- Acne

- Actinic Keratosis

- Aesthetics

- Alopecia

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Buy-and-Bill

- COVID-19

- Case-Based Roundtable

- Chronic Hand Eczema

- Drug Watch

- Eczema

- General Dermatology

- Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- Melasma

- NP and PA

- Pediatric Dermatology

- Pigmentary Disorders

- Practice Management

- Precision Medicine and Biologics

- Prurigo Nodularis

- Psoriasis

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Rare Disease

- Rosacea

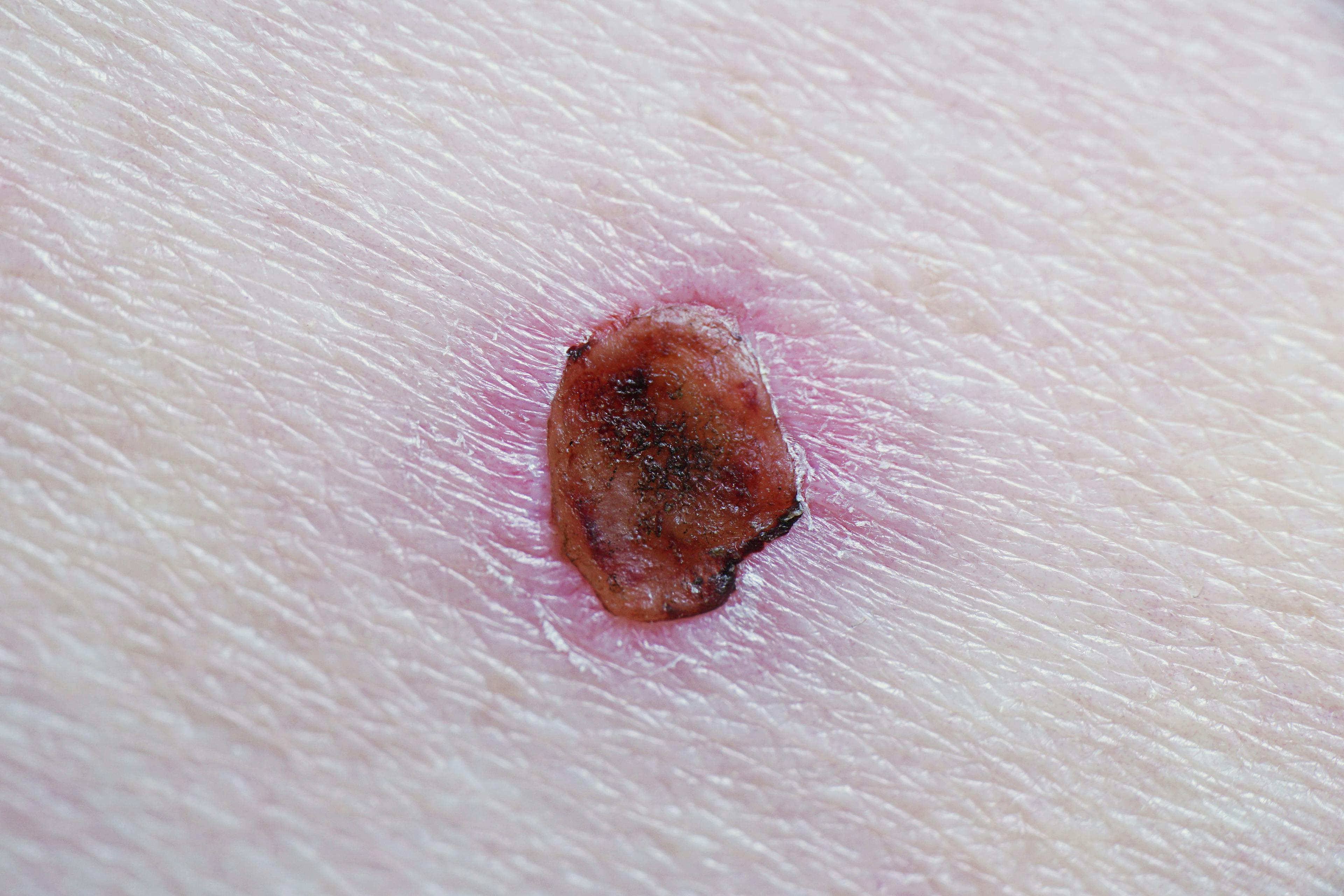

- Skin Cancer

- Vitiligo

- Wound Care

Publication

Article

Dermatology Times

Legal Issues Due To My Physician Extenders

Author(s):

In this month's Legal Eagle column, a case involving physician extenders is discussed.

DR M HAS PRACTICED dermatology for 25 years. During that time, he has hired and fired secretaries and licensed medical assistants. He has never hired licensed physician assistants and nurses. His 3 most devoted and loyal employees have worked with him for more than 2 decades.

All 3 began their work with Dr M during high school as part-time secretaries paid minimum wage. After completing high school, they became full-time employees, and their tasks included answering the phone and scheduling patient appointments. These employees loved their jobs and never sought further schooling of any kind.

Over the course of 20 years, these employees became familiar with every aspect of Dr M’s dermatology practice. Due to so much clinical staff turnover, Dr M began asking these 3 women to play the role of medical assistants. At first they took dermatologic histories from patients, but after so many years of working in Dr M’s practice, all 3 “medical technicians” became very facile at acne surgery, small biopsies, simple suturing, and even some cosmetic procedures.

Dr M is convinced that these trained workers are more reliable and perform better quality work than any licensed medical personnel ever previously employed in his office. He is quick to tell his peers about the quality of their work and the fact that no medical malpractice litigation has ever ensued because of their labors.

Unfortunately, all 3 employees are served legal papers for practicing medicine without a license. In addition, Dr M is accused of aiding and abetting the practice of medicine without a license. Such a crime is a felony in his state and could force Dr M to lose his medical license.

Dr M is incensed and seeks legal advice. He doesn’t see how his actions could be considered a crime.

Aiding and abetting a crime means to assist the perpetrator of a crime. A person aids and abets the commission of a crime when he or she (1) with the knowledge of the unlawful purpose of the perpetrator, (2) and with the intent or purpose of committing, facilitating, or encouraging commission of the crime, (3) by act or advice, aids, promotes, encourages, or instigates the commission of a crime.

An aider and abettor is one who is present at the crime scene and by word or deed gives encouragement to the perpetrator of the crime or by conduct makes clear that he or she is ready to assist the perpetrator when such assistance is needed. To aid and abet another to commit a crime, one must associate with the venture, act with the knowledge that an offense is to be committed, and share in the criminal intent of the perpetrator of the crime. It should be noted that a person may aid and abet without actively participating in an overt act.

In Politi v State Medical Board, the record showed that Barry J. Politi, MD, specifically limited the conduct of his assistant who was not properly registered as a physician’s assistant but was a registered nurse while working for Politi. There was no evidence that the assistant made any independent medical judgment or performed any medical procedures. The assistant’s conduct never exceeded the scope of practice for a nurse. Thus, the court ruled that the Ohio State Medical Board improperly imposed a penalty on Politi for assisting and abetting a nurse in the unauthorized practice of medicine.

In Siddiqui v Department of Professional Regulation, the court held that the purpose of the Illinois Medical Practice Act of 1987 is to protect the public health and welfare from those not qualified to practice medicine. Jawed Siddiqui, MD, was assisted by a trained and licensed pharmacist’s assistant. Siddiqui was charged with allowing the assistant to use his medical license as well as aiding the assistant in the unlicensed practice of medicine in violation of the Illinois Medical Practice Act. Specific acts performed by the assistant included the removal of sutures, the administration of injections, the diagnosis of diseases in patients, and the prescription of medications by signing Siddiqui’s name on prescription blanks.

Siddiqui argued that not every act performed by a physician constituted the practice of medicine. The court conceded that duties such as changing bandages, administering injections, and drawing blood are often performed by nonphysicians. However, the court found that diagnosing disease and making final decisions about the treatment of patients by prescribing medications, even by reissuing prior prescriptions, crossed the line into the practice of medicine. The fact that licensed professionals other than physicians could legally perform certain medical procedures under the supervision of a physician did not exempt the performance of those same procedures by an unsupervised and unlicensed individual from the scope of the Medical Practice Act.

Dr M’s assistants may be more valuable than any licensed health care professionals he has ever hired. Nevertheless, they are not licensed health care professionals. He may be found guilty of aiding and abetting a crime.

Newsletter

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to Dermatology Times for weekly updates on therapies, innovations, and real-world practice tips.