- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

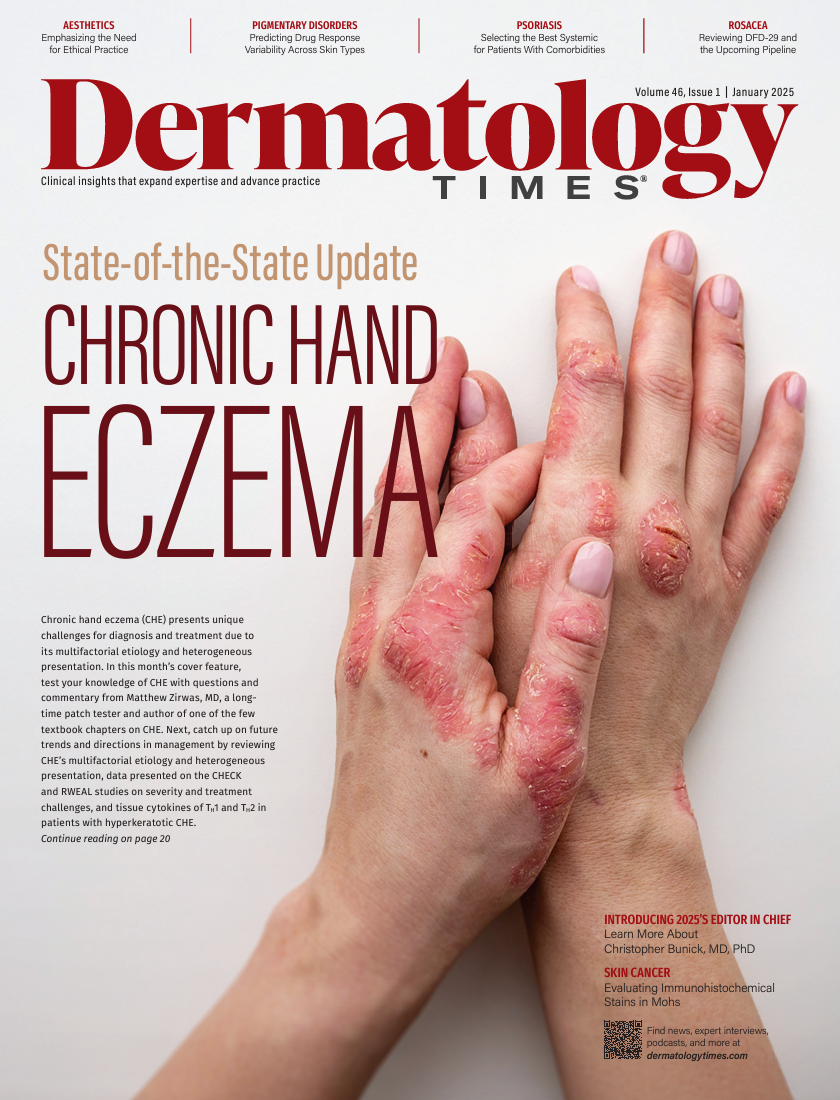

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

News

Article

Dermatology Times

Thinking Outside the Psoriatic Box: Practical Points for Systemic Success

Author(s):

Key Takeaways

- Psoriasis is associated with comorbidities like obesity and depression, necessitating a systemic treatment approach.

- Weight reduction improves biologic response in psoriasis, with GLP-1 agonists and IL-23 inhibitors as potential treatments for obese patients.

Explore systemic psoriasis management, covering obesity, depression, biologics, and innovative treatment approaches.

Psoriasis is a systemic disease; however, we as clinicians often look at it from a cutaneous perspective. Currently we are aware it is associated with metabolic syndrome, heart disease, depression, inflammatory bowel disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, arthritis, and more. Unfortunately, the current health care climate makes it difficult to coordinate care, manage and take ownership of other medical problems, and verify follow-up. However, we can use our medications in certain scenarios to tackle many of the associated comorbidities. This review highlights 2 common but overlooked comorbidities: obesity and depression.

Image Credit: © Nikkikii; ShunTerra - stock.adobe.com

Obesity

As of now, many of the FDA-approved treatments for psoriasis are not weight based with regard to dosing. The question arises: “Does weight reduction have any effect on biologic response?” The answer: yes. One study randomly assigned patients on biologics (infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, or ustekinumab) to either a normal diet or a low-calorie diet (≤ 1000 calories) and followed these patients for 24 weeks. The mean improvement in PASI score was 84% in the low-calorie diet group and 59.3% in the control group.1 Not everyone is equipped to go over dietary modifications (taking into account other comorbidities) in clinic; however, we can with appropriate guidance and also consider prescribing glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 agonists.

GLP-1 agonists are currently approved for the management of diabetes and obesity. One study evaluated GLP-1 therapy in patients with psoriasis and type 2 diabetes. While the study was small (n = 13 in the intervention group), investigators found after 12 weeks of intervention that the mean PASI of the control group decreased from a mean of 13.57 (SD, 5.49) to a mean of 7.42 (SD, 3.91) compared with the mean PASI of the treatment group, which decreased from a mean of 14.02 (SD, 10.67) to a mean of 2.40 (SD, 2.71). In addition, tissue expression of IL-17 and IL-23, not tumor necrosis factor-α, was significantly lower in the treatment group.2 While most dermatologists may not know how to prescribe GLP-1 agonists, I encourage you to learn because Eli Lilly, the maker of ixekizumab, is now allowing dermatologists to prescribe tirzepatide to patients who are obese and on ixekizumab through a special program. If you do not feel comfortable, you can find your patients an endocrinologist or primary care doctor who can prescribe it.

For those who don’t want to dabble in a new class of medications and feel uncomfortable managing potential complications, IL-23 inhibitors may be the best option for patients with obesity or overweight. In the phase 3 ECLIPSE study (NCT03090100), the proportion of patients achieving PASI 90 or PASI 100 responses at week 48 by baseline body weight (from < 60 kg to > 110 kg) was numerically higher for guselkumab-treated vs secukinumab-treated patients, particularly in the patients weighing over 100 kg.3 Similarly, risankizumab demonstrated consistent efficacy across all weight deciles compared with ustekinumab in one study.4 How does this help us? With the plethora of options, you may want to grab an IL-23 blocker when initiating a biologic in a patient with psoriasis and obesity or overweight.

Depression

Psychiatric diseases such as depression and anxiety are very common among patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. Did you know IL-17 may play a role in depression and psychiatric disorders? First let me address the elephant in the room: brodalumab. Brodalumab is an excellent biologic that blocks the IL-17 subunit A receptor. It has a black box warning for suicidality, which has been largely debunked, but let’s take a look in more detail. Blockade of this receptor leads to a 4-fold increase in circulating IL-17.5 IL-17 levels do usually normalize after 30 days after a dose. Three of the 4 patients who committed suicide did so within 30 days of receiving the dose. This does not prove causation; however, it does bring up an interesting point. Results of multiple studies have identified elevated levels of IL-17 and IL-17 mRNA expression in patients with depression. There are also some that did not show a relationship between IL-17 and depression.5

Results of a case-control study identified elevated IL-17 levels in patients with a first-episode depressive disorder, and these levels decreased with treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. In fact, results also showed the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression correlated with IL-17.6 Results of another study, albeit smaller with no control arm, did not find a significant difference in IL-23 and IL-17 levels before and after 6 weeks of antidepressant therapy in patients with major depressive disorder.7 While these data are inconsistent, there seems to be some association between IL-17 and neuroinflammation, with various models showing it can cross and disrupt the blood-brain barrier.5

How do we use this information clinically? First, screen patients with psoriasis for depression with Patient Health Questionaire-2, and if there are concerns for depression, identify suicidality (as with isotretinoin). If there are concerning signs for depression with suicidality and you are in search of a biologic, you may want to consider an IL-17A blocker such as ixekizumab, bimekizumab, or secukinumab. Do not forget to refer all potential suicide risks to the emergency department. I recently discussed a case with a local psychiatrist who admitted a patient for a suicidal attempt soon after starting bimekizumab for psoriasis, which partially inspired me to discuss this topic.

If depression is a concern without suicidality, you can consider brodalumab as well. This does not replace appropriate referral to primary care and/or psychiatry for further management of psychiatric symptoms. Be mindful that some psychiatric medications can exacerbate psoriasis. A recent case series identified success of 3 patients treated with secukinumab with underlying psychiatric diseases including depression, bipolar disorder, and anxiety.8 Interestingly, a population-based cohort study out of Taiwan followed patients with major depressive disorder for 5 years and compared those who received antidepressants with those who did not, and results showed a protective effect of antidepressant use on psoriasis development.9 While not conclusive, the results do highlight the importance of making sure patients receive care for their psychiatric illnesses.

While we cannot do it all, all the time, we do often have the ability to tailor our regimens based on each patient’s underlying medical problems. We have to remind ourselves that psoriasis is a systemic disease, and we have many therapies we can utilize to our advantage in specific scenarios.

Karan Lal, DO, MS, FAAD, is the first and only dual fellowship-trained pediatric and cosmetic dermatologist in the US practicing at Affiliated Dermatology in Scottsdale, Arizona, and a Dermatology Times editorial advisory board member.

References

- Al-Mutairi N, Nour T. The effect of weight reduction on treatment outcomes in obese patients with psoriasis on biologic therapy: a randomized controlled prospective trial. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14(6):749-756. doi:10.1517/14712598.2014.900541

- Lin L, Xu X, Yu Y, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide therapy for psoriasis patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized-controlled trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(3):1428-1434. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1826392

- Blauvelt A, Armstrong AW, Langley RG, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab versus secukinumab in subpopulations of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: results from the ECLIPSE study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(4):2317-2324. doi:10.1080/09546634.2021.19595044.

- Leonardi C, Gordon K, Longcore M, Gu Y, Puig L. Weight-based analysis of psoriasis area and severity index improvement at 52 weeks of risankizumab or ustekinumab treatment: an integrated analysis of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Presented at: 24th World Congress of Dermatology; June 10-15, 2019; Milan, Italy.

- Schiweck C, Aichholzer M, Reif A, Thanarajah SA. Targeting IL-17A signaling in suicidality, promise or the long arm of coincidence? evidence in psychiatric populations revisited. J Affect Disord Rep. 2023;11:100454. doi:10.1016/j.jadr.2022.100454

- Mao L, Ren X, Wang X, Tian F. Associations between autoimmunity and depression: serum IL-6 and IL-17 on the HAMD scores in patients with first-episode depressive disorder. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:6724881. doi:10.1155/2022/6724881

- Kim JW, Kim YK, Hwang JA, et al. Plasma levels of IL-23 and IL-17 before and after antidepressant treatment in patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(3):294-299. doi:10.4306/pi.2013.10.3.294

- Esposito M, Giunta A, Del Duca E, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of secukinumab in patients with psoriasis and major psychiatric disorders: a case series. Postgrad Med. 2020;132(2):172-175. doi:10.1080/00325481.2020.1712153

- Tzeng YM, Li IH, Kao HH, et al. Protective effects of anti-depressants against the subsequent development of psoriasis in patients with major depressive disorder: a cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:590-596. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.110

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.