- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Treating All Skin Tones

Author(s):

Mona Shahriari, MD, introduces "Psoriasis Gaps in Care," a special section of the Dermatology Times September print issue dedicated to skin of color research in psoriasis.

Mona Shahriari, MD

The United States is one of the most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations in the world. While our nation continues to diversify, patients of color continue to face challenges with misdiagnosis, undertreatment, underrepresentation in clinical trials, and access to quality health care, particularly specialty care. As a dermatologist, treating patients with psoriasis—especially those from diverse backgrounds—and offering them inclusive care has always been a passion of mine.

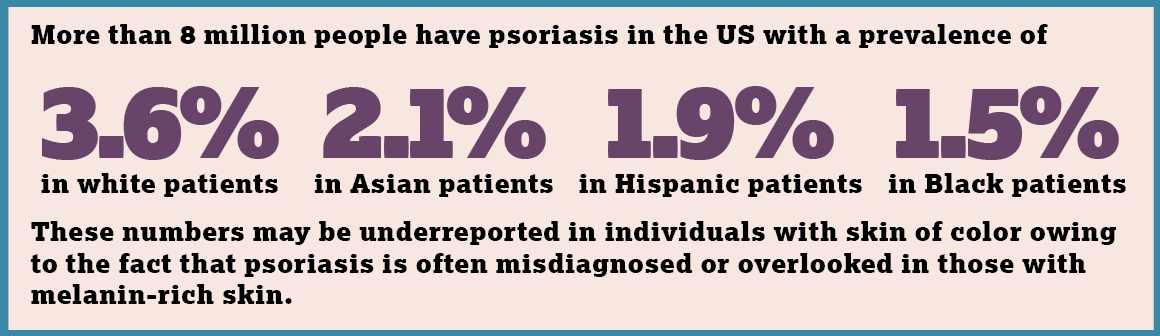

Psoriasis has a global reach, with about 125 million patients worldwide struggling with this disease. According to the National Psoriasis Foundation, more than 8 million people have psoriasis in the US with a prevalence of 3.6% in white patients, 2.1% in Asian patients, 1.9% in Hispanic patients, and 1.5% in Black patients.1 But these numbers may be underreported in individuals with skin of color owing to the fact that psoriasis is often misdiagnosed or overlooked in those with melanin-rich skin.

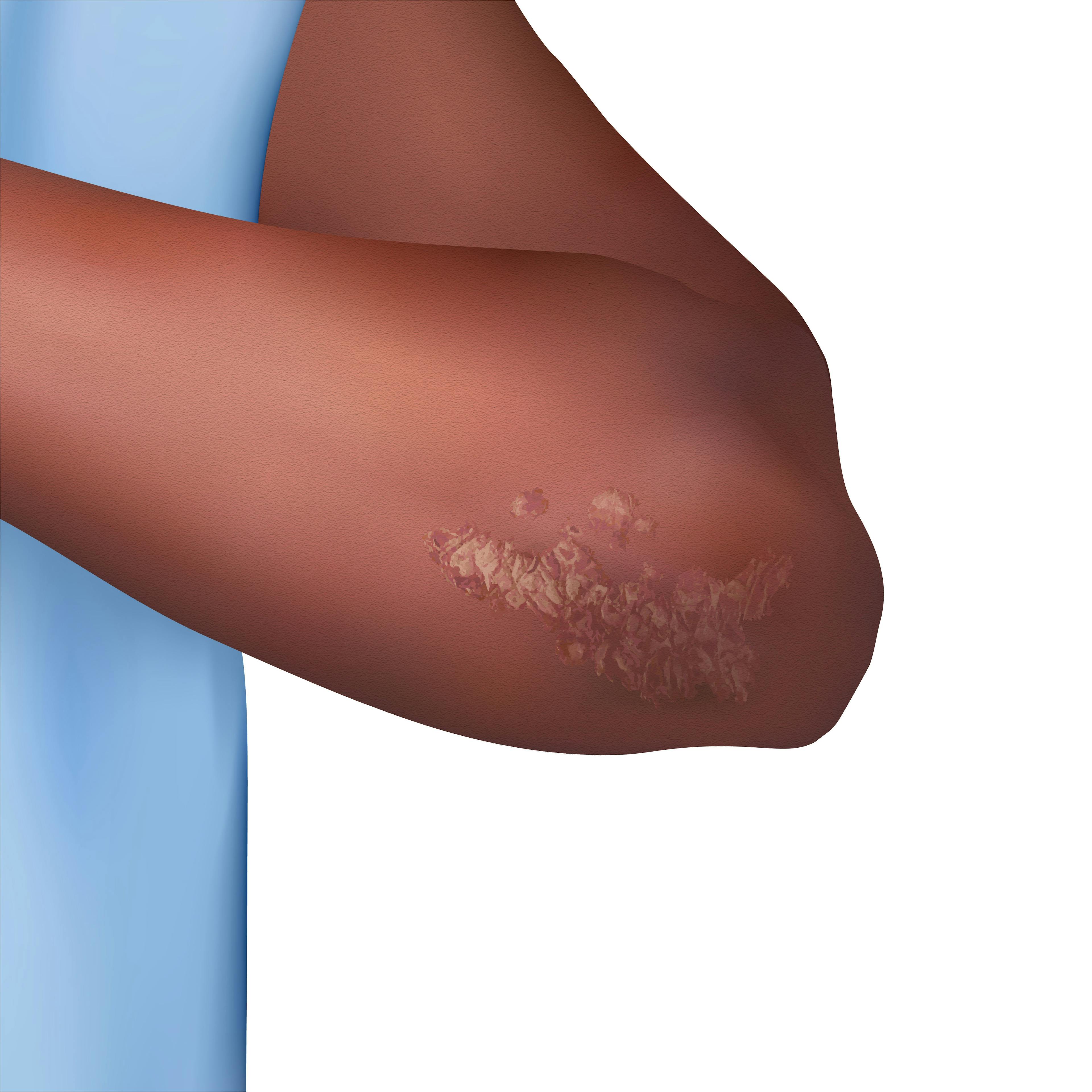

The gaps that lead to misdiagnosis and undertreatment of psoriasis in patients with diverse skin tones start at the level of medical school and residency education. Images showing skin of color are underrepresented in major textbooks as well as teaching resources, and training focusing on the nuances of treating skin disease in diverse skin tones is limited. This is compounded by the fact that skin of color is not readily seen in advertisements or public images. I challenge you to visit Google Images and search for psoriasis. You will see limited skin of color images, or none, depending on how far you scroll down. This limited training and exposure ultimately results in clinicians who are not proficient in diagnosing and treating psoriasis in patients with diverse skin tones.

For clinicians who are comfortable diagnosing psoriasis in patients with skin of color, further challenges exist. The language used to guide clinicians on assessing disease severity—in particular erythema—uses the word red a lot. Although this may work in lighter skin tones, for melanin-rich skin this language can be problematic. In darker skin tones, erythema is not always red; it can be violet, red, or even brown. For clinicians who accurately diagnose the psoriasis, their unfamiliarity with the presentation of erythema in melanin-rich skin can lead to underassessment of disease severity and undertreatment of the psoriasis. Moreover, postinflammatory pigment alteration is known to disproportionately affect our patients with skin of color and can often be more distressing than the psoriasis itself. However, these pigmentary changes are not captured in our assessments of disease severity, which may lead clinicians to dismiss or downplay their importance. Not acknowledging and treating the pigmentary changes may lead to our patients with skin of color experiencing further psychosocial burden from their psoriatic disease.

Finally, social determinants of health disproportionately affect patients with skin of color and influence health equity for these patients. Some barriers include financial stability, education, access to reliable transportation, and access to quality health care, including specialty care. All these factors can contribute to these patients’ ability to receive consistent care from a dermatologist to effectively treat and manage their psoriasis.

With the continued diversification of our nation and the representation of a spectrum of diverse skin tones in our clinics, as dermatologists, it is now more important than ever to gain comfort in treating skin disease in skin of color. We need to be aware that diagnosing and managing psoriasis in patients with skin of color comes with unique challenges. It is through education on the diagnostic and treatment nuances of this disease in melanin-rich skin, awareness of the social determinants of health that affect patients with skin of color, and cultural awareness and sensitivity toward patients from diverse ethnic backgrounds that we can enable them to receive high-quality health care in an inclusive society that recognizes them for their unique selves.

Reference

- Armstrong AW, Mehta MD, Schupp CW, Gondo GC, Bell SJ, Griffiths CEM. Psoriasis prevalence in adults in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):940-946. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.2007

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.