that they have had over the preceding 24 hours as an objective measure.

Q: As a physician, what key differentiating clinical presentations of psoriasis are you looking for when diagnosing and treating patients with skin of color?

Bunick: When it comes to the appearance of psoriasis plaques, the common pink to red color seen in lighter skin tones may appear more gray or brown in skin of color. This can also affect the scale, which may appear darker as well. Resolved plaques more commonly leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation [in skin of color] than in lighter skin. But the ability of plaques to present on symmetric locations, such as elbows and knees, is the same, and that pattern recognition is important to diagnosis, as is evaluating the scalp, genitals/buttocks, and nails for clues to psoriasis. All patients with potential psoriasis should be asked about joint pains due to psoriatic arthritis. When in doubt about whether it is truly psoriasis, compared with atopic dermatitis or nummular eczema, for example, then a skin biopsy can be very helpful for diagnosis. Definitive diagnosis is important if a provider is considering a biologic or systemic therapy.

Kwatra: Patients with skin of color with psoriasis often have less obvious erythema or redness that may appear violaceous or hyperpigmented in color. Postinflammatory hypo- and hyperpigmentation are common as well.

Other key presentations I look for include the following:

- Less conspicuous erythema that may appear violaceous or hyperpigmented

- Postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation

- Potential clinical mimickers of psoriasis, such as lichen planus (especially hypertrophic type) or cutaneous lupus erythematosus (discoid and subacute)

- Potential increased area of involvement/BSA at initial presentation

- Scalp psoriasis in Black individuals, including the impact of hair texture, styling practices, and washing frequency on selection of topical therapy and severity

- Potential traditional/cultural therapies used before seeking a dermatological consultation

References

1. Skin of Color Society. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/

2. Akhiyat S, Cardwell L, Sokumbi O. Why dermatology is the second least diverse specialty in medicine: how did we get here? Clin Dermatol. 2020;38(3):310-315. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2020.02.005

3. Narla S, Heath CR, Alexis A, Silverberg JI. Racial disparities in dermatology. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315(5):1215-1223. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02507-z

4. New skin of color curriculum helps improve treatment for patients with darker skin tones. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://www.aad.org/member/education/professional-education/courses/skin-of-color-curriculum

5. Dermatology resources. Skin of Color Society. Accessed August 15, 2023. https://skinofcolorsociety.org/dermatology-resources/

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.