- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

New treatments help improve rosacea management

Author(s):

Recent data sheds light on the pathogenesis of rosacea and outlines treatment options to better manage patients.

As the pathogenesis of rosacea is still largely unclear, physicians often grapple with finding an optimal treatment and management plan. However, continued research has highlighted neuroinflammation and neurogenic inflammation as important contributing factors in the development of the skin condition, and insights like these have led to improvements in therapeutic management.

RELATED: Skin microbiota linked with systemic disease, rosacea

Rosacea occurs in approximately 10% of individuals usually after the fourth decade of life and is diagnosed in over 13 million patients in the United States alone. The condition often carries implications far beyond the skin and can take a significant toll on a patient’s psyche and general well-being.

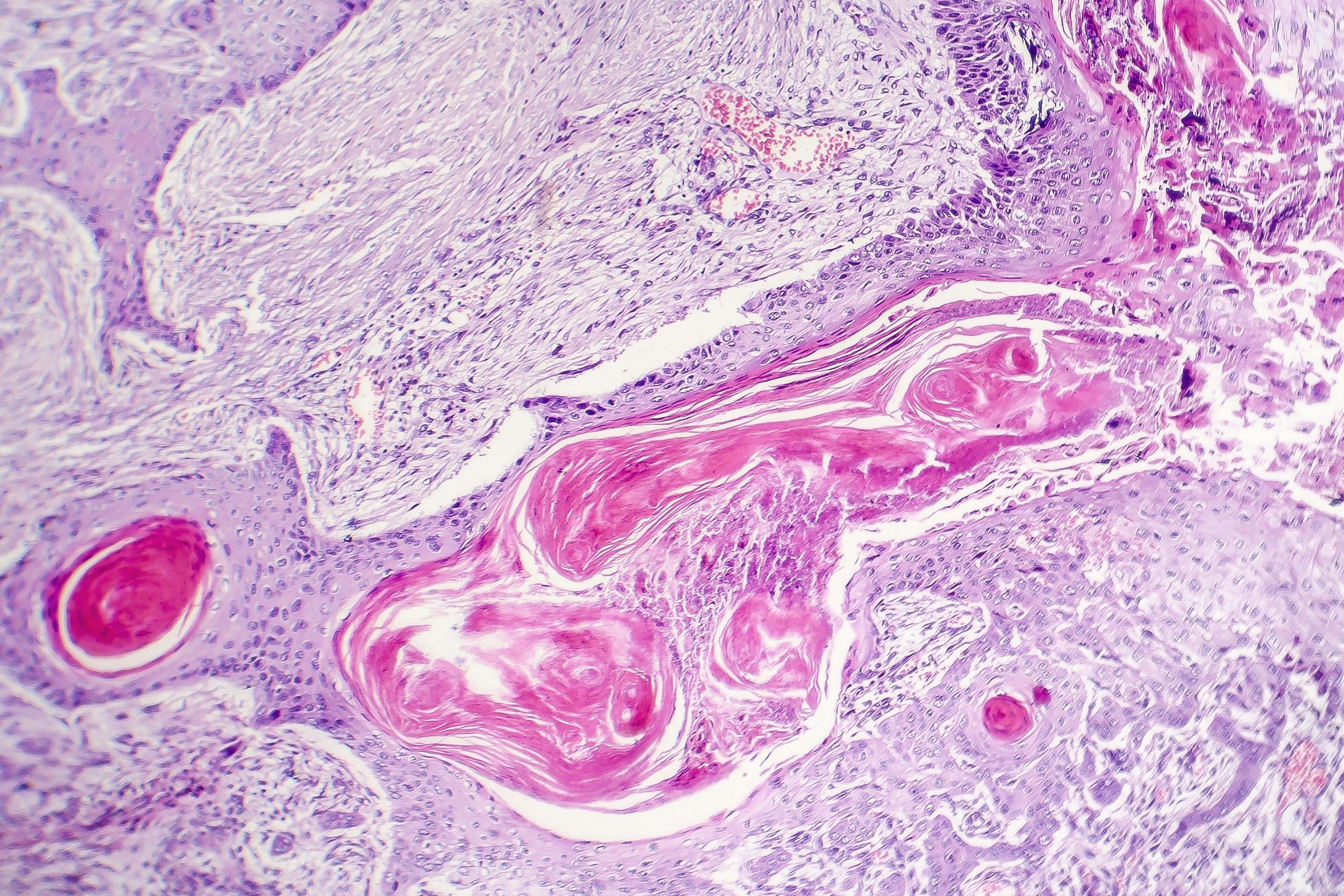

The condition is characterized by a mosaic of symptoms, including facial erythema and telangiectasias, papules and pustules, as well as facial edema, typically occurring on the central face around the nose, cheeks, forehead and chin. According to the presentation of symptoms, it can be further divided into four subtypes including erythematotelangiectatic rosacea (erythema, flushing, telangiectasias), papulopustular rosacea (erythema, edema, acne-like lesions), phymatous rosacea (rhinophymatous changes), and ocular rosacea, which can cause significant inflammation leading to dryness, redness and irritation of the eyes, resulting in transient vision changes and even permanent vision damage after persistent chronic inflammation of the cornea.

“The current pathophysiological model of rosacea implicates an upregulated, dysregulated innate immune system prone to excessive inflammation and vasodilation coupled with neurogenic dysregulation and extrinsic triggers and exacerbating factors,” writes Justin W. Marson, M.D., department of medicine, University of California at Irvine, Orange, Calif., and colleagues, in the study recently published in the International Journal of Dermatology.1

Hyperactive neurovasculature appears to be one of the keys in developing symptoms of rosacea. According to the study authors, vasodilation and lymphatic dilation have been implicated in the flushing (physiologic acute neurogenic inflammation) and blushing (sympathetic driven transient pinkness of the central face and cheeks from emotion and stress) often seen in rosacea patients. These symptoms can be stimulated and exacerbated by spices, hot and cold temperatures, exercising and alcohol.

Dysregulated innate and adaptive immunity also play a central role in developing rosacea symptoms, which can often be seen clinically as papules and pustules. It is thought that the subtypes of rosacea may actually represent a spectrum of inflammation and immune system dysregulation.

RELATED: FDA approves first topical minocycline for rosacea

The microbiome has also been thought to instigate and propagate a dysfunctional immune system and, of the several suspected cutaneous microbes, demodex folliculorum (and its native microbe Bacillus oleronius) has most notably been implicated in the inflammatory response in rosacea. Past studies2,3 have shown Demodex density to be higher in areas of rosacea compared with healthy skin in the same patient, and almost six times higher in patients with rosacea compared with healthy subjects.

The conventional wisdom for rosacea is that the innate immune system cannot appropriately recognize the commensal organisms that live and breed naturally on the skin such as C. acnes, S. epidermidis, and, perhaps, Demodex. The result is an inflammatory response to these organisms by the innate immune system, translating clinically into rosacea. Moreover, the authors state that patients with rosacea may have an altered gastrointestinal microbiome that can contribute to their disease symptoms, which can be associated with gastrointestinal disorders, including celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel syndrome, as well as other systemic inflammatory diseases.

“In designing a therapeutic approach, it is also important for physicians to not only determine severity but also ask the patient of their perception of disease severity and what about the disease process concerns them the most. These two principles, in turn, can help guide development of the therapeutic regimen,” the authors write.

Appropriate skin hygiene as well as lifestyle modifications that include avoiding the potential precipitating and exacerbating factors of rosacea can help mitigate disease severity. According to the authors, patients should be encouraged to avoid chemical or physical exfoliants and alcohol-based topical products, use moisturizers, wash their face with mild, synthetic detergent-based products, as well as apply sunscreens with an SPF 30 or greater that can provide broad-spectrum UV and visible light protection.

A number of topical preparations can be used to help address the persistent erythema, telangiectasias and flushing including brimonidine 0.33% gel, an alpha-2 adrenergic agonist, and oxymetazoline 1% cream, an alpha-1 adrenergic agonist, both aimed at constricting facial blood vessels. Laser and light therapies including the pulsed dye (PDL) and potassium-titanyl-phosphate (KTP) lasers as well as intense-pulsed light (IPL) have also demonstrated efficacy in diminishing erythema and some degree of flushing, removing telangiectasias and improving quality of life.

RELATED: LEO Pharma’s azelaic acid foam for rosacea now available

A range of first-line topical and oral agents are currently being used to treat the papules and pustules in rosacea including topical ivermectin 1% cream, azelaic acid 15%, and metronidazole 0.75% gel, cream or lotion. Other agents that have also proven effective include clindamycin 1% gel with and without 5% benzoyl peroxide, erythromycin, minocycline, permethrin and topical retinoids. In more severe cases, varying combinations of topical and oral medications are also employed.

Isotretinoin as well as the systemic antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory agents used for papulopustular rosacea can also work well in the early active inflammatory stages of phymatous rosacea, while advanced disease hallmarked by hypertrophy and nodular growths may be best addressed with procedural techniques including ablative CO2 or erbium laser, radiofrequency or surgical debulking.

According to the authors, ocular rosacea can occur in approximately half of patients with cutaneous rosacea, may precede cutaneous symptoms in 20% of patients, or can develop independently. Here, first-line treatments include topical azithromycin and calcineurin inhibitors used alone or in combination, while more severe ocular symptoms can be treated with oral azithromycin, anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline, as well as other tetracyclines.

“Most patients with rosacea present with combination disease of papules, telangiectasias, erythema and pustules. Successful treatment of rosacea patients requires ascertaining what aspects of their disease are most troublesome to them and devising a multi-therapy approach to address all clinical findings,” the authors write.

Disclosure:

Dr. Marson reports no relevant disclosures.

References:

1. Marson JW, Baldwin HE. Rosacea: a wholistic review and update from pathogenesis to diagnosis and therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Dec 27. doi: 10.1111/ijd. 14758. Epub 2019 Dec 27. Review.

2. Forton F, Germaux MA, Brasseur T, et al. Demodicosis and rosacea: epidemiology and significance in daily dermatologic practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005; 52: 74–87.

3. Casas C, Paul C, Lahfa M, et al. Quantification of Demodex folliculorum by PCR in rosacea and its relationship to skin innate immune activation. Exp Dermatol. 2012; 21: 906–910.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.