- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

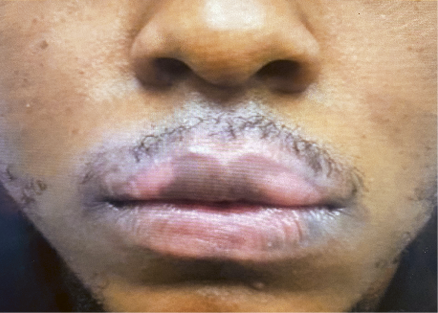

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

News

Article

Dermatology Times

Launching Into Space: Is Dermatology Ready?

Author(s):

Star Trek may call space “the final frontier,” but it’s really the next exciting frontier for humans. For now, we can learn about the various new innovations and therapies for skin disease at the AAD annual meeting—and continue to strive to improve our patients’ lives here on Earth.

3, 2, 1 … blast off! The 2024 American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting is right around the corner, and it promises to boldly go where no dermatologist has gone before: outer space.

Why space? William Shatner, who famously played Captain James T. Kirk in the original "Star Trek" series, is the keynote speaker at the plenary session. Current AAD president, Terrence A. Cronin Jr, MD, will lead a discussion with Shatner about his long and exciting career, spanning not only acting but also writing and other enterprises.

I am excited about this talk, as I fondly remember watching Star Trek with my father as a young boy and being fascinated by the science and space exploration. What is your favorite "Star Trek" movie? Mine is "Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home" because of its witty humor and evaluation of the human ego when it comes to alien interaction with Earth. (Spoiler alert: The space probe wanted to hear the sounds of humpback whales, not humans!)

Unfortunately, none of the annual meeting sessions will discuss caring for skin or treating skin disease when in space, but there has been some research on the topic—and maybe even signs of a growing need to be ready for it. Although it seems like science fiction, the reality is that entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are accelerating innovation for space travel with their private companies SpaceX and Blue Origin, respectively. Were you glued to the television when SpaceX sent their Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station for the first time? I know I was mesmerized by the touch screen technology. Talks about colonizing the moon and traveling to Mars is slowly transforming into reality by SpaceX, Blue Origin, NASA, and others. This begs the question: Is dermatology prepared to care for its space patients?

Over the past several decades, astronauts have bravely paved the way in providing clues as to what happens to human skin in space. As a result, there is a growing body of literature on the impact of space exploration on our skin. For instance, in “Dermatologic Manifestations in Spaceflight: A Review,” Carly Dunn, McKenna Boyd, and Ida Orengo, MD, eloquently discussed the reaction of skin to the microgravity and higher cosmic radiation environment of space.1 They found that the most common medical problem in space is skin related. In addition, studies have estimated 1.12 skin rashes per flight year, which is approximately 25-fold higher than the rate per year on Earth.2 The increased prevalence has been partially attributed to the cold, dry, low-humidity environment of space (or, more appropriately, spaceships). These conditions exacerbate xerosis of the skin and can cause atopic dermatitis flares.

Irritant contact dermatitis is often an issue because of the chemicals used on spacecrafts and in space stations, as is documented in a case of irritant contact dermatitis related to a biosensor electrolyte paste.3 Therefore, it isn’t a stretch to believe dermatologists will be needed on the moon, Mars, and any place we travel in the universe.

Spaceflight itself has been associated with skin issues, with 3 general skin changes observed: (1) up to 143% increase in dermal collagen after 6 months,4-5 accompanied by loss of elasticity; (2) epidermal thinning to 30 µm, thought to be due to increased epidermal turnover time6; and (3) microbiota changes.1 In the case of the latter, microbiome studies have conflicting data, so additional examination with modern technologies is needed to understand how microgravity impacts the skin microbial ecology when in space. Interestingly, the collagen, elasticity, and epidermal thinning all corrected upon return to Earth. In addition to skin atrophy, deregulation of the hair follicle cycle was observed in mice who spent 3 months in space.7 The question remains: What happens to skin if humans permanently live in space?

Given the prominent role of the immune system in many dermatologic conditions, it is interesting that some astronauts have experienced immune dysregulation during their time in microgravity. The immune dysregulation may be brought on by stressors, both physical and psychological, as evidenced by elevated cortisol and catecholamine (known as stress hormones) levels in astronaut urine.1,8 The increased stress also plays a role in increased infections in space, particularly the reactivation of herpes virus. Studies on cytokine changes among astronauts have identified a Th1 to Th2 cytokine shift among astronauts regardless of their duration in space. The heightened Th2 response (IL-4 increased up to 21-fold) has been linked to latent virus reactivation,9 and elevations in both IL-4 and IL-13 could explain the increased risk for atopic dermatitis flares among humans in space.

Beyond the skin, Afshin Beheshti, PhD, bioinformatician and principal investigator at Blue Marble Space Institute of Science/NASA Ames Research Center, and other space experts published a phenomenal review of the biological features of spaceflight. This review highlighted 6 basic molecular and cellular characteristics: elevated oxidative stress, DNA damage from ionizing radiation, increased mitochondrial dysfunction, epigenetic and gene regulation changes, telomere changes, and alterations in the host-microbiome interactions.10 What might happen during a long-term excursion to Mars? Modern medicine must address challenges such as cardiovascular dysregulation, central nervous system impairment, cancer, muscle degeneration, osteoporosis, immune dysfunction, liver impairment, and circadian rhythm disruption to create a sustained living opportunity for humans beyond Earth.10

Don’t let these health concerns scare you from a trip to space. They certainly didn’t prevent Shatner from traveling into space via Blue Origin—and they didn’t seem to scare off Travis Kelce, Kansas City Chiefs football player, who recently revealed that SpaceX reached out to him about a trip to space.

Star Trek may call space “the final frontier,” but it’s really the next exciting frontier for humans. For now, we can learn about the various new innovations and therapeutic approaches to skin disease at the annual meeting and take pride in how we are constantly striving to improve our patients’ lives here on Earth.

For instance, the aforementioned plenary session will also feature 4 award lectureships: Henry W. Lim, MD, will present the Clarence S. Livingood, MD, Award and Lectureship; Patricia A. Treadwell, MD, will present the John Kenney Jr, MD, Lifetime Achievement Award and Lectureship; Brian S. Kim, MD, will present the Marion B. Sulzberger, MD, Research Award and Lectureship; and Brian J. Druker, MD, will present the Lila and Murray Gruber Memorial Cancer Research Award and Lectureship. This plenary session certainly reaches for the stars, and I’m considering it a can’t-miss part of the program. I’m also looking forward to the many sessions and informal experiences and networking that provide us with opportunities to learn and embrace all things skin—and you can count on Dermatology Times to cover it all!

With that in mind, I invite you to visit Dermatology Times at booth 3532, where you can share with us not only what you’re learning but also which one of us dermatologists should be the first in space!

To paraphrase Spock, “Welcome, William Shatner, to the exciting, rewarding, and challenging field of dermatology. And may all in dermatology live long and prosper.”

References

1. Dunn C, Boyd M, Orengo I. Dermatologic manifestations in spaceflight: a review. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(11):13030/qt9dw087tt.

2. Crucian B, Babiak-Vazquez A, Johnston S Pierson DL, Ott CM, Sams C. Incidence of clinical symptoms during long-duration orbital spaceflight. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:383-391. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S114188

3. Burgdorf WH, Hoenig LJ. Dermatology and the American experience in space. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(8):877. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2557

4. Arora S. Aerospace dermatology. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62(1):79-84. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.198051

5. Seitzer U, Bodo M, Müller PK, Açil Y, Bätge B. Microgravity and hypergravity effects on collagen biosynthesis of human dermal fibroblasts. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;282(3):513-517. doi:10.1007/BF00318883

6. Tronnier H, Wiebusch M, Heinrich U. Change in skin physiological parameters in space—report on and results of the first study on man. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2008;21(5):283-292. doi:10.1159/000148045

7. Neutelings T, Nusgens BV, Liu Y, et al. Skin physiology in microgravity: a 3-month stay aboard ISS induces dermal atrophy and affects cutaneous muscle and hair follicles cycling in mice. NPJ Microgravity. 2015;1:15002. doi:10.1038/npjmgrav.2015.2.

8. Mehta SK, Laudenslager ML, Stowe RP, et al. Latent virus reactivation in astronauts on the international space station. NPJ Microgravity. 2017;3:11. doi:10.1038/s41526-017-0015-y

9. Mehta SK, Laudenslager ML, Stowe RP, Crucian BE, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Multiple latent viruses reactivate in astronauts during space shuttle missions. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;41:210-217. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2014.05.014

10. Afshinnekoo E, Scott RT, MacKay MJ, et al. Fundamental biological features of spaceflight: advancing the field to enable deep-space exploration. Cell. 2020;183(5):1162-1184. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.050

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.