- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Managing Acne Vulgaris During Pregnancy and Lactation

Author(s):

During pregnancy and lactation, physiological changes occur in the body that can impact the development and management of acne.

Introduction

Pregnancy and lactation bring about significant changes in a woman’s body, including hormonal fluctuations, particularly, increased levels of androgens, which can contribute to the development or exacerbation of acne.1 Similarly, lactation is associated with hormonal changes, including elevated levels of prolactin, which can influence acne development.1

Navigating acne treatment during pregnancy and lactation requires careful consideration of the physiological changes that occur during these stages. The impact of acne on these patient populations extends beyond physical discomfort, potentially leading to significant psychological and emotional effects.

The study conducted by Ly et al aimed to provide an updated summary of existing literature on acne treatments specifically during pregnancy and lactation.1 The findings of this study and other relevant research can contribute to the development of tailored treatment plans and consensus-based guidelines to improve the care provided to these populations.

Discussion

Acne Treatment Considerations During Pregnancy and Lactation

During pregnancy and lactation, physiological changes occur in the body that can impact the development and management of acne. Hormonal fluctuations, increased sebum production, and altered immune function contribute to the prevalence and severity of acne during these periods.2 When considering acne treatment options, safety considerations become paramount. Dermatologists must carefully assess the potential risks and benefits of various treatment options to ensure the well-being of the mother and developing fetus as well as the newborn.

Topical treatments offer a noninvasive approach to acne management.2 Ingredients such as azelaic acid and benzoyl peroxide are considered safe and effective options for mild to moderate acne.1 These work locally and have minimal systemic absorption, reducing the risk of adverse effects on the fetus or nursing infant.1,2 Moreover, data show no risk from these minimally absorbed topical agents.1,2

Oral medications, on the other hand, carry a greater risk because of their systemic effects.1 Certain oral antibiotics, such as cephalexin and penicillin, are considered safe during pregnancy and lactation and may be prescribed for moderate to severe acne that fails to respond well to topical therapy treatment alone.3

Procedural interventions, including intralesional corticosteroids and light/laser therapies, offer additional options for acne management.1 Intralesional corticosteroids are effective for treating acne cysts and inflammatory nodules, with minimal systemic absorption and low risk to the fetus.1,3 Light and laser therapies, such as narrowband UV-B (NBUVB) phototherapy and photodynamic therapy (PDT), have limited evidence but show promising results without known teratogenic effects.1

The study conducted by Ly et al provides an assessment of the evidence regarding the safety and efficacy of different acne treatment options during pregnancy and lactation.1 This information can guide dermatologists in making informed decisions and developing tailored treatment plans, ensuring optimal care and minimizing potential harm to both mother and child.

Topical Treatments for Acne Vulgaris in Pregnant and Lactating Patients

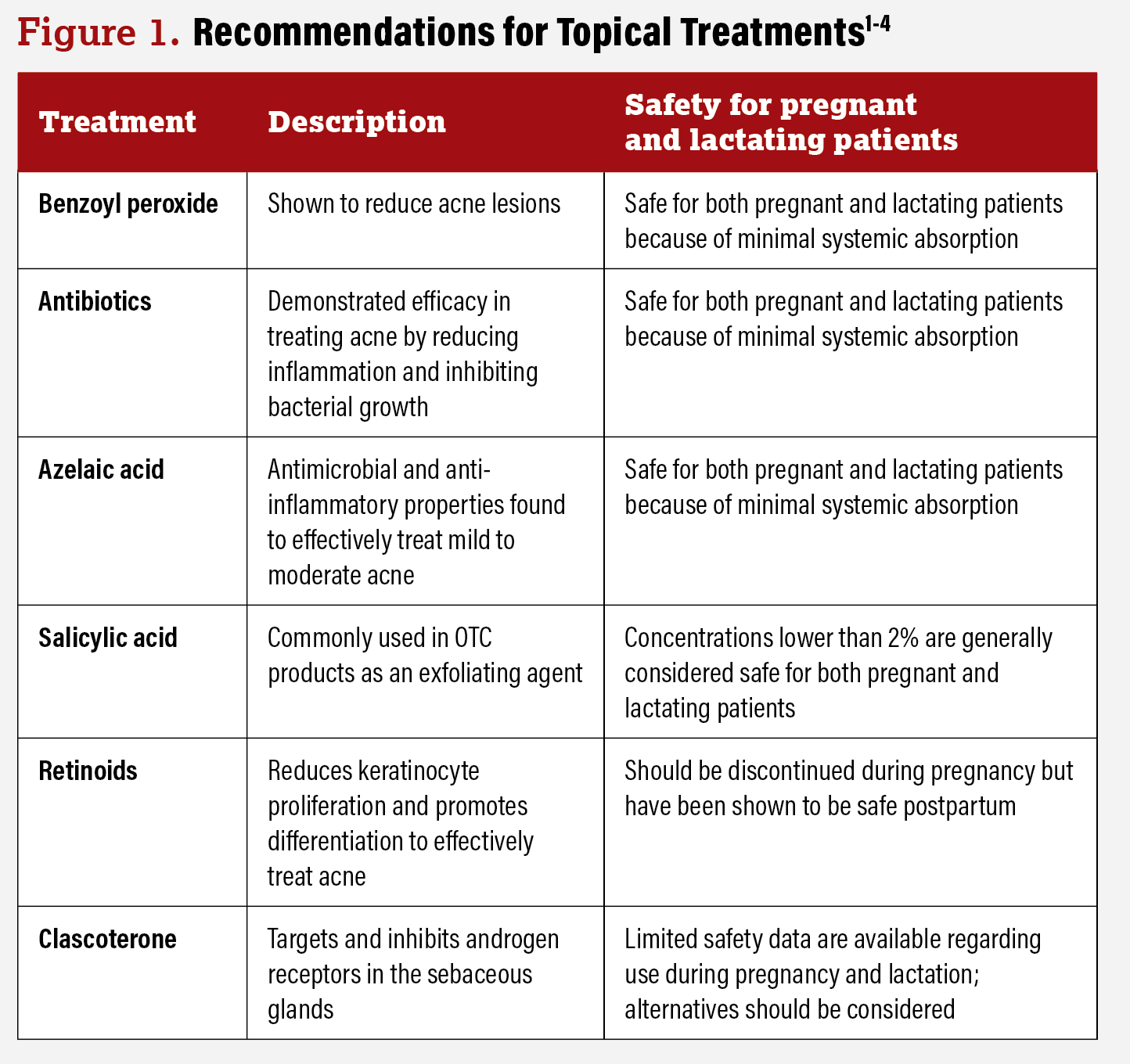

Commonly used topical agents for acne treatment during pregnancy and lactation include benzoyl peroxide, antibiotics, azelaic acid, salicylic acid, and retinoids1,3 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Benzoyl peroxide, a widely used topical treatment, has shown efficacy in reducing acne lesions.1 It is considered safe for use during pregnancy and lactation because of its minimal systemic absorption.1,3 Topical antibiotics such as clindamycin and erythromycin have demonstrated efficacy in treating acne by reducing inflammation and inhibiting bacterial growth.1 These antibiotics are generally considered safe for use during pregnancy and lactation, with low systemic absorption.1,2 Azelaic acid has antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties. It has been found to effectively treat mild to moderate acne and is considered safe during pregnancy and lactation, making it a suitable choice for individuals seeking topical treatment options.1,3 Salicylic acid, commonly used in OTC products, is an exfoliating agent. Although limited data are available on its use during pregnancy, topical use of salicylic acid in concentrations lower than 2% is generally considered safe.1 Topical retinoids such as tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene are highly effective in treating acne.1,2 However, tazarotene is known to be teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy.1,4 Topical retinoids should be discontinued during pregnancy but have been shown to be safe postpartum.1

Other topical agents, including clascoterone, have been discussed for acne management.1 Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor that has been approved for the treatment of acne vulgaris.1,2 Clascoterone works by specifically targeting and inhibiting androgen receptors in the sebaceous glands.2 Androgens, such as testosterone, play a role in the development and exacerbation of acne by stimulating the production of sebum. Limited safety data are available regarding use during pregnancy and lactation, and thus alternatives should be considered because of uncertainty of risk.1,2

Oral Medications for Acne Vulgaris in Pregnant and Lactating Patients

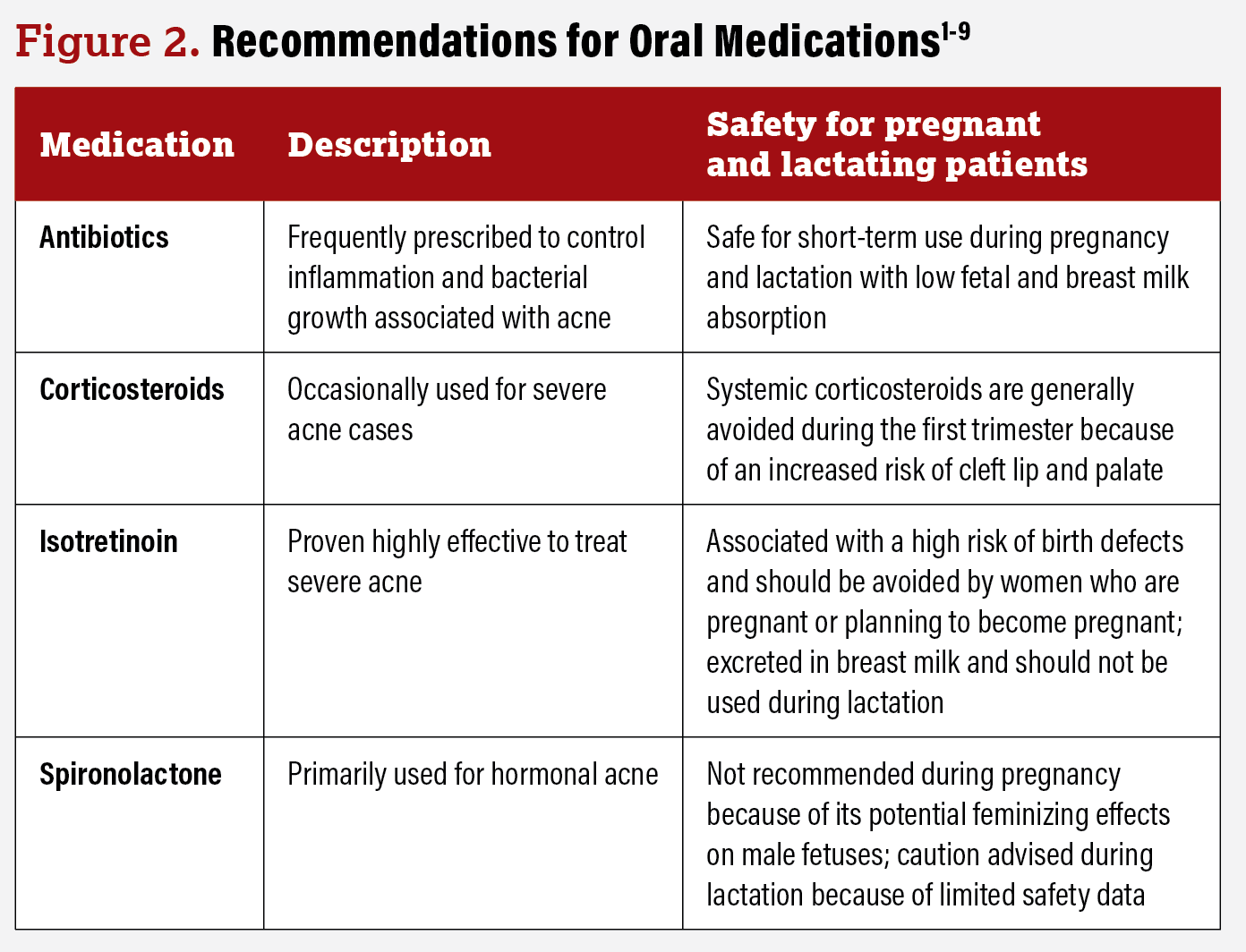

Antibiotics such as penicillin and cephalexin are frequently prescribed to control inflammation and bacterial growth associated with acne.1 These antibiotics are generally considered safe for short-term use during pregnancy and lactation, with low fetal and breast milk absorption.1,3 However, prolonged or excessive antibiotic use should be avoided.1 Corticosteroids, including low-dose prednisone, are occasionally used in severe cases of acne. However, systemic corticosteroids are generally avoided during the first trimester because of an increased risk of cleft lip and palate.1,4 Isotretinoin, a highly effective oral medication for severe acne, is known to be teratogenic and is contraindicated during pregnancy.1,5 It is associated with a high risk of birth defects and should be avoided by women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant.1,6 Additionally, isotretinoin is excreted in breast milk and should not be used during lactation.4,7 Spironolactone, a medication primarily used for hormonal acne, is not recommended during pregnancy because of its potential feminizing effects on male fetuses.1,2 It is contraindicated in pregnant individuals, and women of childbearing potential should use effective contraception while taking spironolactone.1,8 Limited data are available on its safety during lactation, and caution is advised9 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Procedural Interventions for Acne Vulgaris

Commonly discussed procedural interventions include intralesional corticosteroids as well as light and laser therapies.1 Intralesional corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone acetonide, have been found to be effective in treating acne cysts and inflammatory nodules.1 Research suggests that small amounts of intralesional corticosteroids have minimal systemic absorption, making them unlikely to increase fetal risk; therefore, they are considered safe for use during both pregnancy and lactation.1

Light and laser therapies offer alternative treatment options for refractory acne, and include NBUVB, PDT, Nd:YAG laser, and pulsed-dye laser treatments.1 These therapies have no known teratogenic effects and have been successfully used to treat acne in pregnant patients.1 However, high cumulative NBUVB doses may reduce folic acid levels, raising concerns about fetal development.1 It is recommended that folate levels be periodically checked for appropriate folic acid supplementation during these treatments.1 Topical aminolevulinic acid, often used in conjunction with PDT, is not considered safe during pregnancy.1 A newly cleared 1726-nm laser system may be an option for pregnant patients, although more safety evidence is needed.1 There are no specific studies on laser and light therapies in lactating patients; however, minimal systemic absorption suggests low concern.1

Patient Counseling and Management Strategies

Patient education and counseling are crucial aspects of managing acne during pregnancy and lactation. Strategies for managing acne in these populations should emphasize safe and effective approaches that are supported by evidence-based practices. Acne during pregnancy and lactation can also have a significant psychosocial impact.1,10 By prioritizing patient education and support, implementing effective strategies for acne management, and addressing the potential psychological impacts, dermatologists can empower patients to make informed decisions about their acne treatment.

Looking Forward

These findings emphasize the importance of individualized treatment selection based on acne severity, trimester-specific risks, and maternal and fetal medical history. The study by Ly et al recommends first-line topical treatments such as benzoyl peroxide and azelaic acid for mild to moderate acne during any phase of pregnancy or lactation.1 In terms of oral medications, certain antibiotics can be considered but with careful consideration of trimester-specific safety.5 Isotretinoin, a potent oral medication, should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation because of its known teratogenic effects.1-3,11 Procedural interventions, such as intralesional corticosteroids and light and laser therapies, show promise but require further research to establish their safety and efficacy profiles in these patient populations.1

Managing acne during pregnancy and lactation requires careful safety considerations for both the mother and baby. By understanding the available evidence and adopting a comprehensive approach, dermatologists can provide effective treatment options and support to individuals experiencing acne during these critical periods. Continued research should focus on establishing consensus-based guidelines for acne management while optimizing treatment plans to ensure the safety and well-being of pregnant and lactating patients seeking acne treatment.

Isabella Tan is from Potomac, Maryland, and is a rising second-year medical student at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Bernard Cohen, MD, is a professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- Ly S, Kamal K, Manjaly P, Barbieri JS, Mostaghimi A. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation: a narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13(1):115-130. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00854-3

- Kong YL, Tey HL. Treatment of acne vulgaris during pregnancy and lactation. Drugs. 2013;73(8):779-787. doi:10.1007/s40265-013-0060-0

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part I. Pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):401.e1-415. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.010

- Butler DC, Heller MM, Murase JE. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part II. Lactation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(3):417.e1-427. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.009

- Pugashetti R, Shinkai K. Treatment of acne vulgaris in pregnant patients. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26(4):302-311. doi:10.1111/dth.12077

- Chien AL, Qi J, Rainer B, Sachs DL, Helfrich YR. Treatment of acne in pregnancy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(2):254-262. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.02.150165

- Meredith FM, Ormerod AD. The management of acne vulgaris in pregnancy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14(5):351-358. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0041-9

- Tyler KH, Zirwas MJ. Pregnancy and dermatologic therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4):663-671. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.09.034

- Awan SZ, Lu J. Management of severe acne during pregnancy: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2017;3(3):145-150. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.06.001

- Leachman SA, Reed BR. The use of dermatologic drugs in pregnancy and lactation. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24(2):167-vi. doi:10.1016/j.det.2006.01.001

- Reed BR. Dermatologic drugs, pregnancy, and lactation. A conservative guide. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133(7):894-898

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.